1. Introduction

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults (MIS-A) emerged as a significant post-infectious complication of COVID-19, initially identified in pediatric patients as MIS-C in 2020. The subsequent recognition of MIS-A in adults presented a new set of diagnostic challenges for clinicians. Characterized by systemic inflammation, fever, and potential organ involvement, MIS-A’s varied clinical presentation often mimics other severe conditions, making mis-diagnosis a critical concern. Distinguishing MIS-A from Kawasaki disease, sepsis, septic shock, and toxic shock syndrome is paramount, yet complex, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced diagnostic awareness.

The pathophysiology of MIS-A is still under investigation, but it is understood to involve a dysregulated immune response triggered by SARS-CoV-2. This aberrant immune reaction leads to systemic vasculitis and acute damage across multiple organs. Complement activation and the deposition of immunocomplexes in capillaries are also implicated in the disease process. The diagnostic journey for MIS-A is often complicated by its diverse symptomatology. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has established criteria for Mis-a Diagnosis, emphasizing severe illness requiring hospitalization and specific clinical and laboratory findings. A sustained fever is a primary symptom, alongside other clinical criteria, including cardiac involvement, mucocutaneous findings, neurological signs, shock, gastrointestinal issues, and thrombocytopenia. Adding to the complexity, laboratory evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and elevated inflammatory markers are essential for confirmation.

2. Case Report: Navigating Diagnostic Uncertainty in MIS-A

A 22-year-old previously healthy male presented to the infectious disease clinic with a three-day history of high fever (up to 40.2 °C), myalgia, arthralgia, headache, dry cough, dyspnea, and vomiting. His prior COVID-19 infection was mild, characterized by a subfebrile dry cough. Initial examinations revealed elevated neutrophils (93.2%), lymphopenia (3.30%), and thrombocytopenia (51 × 109/L). Upon admission, the patient was febrile (40.0 °C), tachycardic (129 bpm), and normotensive (104/70 mmHg). Lung ultrasound was unremarkable. Due to the non-specific presentation and fever of unknown origin, the patient was admitted for further investigation. A nasopharyngeal PCR test for COVID-19 was positive, with a high cycle threshold (Ct) of 33.54, indicative of a recent past infection rather than acute illness.

Initial laboratory results suggested a viral etiology, and symptomatic treatment was initiated. Extensive serological and blood culture investigations were undertaken to differentiate potential causes of the febrile state. Abdominal ultrasound showed mild splenomegaly. Despite initial management, the patient’s condition deteriorated over two days. Fever persisted, thrombocytopenia worsened, and inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP) increased (Table 1). Diarrhea and abdominal pain emerged, but stool microbiology was negative for infectious agents. Profound lymphopenia (CD4+ 0.10 × 109/L) prompted consideration of HIV infection, although this was later ruled out. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and opportunistic infection prophylaxis were empirically commenced due to the diagnostic uncertainty and risk of missing a treatable infection.

Over the subsequent two days, high fevers continued, accompanied by dyspnea, hypoxemia (SpO2 92%), hypotension, and tachycardia. A maculopapular rash, eyelid edema, and nonpurulent conjunctivitis developed. Repeat lung ultrasound revealed bilateral B-lines. ECG showed sinus tachycardia and ventricular extrasystoles. Laboratory findings indicated worsening thrombocytopenia (Figure 1), elevated inflammatory markers, troponin T, and NTproBNP (Table 1). Echocardiography, initially performed to investigate possible perimyocarditis, yielded no significant findings. However, due to escalating clinical deterioration, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a suspicion of MIS-A. At this stage, the clinical picture strongly suggested MIS-A, meeting both primary and secondary diagnostic criteria. Intravenous immunoglobulins and methylprednisolone were initiated. Antibiotic therapy was broadened to piperacillin/tazobactam and gentamicin to cover for possible septic shock, which remained in the differential diagnosis due to the severity of presentation and the initial diagnostic ambiguity.

Table 1.

