1. Introduction

The landscape of intensive care has evolved significantly, with a growing number of patients requiring and surviving critical care interventions. In Spain alone, over 240,000 adults are admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) annually [1]. ICUs are vital for patients facing life-threatening conditions and organ dysfunction requiring specialized, continuous monitoring and treatment [2]. Crucially, over 90% of these patients survive their ICU stay [3], highlighting the importance of the transition from the ICU to the general ward. The COVID-19 pandemic has further underscored the critical role of ICUs in managing severely ill patients [4].

Discharge from the ICU represents a significant and often precarious transition point for patients. Moving from a highly specialized, technologically advanced environment to a general ward presents challenges and risks. This transition involves numerous healthcare professionals and necessitates seamless information exchange and responsibility transfer [5]. ICU discharge is not merely a logistical procedure; it profoundly impacts patients’ emotional and psychological well-being. Feelings of displacement, heightened anxiety, and a marked loss of autonomy are common experiences during this transition [6,7]. A significant aspect of this experience is powerlessness. Patients often report feeling powerless during ICU discharge, stemming from a lack of medical knowledge and a perceived loss of control over their own bodies and health journey [8]. This feeling of powerlessness can be a critical nursing diagnosis in critical care patients as they prepare for discharge.

The perception of powerlessness and the emotional distress associated with ICU discharge can significantly increase the risk of post-ICU syndrome (PICS). PICS encompasses a range of impairments, including mental and cognitive deficits, physical disabilities, and psychological issues like anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [9]. Effective interventions aimed at ICU survivors are paramount to mitigate negative outcomes and enhance their long-term quality of life. Needham and colleagues (2012) emphasized the importance of early psychological support, mobility programs, post-discharge follow-up, ICU diaries, therapeutic environments, functional reconciliation, and the ABCDEFGH bundle as key strategies to improve post-ICU outcomes [10,11]. Addressing powerlessness and ensuring a well-prepared ICU discharge process is, therefore, a cornerstone in reducing the risk of subsequent PICS.

Nurses, as integral members of the multidisciplinary ICU team, play a pivotal role in planning and executing the ICU transition. They are central to patient care interventions during this critical phase [12]. Assessing patient needs during transition and providing tailored information and education to both patients and their families falls squarely within the nursing domain. Recognizing the critical nature of the nurse’s role, some institutions have introduced specialized nursing positions like “liaison nurses” to enhance support during ICU discharge [13,14]. Furthermore, the expertise of ICU nurses in multidisciplinary program implementation during ICU transition has been recognized for its potential to reduce ICU readmission rates and overall hospital mortality [15].

Addressing patient powerlessness begins with nurses’ ability to recognize the signs and symptoms indicative of these feelings [16]. Empowerment, a multifaceted concept [17,18,19,20,21,22], aims to shift patients from a passive recipient role to active participants in their health decisions and overall well-being [20]. Successful patient empowerment enables individuals to reconcile their feelings of vulnerability and insecurity, fostering a sense of control over their health journey [8,23]. The benefits of enhanced patient empowerment are substantial, including reduced distress and strain, increased coherence and control, personal growth, and improved comfort and satisfaction [24].

Patient empowerment strategies offer a promising avenue for mitigating the stress associated with ICU discharge and addressing the nursing diagnosis of powerlessness. While empowerment strategies have been increasingly applied in chronic disease management like diabetes [25], cancer [26,27], and other clinical settings [28,29], their application in the context of ICU discharge, specifically to address powerlessness, remains less explored. Although patient empowerment is a multidisciplinary responsibility, nurses often take the lead in implementing these strategies during ICU transition [30,31].

This systematic review was undertaken to synthesize evidence on patient empowerment interventions during ICU discharge, pinpoint existing gaps in knowledge, and propose directions for future research and clinical practice. The primary goal was to evaluate the effectiveness of nursing interventions in enhancing patient empowerment for adult patients transitioning from the ICU, with a focus on alleviating feelings of powerlessness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, Protocol, and Registration

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines [32] (Supplementary Material File S1). The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42021254377 (Supplementary Material File S2).

