Introduction

For many older adults, maintaining independence is paramount, and the prospect of long-term nursing home care is a significant concern. While factors predicting nursing home placement in community-dwelling elderly are relatively well-studied, less is understood about the acute events that often trigger such transitions. Hospitalization, in particular, can be a pivotal point, potentially leading to functional decline and subsequent long-term care needs. Indeed, a significant portion of individuals in long-term care facilities have experienced a recent hospitalization. This study delves into the crucial role of hospitalization as a precursor to long-term nursing home placement, highlighting that Most Institutionalized Long-term Care Patients Have A Diagnosis Of Dementia or other significant comorbidities that exacerbate their vulnerability following a hospital stay. We aim to quantify the percentage of long-term care nursing home admissions initiated by hospitalization, analyze trends over time, and identify key patient and healthcare system characteristics that elevate the risk of post-hospitalization institutionalization. Our central hypothesis posits that acute hospitalization often acts as the catalyst for long-term nursing home care, especially when interacting with pre-existing risk factors like dementia.

Methods

This research utilizes a retrospective cohort study design, leveraging a 5% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years and older from 1996 to 2008. Data was sourced from Medicare enrollment files, MEDPAR files, outpatient and carrier files, and provider of services files. The study population included patients admitted to acute care hospitals between January and April each year, alongside a non-hospitalized control group. To ensure focus on new nursing home placements, individuals with prior nursing home or skilled nursing facility (SNF) residence were excluded. The primary outcome measured was residence in a long-term care nursing home six months following hospital discharge (or a comparable date for controls). This was determined by identifying Evaluation and Management codes associated with nursing home care within a specific timeframe post-discharge, carefully excluding instances occurring during SNF stays. Statistical analyses, including chi-square tests and logistic regression, were employed to assess associations between various patient characteristics and the odds of nursing home placement.

Results

Our analysis revealed a stark contrast in nursing home placement rates between hospitalized and non-hospitalized individuals. Over the study period (1996-2008), 5.55% of patients were residing in a nursing home six months after hospitalization, compared to only 0.54% of the non-hospitalized control group. This tenfold difference underscores the profound impact of hospitalization on subsequent long-term care. Notably, approximately three-quarters of new nursing home placements were preceded by a hospitalization, highlighting its role as a major instigating event.

Several independent risk factors significantly increased the likelihood of long-term care placement after hospitalization. Advanced age was a prominent factor, with patients aged 85-94 years exhibiting 3.56 times higher odds of placement compared to those aged 66-74. Female gender also presented a heightened risk (OR = 1.41). Crucially, a pre-existing diagnosis of dementia emerged as a powerful predictor, increasing the odds of nursing home placement by 6.15 times. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) post-hospitalization carried the highest risk, with odds of 10.83. Conversely, having a primary care physician (PCP) was associated with a reduced risk (OR = 0.75).

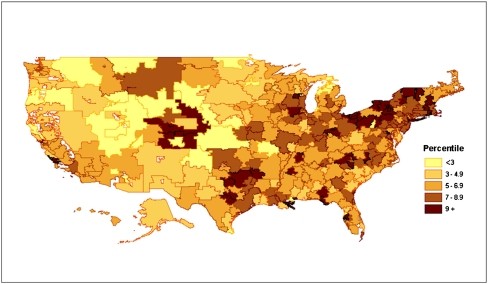

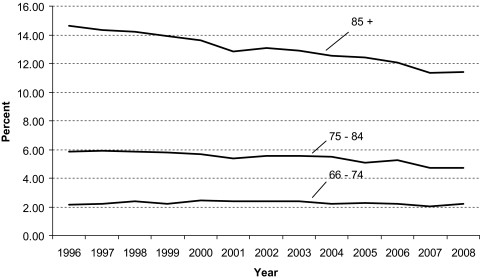

Interestingly, adjusted analyses indicated a gradual decrease in the risk of institutionalization after hospitalization over time, declining by 4% annually from 1996 to 2008. However, substantial geographic variations persisted, with rates of long-term care after hospitalization ranging widely across hospital referral regions, from below 2% to exceeding 13% for patients over 75 years in 2007-2008.

Table 1 further details the percentage of patients residing in nursing homes six months post-hospitalization, stratified by various characteristics. It reinforces the strong association between dementia and nursing home placement, with 23.74% of hospitalized patients with dementia residing in nursing homes compared to only 3.11% without dementia.