Results of performed hematological and biochemical examinations (*—an unexamined parameter on that day).

| Day of Hospitalization | 1. | 3. | 5. | 6. | 8. | 13. | 17. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitored Parameter | |||||||

| C-reactive protein (CRP) (mg/L) | 82.06 | 128.1 | 172.2 | 115.1 | 63.6 | 8.2 | 0.69 |

| Procalcitonin (PCT) (ug/L) | 0.24 | 0.73 | 1.19 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) (ng/L) | 42.13 | 328.1 | 65.6 | 7.68 | 3.96 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.67 | 2.17 | 1.88 | 1.58 | 1.44 | 2.08 | 1.74 |

| Creatinekinase (ukat/L) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 1.2 |

| Creatine kinase-MB (ukat/L) | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| Troponin T (ug/L) | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.0121 | 0.077 | 0.041 | 0.028 | 0.005 |

| White blood cell (×109/L) | 6.36 | 3.26 | 4.80 | 7.21 | 9.55 | 7.26 | 8.79 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 82.6 | 82.1 | 91 | 91.7 | 93.2 | 89.2 | 77.9 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 101 | 64 | 51 | 67 | 105 | 273 | 267 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.43 | 1.5 | 1.48 | 2.26 | 2.40 | 1.96 | 0.46 |

| NTproBNP (ng/L) | 122 | * | 5438 | 8730 | 3709 | * | 125 |

Figure 1.

Platelet levels during hospitalization, illustrating the thrombocytopenia which contributed to the diagnostic complexity and initial mis-diagnosis concerns.

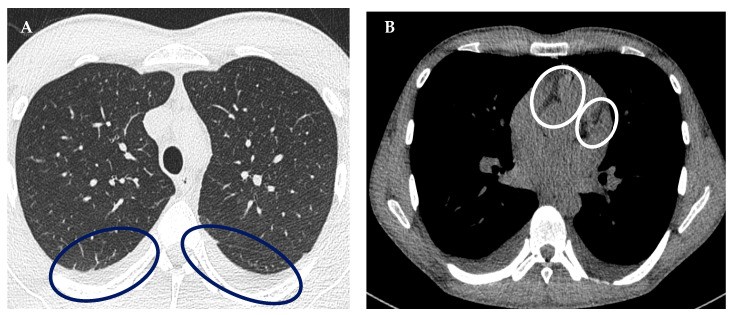

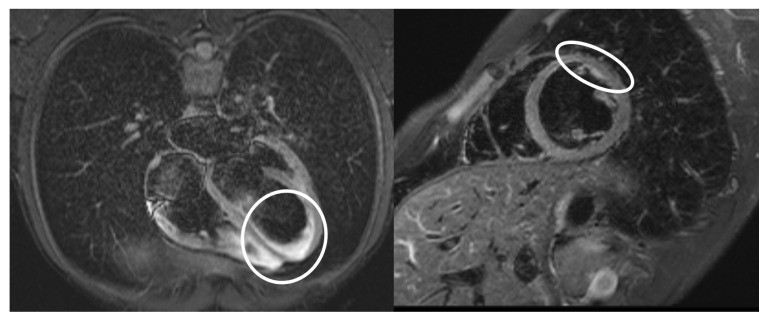

A chest HRCT revealed bilateral pleural effusions and fluidopericardium (Figure 2), further supporting cardiac involvement. Hematology and immunology consultations corroborated the MIS-A diagnosis and the ongoing treatment plan. Following the initiation of immunomodulatory therapy, the patient’s condition improved. Fever resolved, and inflammatory markers decreased (Figure 3). Given the clinical and laboratory response to MIS-A directed therapy and the absence of evidence for bacterial infection, antibiotics were discontinued. An internist recommended colchicine and bisoprolol for suspected myopericarditis and arranged for outpatient cardiac MRI. The patient was discharged after 22 days, continuing oral methylprednisolone, beta-blocker, and colchicine. Outpatient cardiac MRI confirmed residual inflammatory changes in the myocardium (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

HRCT of the chest revealing (A) bilateral fluidothorax and (B) fluidopericardium, key indicators that helped refine the mis-diagnosis suspicion toward MIS-A.