2.2. Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion in the Review

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving adult patients of all genders undergoing ICU discharge were included. Studies were selected based on their evaluation of nursing empowerment interventions and their impact on patient well-being. Inclusion criteria were based on the PICO framework: Population (P): adults during ICU discharge; Intervention (I): patient empowerment interventions delivered by nurses; Comparison (C): usual care or no intervention; Outcome (O): physical and mental health symptoms, patient satisfaction, and readmission rates. Included studies featured at least one group receiving a nursing empowerment intervention and a control group receiving standard ICU discharge care. Nursing empowerment interventions were defined as information, behavioral guidance, and advice related to ICU discharge management provided through verbal, written, audio, or video formats. Studies focusing on adult populations during ICU discharge were considered.

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: (1) original research; (2) patient admission to the ICU; (3) reported impact of nursing intervention; (4) full text availability, without language restrictions. Studies involving patients under 18 years of age were excluded. Additionally, observational studies, editorials, letters to the editor, review articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, in vivo, and in vitro studies were excluded.

The primary outcome of interest was the range of nursing empowerment interventions designed for ICU discharge in adult survivors. Secondary outcomes included the effects of these nursing interventions on various patient parameters.

2.3. Search Strategies and Data Resources

A comprehensive search was conducted across six databases: Embase, PubMed/MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CUIDEN Plus, and LILACS. The search was performed on May 17, 2021, supplemented by a manual review of reference lists from included articles. Search terms (Table 1) were combined using Boolean operators (OR, AND, NOT). All identified references were managed using Rayyan software (http://rayyan.qcri.org accessed on July 10, 2021) [33]. To ensure thoroughness, a cited-reference search (“reverse search”) was conducted for each included article using Google Scholar, and all results were reviewed.

Table 1.

Terms of searching in the different databases and results obtained.

| Database and Keywords Combinations | Articles |

|---|---|

| PUBMED | |

| ((empowerment patient OR patient education OR patient information) AND (ICU discharge OR ICU transfer OR ICU transition) AND (nursing interventions) AND (adults)) | 214 |

| EMBASE | |

| ((empowerment AND patient OR patient) AND (education OR patient) AND information AND (”ICU discharge” OR (ICU AND (“discharge”/exp OR discharge)) OR “ICU transfer” OR (ICU AND (“transfer”/exp OR transfer)) OR ”ICU transition” OR (ICU AND (”transition”/exp OR transition))) AND (”nursing interventions” OR ((”nursing”/exp OR nursing) AND (”interventions”/exp OR interventions))) AND (”adults”/exp OR adults) | 27 |

| CINAHL | |

| ((empowerment patient OR patient education OR patient information) AND (ICU discharge OR ICU transfer OR ICU transition) AND (nursing interventions) AND (adults)) | 2 |

| Cochrane Library | |

| ((empowerment patient OR patient education OR patient information) AND (ICU discharge OR ICU transfer OR ICU transition) AND (nursing interventions) AND (adults)) | 30 |

| CUIDEN Plus | |

| ((empowerment patient OR patient education OR patient information) AND (ICU discharge OR ICU transfer OR ICU transition) AND (nursing interventions) AND (adults)) | 1 |

| LILACS | |

| ((empowerment patient OR patient education OR patient information) AND (ICU discharge OR ICU transfer OR ICU transition) AND (nursing interventions) AND (adults)) | 0 |

| TOTAL | 274 |

2.4. Review and Study Selection

Two reviewers (CC and RTC), experienced in literature reviews, independently conducted the review process. Initially, titles and abstracts of all retrieved references were screened (CC and RTC). Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were then retrieved and assessed against the predefined inclusion criteria (CC and RTC). Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Studies not meeting the criteria were excluded, and their bibliographic details and reasons for exclusion were documented.

2.5. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors (CC and RTC) using standardized protocols and reporting forms. Extracted information included study design, population characteristics, nursing intervention details, and key results. When necessary, supplementary data or author contact was used to obtain missing information.

Due to heterogeneity in outcome measures, a narrative synthesis approach was employed. Each study was summarized focusing on participant characteristics, intervention details, instruments used, and critical outcomes. This synthesis was reviewed by another author (RTC). A summary table was created (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the studies included.