Table 1. Percentage of Patients Living in a Nursing Home 6 Months After Hospitalization Compared With Patients Not Hospitalized in a 5% Medicare Sample, 1996–2008

| Category | Hospitalized[*] | Nonhospitalized[*] |

|---|---|---|

| Number in Sample | Percent in Nursing Home | |

| Entire sample | 1,149,568 | 5.55% |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 66–74 | 447,978 | 2.26 |

| 75–84 | 496,483 | 5.45 |

| 85–94 | 191,883 | 12.48 |

| 95+ | 13,224 | 19.91 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 468,502 | 4.01 |

| Female | 681,066 | 6.60 |

| Race group | ||

| White | 1,007,770 | 5.48 |

| Black | 93,581 | 6.68 |

| Other | 48,217 | 4.81 |

| Had primary care physician in year prior | ||

| No | 498,651 | 6.33 |

| Yes | 650,917 | 4.94 |

| Dementia (prior and current) | ||

| No | 1,014,027 | 3.11 |

| Yes | 135,541 | 23.74 |

| Delirium (prior and current) | ||

| No | 1,132,974 | 5.40 |

| Yes | 16,594 | 15.13 |

| Incontinence (prior and current) | ||

| No | 1,107,032 | 5.31 |

| Yes | 42,536 | 11.59 |

| Other comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 481,633 | 4.48 |

| 1 | 305,544 | 5.05 |

| 2 | 171,742 | 6.43 |

| 3 or more | 190,649 | 8.24 |

| Region | ||

| New England | 57,429 | 7.18 |

| Middle Atlantic | 163,573 | 6.71 |

| East North Central | 203,366 | 6.23 |

| West South Central | 91,833 | 5.29 |

| South Atlantic | 247,029 | 5.05 |

| East South Central | 94,416 | 5.36 |

| West South Central | 128,670 | 5.21 |

| Mountain | 54,711 | 3.77 |

| Pacific | 98,746 | 4.78 |

| Admission year | ||

| 1996 | 88,155 | 5.61 |

| 1997 | 88,168 | 5.73 |

| 1998 | 87,477 | 5.87 |

| 1999 | 87,310 | 5.77 |

| 2000 | 85,805 | 5.80 |

| 2001 | 88,234 | 5.53 |

| 2002 | 91,745 | 5.66 |

| 2003 | 90,693 | 5.61 |

| 2004 | 93,023 | 5.52 |

| 2005 | 92,671 | 5.36 |

| 2006 | 89,534 | 5.46 |

| 2007 | 84,242 | 5.00 |

| 2008 | 82,511 | 5.15 |

* Notes: All differences in percentages between the hospitalized vs. nonhospitalized patients and all differences in percentages between categories within the hospitalized and nonhospitalized groups (eg, age categories, gender, etc.) were significant by chi-square with p > .0001.

Multivariable analysis further elucidated the risk factors. As shown in Table 2, after adjusting for various factors, dementia remained a highly significant predictor of nursing home placement post-hospitalization (OR = 6.15, 95% CI = 6.04–6.26). Discharge to an SNF retained its strong association with increased risk (OR = 10.83, 95% CI = 10.60, 11.06).

Table 2. Logistic Regression Estimating Odds of Nursing Home Residence at 6 Months Following Hospitalization in a 5% Medicare Sample, 1996–2008

| Characteristics | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Year (each 1 year increase) | 0.96 | 0.96–0.96 |

| Age group | ||

| 66–74 | 1 | |

| 75–84 | 1.86 | 1.82–1.91 |

| 85–94 | 3.56 | 3.47–3.65 |

| 95+ | 5.58 | 5.30–5.88 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | |

| Female | 1.41 | 1.38–1.43 |

| Race group | ||

| White | 1 | |

| Black | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 |

| Other | 0.96 | 0.92–1.01 |

| Has primary care physician | 0.75 | 0.74–0.77 |

| Dementia | 6.15 | 6.04–6.26 |

| Incontinence | 1.50 | 1.45–1.56 |

| Delirium | 1.39 | 1.33–1.46 |

| Other comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1.16 | 1.13–1.18 |

| 2 | 1.43 | 1.39–1.47 |

| 3+ | 1.92 | 1.87–1.96 |

| Region | ||

| Mountain | 1 | |

| New England | 1.62 | 1.53–1.72 |

| Middle Atlantic | 1.56 | 1.48–1.64 |

| East North Central | 1.56 | 1.48–1.64 |

| West North Central | 1.48 | 1.40–1.56 |

| South Atlantic | 1.23 | 1.17–1.30 |

| East South Central | 1.27 | 1.20–1.34 |

| West South Central | 1.25 | 1.19–1.32 |

| Pacific | 1.14 | 1.08–1.21 |

| Diagnosis related group | ||

| Circulatory | 1 | |

| Central nervous system | 2.23 | 2.17–2.30 |

| Respiratory | 1.33 | 1.29–1.37 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.07 | 1.04–1.11 |

