Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) represent a diverse group of malignancies characterized by their capacity to secrete bioactive peptides, potentially leading to symptoms such as flushing and diarrhea. Once considered rare, recent studies indicate a significant rise in NET incidence. In Canada, for instance, the incidence nearly doubled between 1994 and 2009, reaching a level comparable to cervical cancer. The subtle and often non-specific nature of NET presentations frequently results in diagnostic delays. Global surveys reveal an average delay of 52 months from symptom onset to diagnosis, with patients consulting multiple healthcare professionals before receiving an accurate assessment. This delay is particularly concerning as a considerable proportion of patients present with metastases at the time of initial Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis, classification, presentation, and diagnostic procedures. By summarizing key aspects of NETs, we seek to equip healthcare professionals with the knowledge to facilitate earlier diagnosis and prompt referral to specialist centers. The diagnostic recommendations outlined here are based on expert consensus and are consistent with current Canadian guidelines, ensuring alignment with established best practices in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and management.

Understanding Neuroendocrine Tumors: What Are NETs?

Neuroendocrine tumors originate from neuroendocrine cells, which are distributed throughout the body. The most frequent sites of NET development are the gastrointestinal tract (approximately 48%), the lung (25%), and the pancreas (9%). However, NETs can arise in various other organs, including the breast, prostate, thymus, and skin. A defining characteristic of neuroendocrine cells is their ability to produce hormones like serotonin, which can trigger symptoms such as flushing and diarrhea. They also produce other proteins, such as chromogranin A, a valuable biomarker in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis. Furthermore, neuroendocrine tissues typically express somatostatin receptors on their cell surfaces, making somatostatin analogues useful tools for both diagnostic imaging and therapeutic interventions in NET management.

Classifying Neuroendocrine Tumors: Grade, Differentiation, and Stage in NET Diagnosis

The biological behavior of NETs is determined by three key clinicopathologic features: grade, differentiation, and stage. These factors are crucial for prognosis and treatment planning following neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Grade: Assessing Tumor Aggressiveness

Histologic grade is a primary indicator of a NET’s biological aggressiveness. Grading is primarily based on two factors: the Ki67 index, which measures the percentage of cancer cells positive for Ki67 (a marker of cell proliferation), and the mitotic rate, which counts mitoses per 10 high-power microscopic fields. The World Health Organization (WHO) grading system, endorsed by expert groups, is widely used. Accurate grading is paramount as it is a major determinant of prognosis. Data from the SEER Program demonstrates a significant difference in median survival based on grade: 124 months for grade 1, 64 months for grade 2, and only 10 months for grade 3 tumors. This highlights the importance of precise grading in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and prognosis.

Figure 1: Ki67 Staining in Neuroendocrine Tumor Pathology

Figure 1: Microscopic view of neuroendocrine tumor tissue stained for Ki67 protein, indicating cell proliferation rate. (A) Shows a Ki67 index of 20%, demonstrating actively dividing tumor cells.

Table 1: WHO Grading Systems for Neuroendocrine Tumors

[Insert Table 1 Image Here]

Table 1: World Health Organization (WHO) grading system for neuroendocrine tumors, differentiating between lung/thymus NETs and gastroenteropancreatic NETs based on proliferative rate and nomenclature.

Differentiation: Resemblance to Normal Cells

Differentiation describes how closely NET cells resemble normal cells from their tissue of origin. Well-differentiated cells are similar to normal cells, while poorly differentiated cells are not. Generally, low-grade tumors (grades 1 and 2) are well-differentiated, and high-grade tumors (grade 3) are poorly differentiated. Differentiation is a key factor considered alongside grade in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and prognosis.

Stage: Extent of Tumor Spread

Stage refers to the extent of tumor spread within the body. The TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) system is used for staging NETs, similar to other cancers. For clinical practicality, NETs can be classified as early stage (resectable) or advanced stage (locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic). Staging is crucial in determining treatment strategies after neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Nomenclature: Evolving Terminology in NET Diagnosis

Historically, the term “carcinoid” was used to describe certain NETs. However, “carcinoid” is now discouraged as it fails to reflect the malignant potential of many NETs and incorrectly suggests that all NETs cause carcinoid syndrome. The preferred terminology is “neuroendocrine tumor” for grade 1 and 2 tumors, and “neuroendocrine carcinoma” for grade 3 tumors. Using accurate nomenclature is important for clear communication and correct neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and classification.