| Author, Year, Country | Population | Groups (n) | Intervention | Instrument * | Findings/Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bench2015UK | 158 patients (aged >18 years) in two ICUs in England. | CG 1 (59)CG 2 (48)EG (51) | There were three groups; EG received UCCDIP, comprising two booklets, one for the patient with a personalized discharge summary, and one for the family, given prior to discharge to the ward. CG 1 received the usual information and CG 2 received the booklet produced by the ICU steps. | HADSBCOPEPEI | There were no significant differences in psychological well-being measured using HADS, assessed at 5 ± 1 days post unit discharge and at 28 days/hospital discharge among the 3 groups. There were no differences in the other scales after intervention. |

| Kleinpell2004USA | 100 patients (aged 65–95 years) in two ICUs of two Midwestern University medical centers. | CG (53)EG (47) | A DPQ was performed to assess discharge needs and define an early discharge planning nurse intervention with formal structured communication to the discharge planning nurse when the patient was transferred from the ICU. | Discharge Adequacy Rating FormSF-36 | Patients in the EG were more ready for discharge, more likely to report they had adequate information, and less concerned about managing their care at home than patients in the CG. They also better understood their medicines and danger signals indicating potential complications. |

| Knowles2009UK | 36 patients (aged 18–85 years) discharged to medical/surgical wards at Royal Bolton Hospital, Lancashire. | CG (18)EG (18) | ICU diary, containing daily information about their physical condition, procedures and treatments, events occurring on the unit, and significant events from outside the unit. | HADS | Patients in the EG displayed significant decreases in both anxiety and depression compared to CG. |

| Kuchi2020Iran | 84 patients (18–65 years of age) with coronary artery disease admitted to post-CCU wards in Tehran hospital. | CG (42)EG (42) | An information and education-based empowerment program following five stages:1. Motivating patient self-awareness.2. Assessing causes of problems.3. Setting goals.4. Developing personal self-care plans.5. Assessing achievement of goals. | SAQPerception of Risk of Heart Disease Scale. | There were significant differences between the two groups in total score of perceived risk and its subscales. The intervention changed patients’ attitudes toward risk-motivating behavior change and improving physical health. |

| Wade2019UK | 1458 patients (>18 years of age) in 24 general ICUs in UK | CG (789)EG (669) | Nurse-led preventive psychological intervention for critically ill patients, comprising three phases:1. Creating a therapeutic environment in ICU.2. Three stress support sessions for patients screened as acutely stressed.3. Relaxation and recovery program for patients screened as acutely stressed. | PTSD Symptom Scale–Self-Report.STAI-6.HrQoL | There were no significant differences in PTSD symptom severity at 6 months among groups. There were no differences in the other scales after intervention. |

| Ramsay2016UK | 240 patients (>18 years of age) in Edinburgh, Scotland | CG (120)EG (120) | A complex intervention aimed towards post-ICU rehabilitation delivered between ICU and hospital discharge by dedicated rehabilitation assistants (RAs) working together with existing ward-based clinical teams. The intervention comprised:enhanced physiotherapynutritional careinformation provisioncase-management | PEQHRQoLSF-12HADSDavidson’s Trauma Scale | The PEQ revealed significant differences between groups, suggesting greater patient satisfaction in the EG. Focus group data strongly supported and helped to explain these findings. There were no differences in the other scales after intervention. |

| Demircelik2015Turkey | 100 patients, Turkish coronary ICU | CG (50)EG (50) | Multimedia nursing educational intervention. | HADS | There were significantly higher decreases in HADS scores in the EG. |

| Bloom2019USA | 232 patients (≥18 years of age) at Vanderbilt University Hospital. | CG (121)EG (111) | Interdisciplinary ICU recovery program, comprising:inpatient visit by a nurse practitioneran informational pamphleta 24/7 phone number for the recovery teaman outpatient ICU recovery clinic visit with a critical care physician, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, psychologist, and case manager | Death and readmission rate | Hospital readmission after discharge at 7 days (3.6% vs. 11.6%) and 30 days (14.4% vs. 21.5%), median time to readmission (21.5 (IQR 11.5–26.2) vs. 7 (4–21.2) days) and the composite outcome of death or readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge (18% vs. 29.8%) were significantly better in the ICU recovery program group than in the usual care group. |

* Instrument used to assess the impact of the intervention. Abbreviations: BCOPE: Brief Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced, CG: Control group, DPQ: Discharge Planning Questionnaire, EG: Experimental group, HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score, HrQoL: Health-related Quality of Life, ICU: Intensive Critical Unit, ICU steps: Intensive care guide for patients and relatives, IQR: Interquartile range, SAQ: Seattle Angina Questionnaire. PEI: Patient Enablement Instrument; PEQ: patient experience questionnaire, PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, SF-12: Short Form 12 Health Survey, STAI-6: State Trait Anxiety Inventory 6-item version, UCCDIP: User-Centered Critical Care Discharge Information Program, UK: United Kingdom.