| Musculoskeletal | 1.92 | 1.86–1.98 |

| Endocrine | 1.78 | 1.72–1.84 |

| Other | 1.83 | 1.78–1.88 |

| Emergency admission | 1.46 | 1.44–1.49 |

| Metropolitan area size (thousands) | ||

| 1 | ||

| 100–249 | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 |

| 250–999 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 |

| ≥1,000 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 |

| Hospital teaching status | ||

| Nonteaching | 1 | |

| Major | 0.88 | 0.86–0.90 |

| Minor | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 |

| Hospital type | ||

| For profit | 1 | |

| Nonprofit | 0.98 | 0.95–1.00 |

| Government | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 |

| Hospital size (beds) | ||

| 500+ | 1 | |

| 1.19 | 1.16–1.23 | |

| 200–349 | 1.07 | 1.04–1.10 |

| 350–499 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 |

* Note: OR = odds ratio.

Geographic variations in nursing home placement rates are visualized in Figure 1, highlighting regional disparities across the US. Figure 2 illustrates the trend of declining institutionalization rates over time, particularly pronounced in the oldest age groups.

Percentage of beneficiaries 75 years and older in a nursing home 6 months after hospitalization across health referral regions, 5% Medicare sample, 2007–2008. Alt text: Geographic map of the United States showing variations in nursing home placement rates after hospitalization for Medicare beneficiaries aged 75 and older. Regions are color-coded to represent percentage ranges, from less than 2% (lightest shade) to over 13% (darkest shade), illustrating significant regional disparities with lower rates generally in the Western states and higher rates in areas like Johnson City, TN and Temple, TX.

Percentage of beneficiaries living in a nursing home 6 months after hospitalization, by age of patient and year of hospitalization. Alt text: Line graph depicting the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes 6 months post-hospitalization, categorized by age group (65-74, 75-84, 85-94, 95+) and year of hospitalization (1996-2008). The graph demonstrates a clear downward trend in institutionalization rates over time for older age groups, particularly those 85 and older, while rates for the 65-74 age group remain relatively stable.

Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence for the significant role of hospitalization in precipitating long-term nursing home placement among older adults. A striking 75% of new nursing home admissions are preceded by a recent hospitalization, underscoring the hospital stay as a critical juncture in the pathway to long-term care. Our findings robustly highlight that dementia is a leading risk factor, confirming that most institutionalized long-term care patients have a diagnosis of dementia, or are highly vulnerable due to similar cognitive impairments and comorbidities.

The observed decrease in institutionalization risk over time, particularly in the oldest age groups, may reflect the growth of community-based alternatives to nursing homes, such as assisted living facilities. However, the increasing age of the Medicare population has mitigated the overall decline in unadjusted institutionalization rates. The changing trajectory of care, with a growing proportion of patients being discharged to SNFs before long-term care, also warrants attention. Discharge to an SNF emerged as the strongest predictor of subsequent long-term care, suggesting that SNF stays often serve as a transitional step towards permanent institutionalization.

The substantial geographic variations in nursing home placement rates raise questions about the preventability of many such admissions. It is unlikely that underlying risk factors alone account for such wide regional disparities. This suggests potential for targeted interventions to reduce avoidable long-term institutionalization, drawing parallels to efforts to reduce ambulatory-sensitive hospitalizations.

Several pathways may explain the link between hospitalization and long-term care. Acute events leading to hospitalization, such as stroke or myocardial infarction, can cause irreversible functional decline. Hospitalization itself can contribute to deconditioning and loss of independence. Furthermore, the increasing reliance on SNFs post-discharge may inadvertently facilitate transitions to long-term nursing home care.

The protective effect of having a primary care physician highlights the importance of continuity of care and physician involvement in care transitions. PCPs can play a crucial role in guiding patients and families through complex long-term care decisions. The declining availability of PCPs and their involvement in post-hospital care is a concerning trend that may contribute to less optimal care choices, including nursing home placement.

This study acknowledges limitations, including its focus on Medicare beneficiaries and the use of administrative data, which lacks information on social support, functional status, and patient preferences. Future research should explore these factors and investigate the role of rehospitalization and survival after nursing home admission.