Figure 3.

Temperature curve throughout hospitalization, showing the initial persistent fever that contributed to the mis-diagnosis challenge and subsequent resolution with MIS-A treatment.

Figure 4.

Cardiac MRI highlighting the area of myocarditis (white circle), a crucial finding in confirming MIS-A and differentiating it from potential mis-diagnoses.

Table 2.

Results of performed microbiological examinations (*—repeated examination).

| Biological Material | Result |

|---|---|

| PCR SARS-CoV-2 | Nasopharyngeal Swab |

| Anti-Epstein-Barr virus antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Cytomegalovirus antibodies | serum |

| Anti-HIV virus antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibodies | serum |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | serum |

| anti-Hepatitis C antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Herpes simplex 1,2 antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Francisella tularensis antibodies | serum |

| Anti-Leptospira icterohemoragiae antibodies | serum |

| Candida/Aspergillus antigen | serum |

| antigen Legionella pneumophila/Streptococcus pneumoniae | urine |

| PCR Influenza A/B | nasopharyngeal swab |

| adeno, rota, noroviruses antigen | stool |

| stool/rectal swab culture | stool |

| urine culture | urine |

| Clostridioides difficile-toxin A/B, antigen | stool |

| blood culture | blood |

3. Discussion: The Diagnostic Labyrinth of MIS-A and Avoiding Misdiagnosis

MIS-A presents a significant diagnostic challenge due to its varied clinical presentation and overlap with other critical illnesses. The initial mis-diagnosis as a fever of unknown origin in our case highlights a common pitfall. The syndrome’s resemblance to conditions like sepsis, septic shock, and toxic shock syndrome necessitates a high index of suspicion, particularly in the context of recent COVID-19 infection. The interval between COVID-19 and MIS-A onset, typically 2–6 weeks, further complicates timely diagnosis, as the link to the prior infection may not be immediately apparent, leading to potential mis-diagnosis.

Patel et al.’s review of 221 MIS-A patients underscores the severity and diagnostic complexity of this condition. The study reported that common MIS-A symptoms include fever (96%), hypotension (60%), cardiac dysfunction (54%), dyspnea (52%), and diarrhea (52%). A significant proportion required ICU admission (57%) and respiratory support (47%). The overlap in symptoms with other severe conditions emphasizes the risk of mis-diagnosis and the need for careful differential diagnosis. Behzadi et al. also noted the predominance of fever and exanthema in MIS-A, further highlighting the non-specific nature of early symptoms that can contribute to mis-diagnosis.

In our case, the initial presentation with fever, headache, myalgia, and cough was non-specific, leading to a broad differential diagnosis. The subsequent development of conjunctivitis, rash, and elevated inflammatory markers, coupled with cardiac involvement, shifted the diagnostic consideration towards MIS-A. The transient gastrointestinal symptoms and rapid progression of extrapulmonary manifestations mimicked septic shock, reinforcing the initial mis-diagnosis concern. While DIC was considered in other severe MIS-A cases reported by Mazumder et al. and Kobe et al., it did not develop in our patient, further illustrating the variable clinical course and diagnostic challenges.

Based on the Brighton Collaboration criteria, our case met the definition for a definitive MIS-A diagnosis (Table 3). The cardiovascular involvement, as evidenced by tachycardia, hypotension, elevated troponin, and myocarditis on MRI, aligns with literature reports highlighting cardiac dysfunction as a frequent feature of MIS-A. Early recognition and rapid treatment initiation were crucial in preventing progression to shock and avoiding potential fatal outcomes from mis-diagnosis and delayed intervention. Cardiac MRI played a vital role in confirming myocarditis and excluding other causes of myocardial damage, aiding in the accurate diagnosis and preventing prolonged mis-diagnosis. The positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR at admission, while with a high Ct value, provided a critical link to recent infection, although serological testing for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies could have further strengthened the diagnostic certainty in cases where PCR is negative or the link to prior infection is less clear.