2.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [34] was used to independently assess the methodological quality of included studies by two reviewers (RTC and YT). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

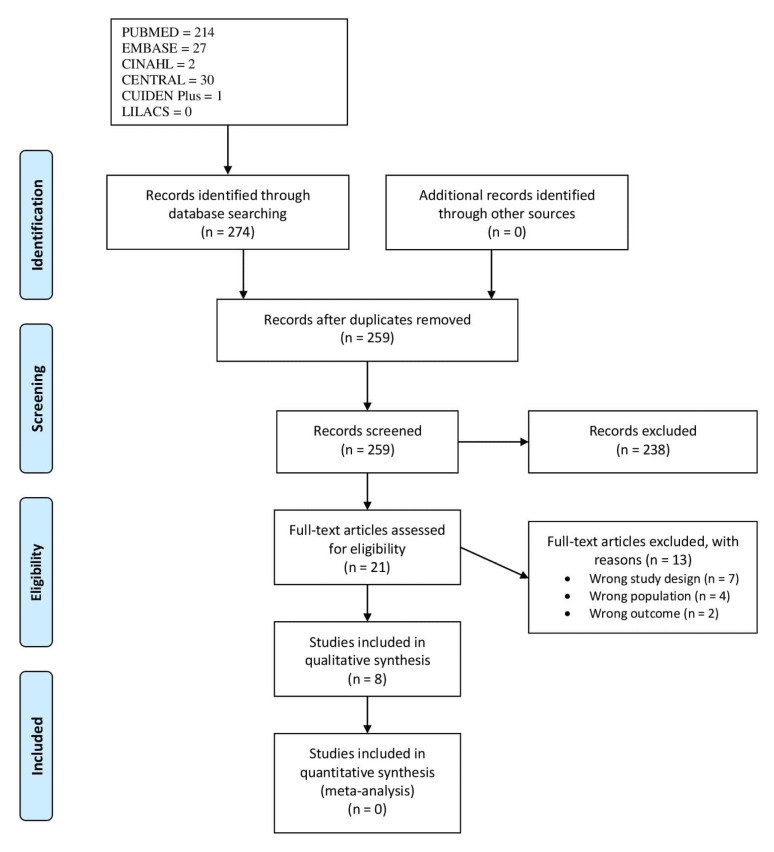

The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. The initial search yielded 274 references, which reduced to 259 after duplicate removal. Following title and abstract screening, 238 studies were excluded. Twenty-one full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, resulting in the exclusion of 13 due to study design (n = 7), population (n = 4), and outcome (n = 2) issues. Eight articles met the inclusion criteria [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. The reverse search did not identify any additional relevant references.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The included studies were conducted in various countries: four in England [35,37,39,42], two in the USA [36,41], one in Iran [38], and one in Turkey [40]. Detailed characteristics of each study, including design, sample, setting, interventions, and outcomes, are summarized in Table 2.

3.3. Participants

Across the eight included studies, a total of 2408 patients participated. Sample sizes ranged from 36 [37] to 1458 [39], with 1108 (46%) patients receiving the nursing intervention. The mean age of patients in the intervention groups ranged from 54.6 ± 7.9 [38] to 60.4 ± 15.0 [39] years. Patient characteristics are further detailed in Table 2.

3.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

The risk of bias varied across the included articles. Randomization methods and allocation concealment were generally adequate. Participant blinding was reported in one trial [37], and blinded outcome assessment was present in two studies [35,42]. However, most trials lacked blinding of participants, personnel, or outcome assessors (Figure 2). A considerable proportion of authors provided insufficient information to fully assess other potential sources of bias. The results of the quality assessment are visually represented in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment summary.

Figure 3.

Quality assessment of studies included.

3.5. Main Findings

3.5.1. Primary Outcome

The primary outcome, nursing interventions aimed at patient empowerment during ICU discharge, varied across studies. These interventions included:

- Information and Education Programs: Providing patients and families with verbal and written information, booklets, and multimedia resources about ICU discharge, medications, potential complications, and self-care strategies [35,37,38,40].

- Discharge Planning and Needs Assessment: Utilizing questionnaires and structured communication to assess individual patient needs and develop tailored discharge plans, often involving early discharge planning nurse interventions and formal communication with discharge planning nurses [36].

- ICU Diaries: Implementing ICU diaries containing daily updates on the patient’s condition, treatments, and events within and outside the ICU, aiming to improve emotional well-being and understanding of their ICU experience [37].