Despite these limitations, our findings have significant implications for efforts to reduce long-term institutionalization. Targeting interventions during hospitalization and SNF stays, particularly for high-risk populations such as those with dementia, is crucial. Medicare data can be utilized to assess SNF performance in facilitating community discharge and to identify best practices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hospitalization is a major precursor to long-term nursing home placement, with the majority of new admissions being preceded by a hospital stay. A diagnosis of dementia significantly elevates the risk of institutionalization, suggesting that many long-term care residents are managing dementia. The pathway to long-term care increasingly involves discharge to an SNF. Interventions aimed at reducing long-term care utilization should focus on older adults during hospitalization and SNF transitions, with a particular emphasis on patients with dementia and strategies to mitigate functional decline and support community-based care options. Further research is needed to refine these interventions and address the geographic variations in institutionalization rates to ensure equitable and optimal care for all older adults.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AG033134, K05 CA134923, and P30 AG024832).

References

[1] Kane RA, Ouslander JG, Abrass IB. Essentials of clinical geriatrics. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

[2] Fried LP, Hadley EC, Walston JD, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–M157.

[3] Hughes CP, Cott CA, Hunter SW, Classen S, Naglie G. Older adults’ views on continuing to drive with cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Gerontologist. 2016;56(3):409–421.

[4] Molloy DW, Standish T, Parascandalo N, et al. What factors predict nursing home admission in community dwelling seniors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(1):1–12.

[5] Wolinsky FD, Johnson RJ. The use of health services by older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1991;46(4):S193–S206.

[6] Palmore EB. Predictors of longevity in men: a 25-year follow-up. Gerontologist. 1969;9(4 Pt 1):247–250.

[7] Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K, Papsidero JA. A prospective study of functional status among community elders. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(3):266–268.

[8] Glass TA, de Leon CM, Marottoli RA, Berkman LF. Population-based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. BMJ. 1999;319(7215):478–483.

[9] Kempen GI, Suurmeijer TP, de Haan RJ, Bouts RJ, Zitman FG. Risk factors for institutionalization of community-dwelling elderly people: a systematic literature review. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(1):10–19.

[10] McCusker J, Verdon J, Tousignant P, de Courval FP, Dendukuri N, Belzile E. Risk factors for hospital readmission among elderly patients: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):59–70.

[11] Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably playing golf last week.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793.

[12] Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. The relationship between intervening hospitalizations and transitions between frailty states. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(12):1337–1340.

[13] Bartels SJ, Moak GS, Fisher JE. Geriatric mental health services in rural areas: barriers and opportunities. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(10):1079–1085.

[14] Murtaugh CM, Freiman MP, Sekscenski ES, Laderman S, Fishman PA. Changes in the health care delivery system and postacute care in the 1990s. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(3):38–51.

[15] Mor V, Intrator O, Fries BE. The relationship between short-term and long-term residents in US nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(4):164–176.

[16] Liu CF, Rahman M, Mukamel DB, Temkin-Greener H. Nursing home admission after hospitalization: does hospital ownership matter? Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):651–660.

[17] Thomas JW, Holloway JJ, Peterson JC, et al. Outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries receiving different intensity levels of home health care after discharge from the hospital. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(5 Pt 1):1211–1233.

[18] Mukamel DB, Temkin-Greener H, Delavan R, Peterson D, Bajorska A, Stuart B. The transition from hospital to home health care and early rehospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(16):1753–1759.

[19] Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

[20] Landon BE, Wilson IB, McWilliams JM. Measuring physician performance with claims data. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):795–804.

[21] Wennberg JE, Cooper MM, editors. The Dartmouth atlas of health care 1999. Chicago: American Hospital Association Press; 1999.

[22] Billings J, Teicholz N. Uninsured patients in district of Columbia hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 1990;9(4):158–171.

[23] Epstein AM, Stern RS, Weissman JS. Do the poor cost more? A study of patients in a university hospital outpatient department. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(16):1123–1128.

[24] Boult C, Boult L, Murphy C, et al. A controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and community-based care for frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(8):855–862.

[25] Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Arling G, Meredith MP. Geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):262–270.

[26] Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620.

[27] Kane RL. Interventions to improve long-term care decisions. Gerontologist. 2010;50(3):285–293.

[28] Mechanic D. Discontinuity in care and the limits of integration. Milbank Q. 2009;87(4):709–730.

[29] Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Primary care physician supply and Medicare beneficiaries’ unmet needs, use of preventable services, and mortality. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):203–211.

[30] National Center for Health Statistics. Nursing home care in the United States: 2005 National Nursing Home Survey. Vital Health Stat 13. 2009;(167):1–199.

[31] Kasper JD, Shore AD, Penninx BW, et al. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and functional decline: the disability paradox. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2061–2068.

[32] Fried TR, Gillick MR. Medical decision making in advanced illness: the role of patient prognosis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(5):597–602.

[33] Werner C, Hoffman R, Nitsch D, et al. Predictors of mortality in older adults admitted to long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(4):235–244.