Clinical Presentation of Neuroendocrine Tumors: Recognizing Symptoms for Early NET Diagnosis

NETs can be discovered incidentally or suspected based on clinical symptoms. Functioning NETs cause symptoms due to hormone secretion, while nonfunctioning NETs may not produce noticeable hormonal symptoms. Both types often present late with nonspecific symptoms that can mimic other conditions, leading to delays in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis. Common misdiagnoses include gastritis, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, and menopause. Recognizing the potential symptoms is crucial for prompting appropriate investigations and timely neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Table 2: Functional Neuroendocrine Tumor Syndromes

[Insert Table 2 Image Here]

Table 2: Functional neuroendocrine tumor syndromes, linking tumor location and hormone production to specific clinical syndromes and symptoms, aiding in differential neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Table 3: Presenting Symptoms of Neuroendocrine Tumors

[Insert Table 3 Image Here]

Table 3: Common presenting symptoms of neuroendocrine tumors, categorized by gastroenteropancreatic and bronchopulmonary origins, highlighting the varied clinical manifestations that can complicate neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Specific symptoms can suggest the location of a NET. Small intestinal NETs can cause fibrosis leading to abdominal pain from bowel obstruction or mesenteric ischemia. Bronchopulmonary NETs often present with central lesions causing bronchial obstruction, recurrent pneumonitis, cough, and hemoptysis. Bronchopulmonary NETs can also cause ectopic ACTH production, which should be considered in unexplained Cushing syndrome. Awareness of these location-specific symptoms is important for narrowing down the differential diagnosis in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Carcinoid Syndrome: A Specific Manifestation

Carcinoid syndrome, characterized by flushing, diarrhea, and valvular heart disease, occurs when NET-produced hormones reach systemic circulation, typically after liver metastases develop. Carcinoid syndrome is more common in gastrointestinal NETs than bronchopulmonary NETs. Hindgut tumors (distal colon and rectum) are usually hormonally silent and do not cause carcinoid syndrome. Valvular heart disease occurs in a significant proportion of carcinoid syndrome patients, often asymptomatically, emphasizing the need for screening echocardiography. Carcinoid crisis is a life-threatening acute exacerbation characterized by severe flushing, bronchospasm, and unstable blood pressure, which can be triggered by anesthesia or tumor manipulation. Pre-treatment with somatostatin analogues is crucial in such scenarios. Understanding carcinoid syndrome is a key aspect of neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis, particularly in patients presenting with related symptoms.

Diagnostic Approaches for Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis

Accurate neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving medical oncologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and pathologists. Pathology, hormonal testing, and imaging are integrated to form a comprehensive diagnostic picture.

Pathology: Essential for Confirmation

Tissue biopsy is mandatory for neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis. Core needle biopsy is preferred over fine needle aspiration when surgery is not feasible, allowing for detailed assessment of tumor architecture, grade, and differentiation. Pathological examination is the gold standard for confirming neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

Syndrome-Specific Biochemical Testing: Identifying Functional NETs

For patients with symptoms suggestive of a functional NET, biochemical testing should target the specific syndrome. For suspected carcinoid syndrome or small intestinal mass, a 24-hour urine 5-HIAA test is recommended, although it has moderate sensitivity. Patients must avoid serotonin-rich foods before this test to prevent false positives. These syndrome-specific tests play a crucial role in the initial steps of neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis, especially in functioning tumors.

Nonsyndrome-Specific Biochemical Testing: Chromogranin A as a Key Biomarker

Chromogranin A (CgA) is a primary diagnostic biomarker for NETs, with high sensitivity but lower specificity. Elevated CgA levels can also be caused by proton-pump inhibitors, renal insufficiency, adenocarcinomas, and hypertension. Despite its limitations in specificity, CgA is a valuable tool in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and monitoring.

Diagnostic Imaging: Visualizing NETs

Two main types of diagnostic imaging are used in combination for neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis:

-

Cross-sectional Imaging (CT/MRI): CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are recommended for staging in all suspected NET cases. MRI of the liver or pancreas may be used for further clarification. These standard imaging techniques are essential for anatomical assessment in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

-

Functional Imaging (Somatostatin Receptor Scintigraphy and PET/CT): Functional imaging leverages the somatostatin receptor expression on NET cells.

- 111In-labelled pentetreotide scintigraphy: This is a commonly used radiotracer in Canada. It has variable sensitivity depending on the NET location.