- Nurse-Led Recovery Programs: Implementing comprehensive, nurse-led programs involving inpatient visits by nurse practitioners, informational pamphlets, 24/7 phone support, and outpatient ICU recovery clinic visits with multidisciplinary teams [41].

- Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Programs: Complex interventions involving dedicated rehabilitation assistants working with ward-based teams to provide enhanced physiotherapy, nutritional care, information provision, and case management [42].

- Preventive Psychological Interventions: Nurse-led interventions comprising therapeutic environment creation in the ICU, stress support sessions, and relaxation and recovery programs for acutely stressed patients [39].

3.5.2. Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcomes, focusing on the effects of these nursing interventions, included:

- Psychological Well-being: Several studies assessed anxiety and depression using tools like the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Some interventions, like ICU diaries and multimedia education, showed significant reductions in anxiety and depression scores [37,40], while others, such as discharge information booklets and comprehensive nurse-led interventions, did not demonstrate significant improvements in these outcomes [35,39].

- Patient Satisfaction and Preparedness for Discharge: Interventions like discharge planning and complex rehabilitation programs showed improved patient satisfaction and a greater sense of preparedness for discharge [36,42].

- Hospital Readmission and Mortality: Interdisciplinary ICU recovery programs demonstrated significant reductions in hospital readmission rates and composite outcomes of death or readmission within 30 days of discharge [41].

- Perceived Risk and Health Behaviors: Information and education-based empowerment programs positively influenced patients’ perceived risk of heart disease and promoted health-motivating behavior changes [38].

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms: One study evaluating a nurse-led preventive psychological intervention found no significant difference in PTSD symptom severity at 6 months post-ICU discharge [39].

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to investigate nursing interventions focused on patient empowerment during ICU discharge and analyze their impact, particularly in addressing patient powerlessness. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review specifically examining empowerment interventions during this critical transition.

Existing literature highlights limitations in study design, sample sizes, and randomization in studies evaluating information and education for ICU patients during their stay and discharge [43]. However, patient empowerment studies in other healthcare domains have consistently shown that nursing interventions can effectively reduce patient stress, anxiety, and depression [44,45] (Figure 4). Addressing patients’ emotional states is crucial to determine the optimal timing, method, and setting for interventions, ensuring patients are emotionally prepared for the transition from the ICU to the general ward. A key aspect of patient empowerment in this phase is restoring situational control [21,23,46]. ICU admission often leads to feelings of lost control, especially for severely ill patients requiring sedation and mechanical ventilation, rendering them dependent and unable to make decisions. Adapting to this dependence and accepting procedures can exacerbate feelings of helplessness and powerlessness. Complications and prolonged recovery further delay transfer, intensifying these feelings. Meleis et al. (2000) emphasized that preparation and knowledge are crucial for empowerment during transitions, while a lack thereof can be a significant barrier [47]. Creating an environment that prioritizes restoring patient control and ensuring nurses facilitate knowledge acquisition tailored to patient expectations is therefore paramount [48,49].

Figure 4.

Main findings of patient empowerment strategies performed by nurses.

Information and education emerged as the primary intervention in half of the reviewed studies [37,38,40,50]. The significance of these elements is well-documented [7,43], with evidence suggesting that their absence impedes active patient participation during transitions [51].

Emotional well-being was assessed in four studies [35,37,38,40]. Knowles et al. (2009) demonstrated the benefits of ICU diaries in improving patient emotional states. Conversely, Bench and Day (2015) found no significant emotional benefit from written and verbal discharge information, possibly due to the intervention timing. Earlier intervention may yield more positive outcomes by providing patients with a more informed perspective earlier in the discharge process.

Other interventions focused on assessing patient needs through questionnaires and developing personalized recovery and discharge plans with targeted nursing interventions. Continuous assessment of patient needs throughout their ICU stay and transition is essential for creating dynamic care plans that ensure care continuity, despite the time investment required. Kleinpell et al. (2004) showed that such interventions improved patient preparedness for both ICU and hospital discharge.

Complex interventions addressing patient recovery have demonstrated greater patient satisfaction [42] and reduced ICU readmission and mortality rates [41]. However, Wade et al. (2019) found no association between nurse-led interventions and decreased PTSD post-ICU discharge [39]. Improving the evaluation and measurement of nursing intervention effectiveness is crucial to ascertain their true benefits and contribution to positive ICU discharge outcomes.