Table 3.

Diagnostic algorithm for the definitive case of MIS-A (12).

| Brighton Collaboration Case Definition | Patient from Our Case Report |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Age | 22 |

| Fever | |

| ≥3 Consecutive days | 6 |

| ≥2 Clinical features | |

| Mucocutaneous | Nonpurulent conjunctivitis, maculopapular exanthema on the chest |

| Gastrointestinal | Diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain |

| Shock/hypotension | Hypotension, clinical signs of shock |

| Neurologic | Headaches |

| Laboratory markers of inflammation | |

| Elevated CRP | 172.2 mg/L (maximal value) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 20 mm (after 1 h)/35 mm (after 2 h) |

| Elevated ferritin | 556 ug/L (maximal value) |

| Elevated procalcitonin | 1.19 ug/L (maximal value) |

| ≥2 Measures of disease activity | |

| Elevated BNP or NTproBNP or Troponin T | NTproBNP: 8730 ng/L; Troponin T: 0.121 ug/L (maximal value) |

| Neutrophilia, lymfophenia, or thrombocytopenia | Neutrophils: 93.2%; Lymphocyte 3.30%; Platelets 51 × 109/L |

| Echocardiographic evidence of cardiac involvement or physical sigmata of heart failure | Pericardial effusion |

| ECG changes consistent with myocarditis | Sinus tachycardia and bigeminal ventricular extrasystoles |

| SARS-CoV-2 | |

| Laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection or | Yes—PCR SARS-CoV-2 pozit. ct 32.2; ct 35.2 |

| Personal historyof suspected COVID-19 within 12 weeks or | Yes |

| Close contact with known COVID-19 case within 12 week | Probably yes |

| OR | |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination | Yes—1 dose before 1 year |

Treatment strategies for MIS-A, as reviewed by Kunal et al., commonly involve steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins. Our patient’s positive response to corticosteroids and immunoglobulins aligns with these findings, highlighting the effectiveness of immunomodulatory therapy in MIS-A. The initial use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, while ultimately not indicated for MIS-A itself, was a necessary measure in the context of diagnostic uncertainty and the need to rule out bacterial sepsis, a critical step in avoiding mis-diagnosis and ensuring patient safety.

4. Conclusions: The Imperative of Accurate Diagnosis in MIS-A

MIS-A remains a serious post-COVID-19 complication characterized by a dysregulated immune response and heterogeneous clinical manifestations, making accurate and timely diagnosis crucial. The risk of mis-diagnosis is substantial due to its clinical overlap with other severe conditions. Unrecognized and untreated MIS-A carries a high mortality rate, emphasizing the need for clinicians to maintain a high index of suspicion, particularly in patients with recent COVID-19 history presenting with fever and multisystem involvement.

Early diagnosis of MIS-A relies heavily on clinical assessment and patient history, as highlighted in this case where initial investigations were non-specific and misleading. Due to the potential for rapid deterioration and the dangers of mis-diagnosis, treatment should be initiated promptly based on clinical suspicion, without delaying for extensive microbiological or serological confirmation. The prognosis of MIS-A is significantly improved with early recognition and rapid implementation of immunomodulatory treatment, underscoring the importance of avoiding mis-diagnosis and ensuring timely intervention. This case underscores the importance of considering MIS-A in the differential diagnosis of adults presenting with fever, inflammation, and organ involvement following COVID-19, to mitigate the risks associated with mis-diagnosis and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This publication was created thanks to the support of the Operational Program Integrated Infrastructure for the project: “Analysis of the cardiovascular and immunological response of patients after overcoming COVID-19 with a focus on the research of new diagnostic markers and therapeutic agents”, code 313011AUB1.

Author Contributions

Data curation, O.Z. and Š.P.; formal analysis, O.Z. and A.R.; methodology, O.Z.; supervision, P.J.; validation, Š.P.; writing—original draft, O.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Louis Pasteur University Hospital (protocol code 69/EK/22, approval 6.5.2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.