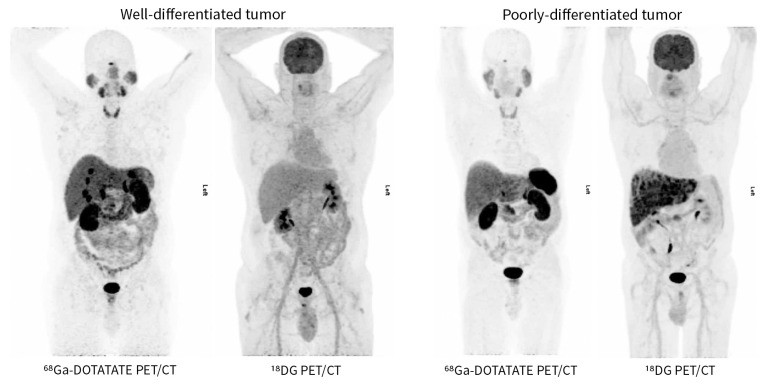

- 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT: A newer, more sensitive radioisotope imaging technique. Studies show significantly higher sensitivity compared to 111In-pentetreotide. Although currently limited to specialized centers, 68Ga-based imaging is becoming more accessible and is a significant advancement in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and staging.

It’s important to note that somatostatin analogue-based imaging is less effective for poorly differentiated tumors, which often lack somatostatin receptors. In these cases, 18FDG PET/CT, which detects tumors based on glucose uptake, is more sensitive.

Figure 2: Comparing 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and 18FDG PET/CT in NET Diagnosis

Comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and 18FDG PET/CT for Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis

Comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and 18FDG PET/CT for Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis

Figure 2: Comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and 18FDG PET/CT imaging for neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis, illustrating the differential sensitivity based on tumor differentiation. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT excels in well-differentiated tumors, while 18FDG PET/CT is superior for poorly differentiated tumors.

Endoscopic Imaging: For Pancreatic NETs

Endoscopic ultrasonography is the most sensitive imaging modality for pancreatic NETs, particularly for tumors smaller than 2 cm and for localizing insulinomas. It is often used intraoperatively for insulinoma localization. Endoscopic imaging plays a specific role in neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis of pancreatic origin.

Treatment Strategies Following Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis

Treatment plans are individualized based on tumor site, stage, grade, differentiation, symptoms, and patient factors.

Localized Disease: Surgical Intervention

Surgery remains the only curative treatment for localized NETs. Margin-negative resection and adequate lymphadenectomy are crucial. Surgeons must carefully inspect for synchronous lesions during resection, especially in midgut NETs where multiple primary tumors are common.

Metastatic Disease: Management Options

For metastatic disease, treatment strategies vary:

- Observation: In select patients with low-volume, asymptomatic, nonfunctional metastatic disease, observation may be appropriate.

- Somatostatin Analogues (SSAs): SSAs are a cornerstone of NET treatment, used for symptom control and for their anti-proliferative effects, improving progression-free survival.

- Surgery: Surgical resection of the primary tumor, especially in the small bowel, can prevent obstruction and may improve survival. Cytoreductive surgery can improve symptom control in high-volume metastatic disease.

- Molecularly Targeted Biologic Therapy: Everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) and sunitinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) have shown progression-free survival benefits in gastrointestinal, lung, and pancreatic NETs.

- Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT): PRRT using 177Lu-DOTATATE has demonstrated improved progression-free survival in advanced NETs.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is generally reserved for poorly differentiated metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas, often extrapolated from small cell lung cancer treatment protocols.

Conclusion: Advancing Neuroendocrine Tumor Diagnosis for Improved Outcomes

The incidence and prevalence of neuroendocrine tumors are increasing, making timely and accurate neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis more critical than ever. Increased awareness among clinicians is essential to reduce diagnostic delays and ensure patients receive appropriate multidisciplinary care. With rapidly expanding treatment options, early and accurate neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis can lead to improved symptom control, better quality of life, and extended survival for many patients. Prompt recognition of symptoms, appropriate diagnostic investigations, and referral to specialist centers are key to optimizing outcomes in neuroendocrine tumor management.

KEY POINTS

- The incidence and prevalence of neuroendocrine tumors are rising.

- Most patients present with non-specific symptoms, leading to diagnostic delays.

- Early and accurate neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis is crucial for effective management.

- Advancements in diagnostic imaging and biomarkers are improving neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis.

- A multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimal neuroendocrine tumor diagnosis and treatment.

- Increased awareness and timely referral are key to improving patient outcomes in neuroendocrine tumor management.

Footnotes

Competing interests: (As per original article)

Contributors: (As per original article)

This article was solicited and has been peer reviewed.

References

(References as per original article – to be added if required, maintaining original numbering or renumbering sequentially)