The role of advanced practice nurses in patient evaluation and follow-up during ICU discharge, often within multidisciplinary teams (nurse-led or case management), was highlighted in three studies [39,41,42]. While advanced practice nurses have been part of multidisciplinary teams for complex patient care for over two decades, their involvement in ICU discharge is a more recent development. These roles present opportunities to empower patients and families, facilitating their adjustment to life outside the ICU environment and mitigating feelings of powerlessness.

Interestingly, the term “patient empowerment” was not explicitly used in all included studies, although related concepts were investigated. This observation aligns with findings from a systematic review on empowerment in online communities [50]. This may reflect the multifaceted nature of empowerment and the need for researchers to broaden their perspectives beyond individual aspects to include structural dimensions of power [51]. Future research should focus on refining the conceptual and operational understanding of patient empowerment, integrating individual, interpersonal, and structural elements, and emphasizing patient autonomy and perceived self-efficacy [52].

This systematic review’s primary contribution is the identification of nursing interventions to enhance patient empowerment during ICU transition, directly addressing the nursing diagnosis of powerlessness. Future studies employing rigorous methodologies will strengthen the evidence base for these interventions, leading to improved patient outcomes and experiences during ICU discharge.

4.1. Applicability of the Findings to the Review Question

The interventions reviewed, primarily implemented by nurses, demonstrate the potential of nursing practice to address powerlessness and improve the ICU discharge transition. Informed and educated nurses are well-positioned to apply empowerment interventions effectively. Our findings underscore the impact of these interventions on patient empowerment during ICU discharge, carrying significant clinical implications. Routine assessment of anxiety and depression at ICU discharge is recommended to identify patients who would benefit from targeted interventions.

However, a deeper understanding and integration of the concept of patient empowerment are needed among ICU nurses to fully leverage its potential in practice. Recognizing that patient dependence and needs vary, nurses should avoid applying a uniform approach to all patients transitioning from the ICU. Individualized assessment of patient responses and expectations is crucial for tailoring care and promoting patient decision-making and preferences. Empowered and well-informed patients transitioning to the general ward can also facilitate smoother care provision by ward nurses [48].

4.2. Strengths of the Review

This systematic review benefits from a comprehensive literature search, including full-text publications without language restrictions. The rigorous review process, conducted by trained and experienced reviewers, enhances the reliability of the findings.

4.3. Limitations of the Review

A limitation is the search strategy, which focused on articles explicitly mentioning “patient empowerment” and “ICU discharge” in titles or abstracts. This may have excluded relevant studies that explored empowerment-related interventions using different terminology.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights various nursing interventions during ICU discharge that aim to empower patients and address feelings of powerlessness. These interventions encompass information provision, discharge needs assessment, nursing care plans, and advanced practice nurse follow-up. Information and education were the most frequently implemented interventions and were generally associated with improved patient control and reduced negative emotional effects.

Practice Implications

Nursing interventions grounded in patient empowerment hold promise for improving the ICU discharge experience and mitigating patient powerlessness. This review provides valuable insights for developing and implementing new nursing interventions in similar contexts. Identifying the most effective nursing interventions for patient empowerment in critical care and rigorously evaluating their impact on patient outcomes is crucial for future research and practice.

Future research should prioritize identifying the most effective methods for information delivery, education, and patient empowerment during ICU discharge. Further investigation into interventions that reduce negative post-transfer effects, such as structured teaching programs, is warranted. Qualitative research exploring the lived experience of ICU discharge from the patient perspective is also essential to inform the development of truly patient-centered empowerment strategies. Combining qualitative and quantitative measures will provide a more comprehensive evaluation of nursing intervention effectiveness on patient outcomes during this vulnerable transition.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph182111049/s1, File S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews; PRISMA checklist, File S2: Systematic review registration: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021254377.

Click here for additional data file. (119.2KB, zip)

Author Contributions

C.C. and R.T.-C.: responsible for the protocol, conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, reviewing procedure and data extraction, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Y.T.: reviewing procedure and data extraction, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. P.C.: resolve disagreements between C.C. and R.T.-C., conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. I.M. and P.M.-R.: formal analysis, methodology, writing—review and editing. M.R.-G., M.A.M.-M.: writing—review and editing. G.M.-E.: funding acquisition. P.D.-H. and P.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors provided critical revision of the protocol and final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nursing and Society Foundation as part of the Nurse Research Projects Grants; grant number PR-248/2017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as we only reviewed published studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Click here for additional data file. (119.2KB, zip)