Introduction

The opioid crisis continues to be a significant public health concern, with opioid-related deaths and hospitalizations remaining alarmingly high. Prescription opioids, while necessary for pain management in some cases, contribute substantially to this crisis. Even short-term opioid prescriptions can increase the risk of long-term use and the development of opioid use disorder (OUD). OUD, as defined by the DSM-5, is a complex condition, and its evolving definition and varied research approaches make estimating the risk of OUD after opioid prescription challenging. Recognizing the severity of the issue, healthcare systems are implementing strategies to combat OUD, including national guidelines and the removal of barriers to treatment medications like methadone. This article focuses on simplifying the diagnosis and management of OUD within primary care settings, drawing upon evidence-based recommendations to support clinicians in providing effective care. This simplified approach aims to empower primary care practitioners and facilitate shared decision-making with patients, ultimately improving outcomes in OUD management.

Methods

This guideline was developed by a committee of thirteen healthcare professionals representing diverse primary care settings and specialties across Canada. The committee followed a rigorous methodology based on the Institute of Medicine’s principles for trustworthy clinical practice guidelines. Key questions regarding OUD management in primary care were formulated through an iterative process. These questions encompassed critical areas such as:

- The effectiveness of managing OUD in primary care settings.

- Diagnostic approaches for OUD.

- Pharmacotherapy options, including buprenorphine-naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and cannabinoids.

- Prescribing practices like witnessed ingestion, urine drug testing, and treatment agreements.

- Strategies for tapering opioid therapy, including opioid agonist therapy (OAT).

- The role of psychosocial interventions.

- The utility of residential treatment programs.

- Management of co-occurring conditions such as pain, ADHD, anxiety, and insomnia in patients with OUD.

A dedicated team of evidence evaluation experts conducted systematic reviews to address each key question. This involved reviewing existing systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Observational studies were considered when higher-level evidence was lacking. The search included major databases like MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and Google, alongside reviews of published guidelines and reference lists. The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology was used to translate the evidence into practice recommendations, which were then refined through committee consensus and peer review by a broad range of healthcare professionals and individuals with lived experience. Strong recommendations are indicated by “we recommend,” while weaker recommendations are prefaced with “could consider.”

Evidence Limitations

It’s important to acknowledge several limitations within the existing body of evidence on OUD. Inconsistent terminology in defining OUD (e.g., “heroin abuse,” “opioid use,” “addiction”) and control groups (e.g., “usual care”) makes comparisons across studies challenging. Many studies focused on heroin users in treatment settings, potentially limiting generalizability to prescription opioid users in primary care. Outcome measures also varied significantly, including self-reported drug use, urine drug tests, and hair samples. High dropout rates in treatment studies raise concerns about attrition bias, and many studies were open-label, which could introduce bias. Crucially, a significant gap exists in patient-centered outcomes. Most studies focused on drug use markers rather than morbidity, mortality, or quality of life.

Recommendations

Shared, Informed Decision Making

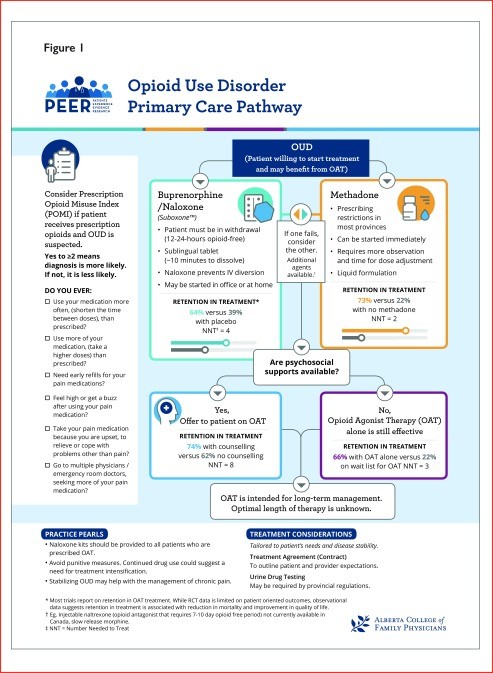

These guidelines are designed to facilitate shared, informed decision-making between clinicians and patients. A summary of recommendations is presented in Box 1, and Table 1 provides a comparison of treatment effects to aid in these discussions. Treatment algorithms and buprenorphine-naloxone induction pathways are also available (Figures 1 and 2) to further support clinical practice.

Box 1. Recommendations Summary.

Primary Care

- We recommend managing OUD in primary care as part of a comprehensive care approach. (Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence)

Diagnosis

- Clinicians could consider using a simple tool like the POMI to aid in identifying OUD in chronic pain patients. (Weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence)

Pharmacotherapy

- We recommend discussing buprenorphine-naloxone or methadone as treatment options for OUD. (Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence)

- Methadone may be more effective for treatment retention.

- Buprenorphine-naloxone may be easier to implement in primary care due to fewer restrictions.

- Clinicians could consider naltrexone for opioid-free patients unwilling or unable to use opioid agonist therapy (OAT). (Weak recommendation, low-quality evidence)

- We recommend against using cannabinoids for OUD management. (Strong recommendation, very low-quality evidence)

Prescribing Practices

- Clinicians could consider providing take-home doses (2–7 days) based on patient need and stability. (Weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence)

- Clinicians could consider urine drug testing as part of OUD management. (Weak recommendation, no RCT evidence)

- Clinicians could consider treatment agreements for some patients with OUD. (Weak recommendation, no RCT evidence)

- We recommend against punitive measures involving OAT (e.g., dose reduction or loss of carries) unless safety is a concern. (Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence)

Tapering

- We recommend against initiating OAT with short-term discontinuation in mind. OAT is intended for long-term management, potentially indefinitely. (Strong recommendation, low-quality evidence)

Psychosocial

- We recommend adding counseling to pharmacotherapy for patients with OUD when feasible. (Strong recommendation, low-quality evidence)

Residential Treatment

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against residential treatment for OUD. (No recommendation, no RCT evidence)

Comorbidities

- There is insufficient evidence to create specific recommendations for managing comorbidities like chronic pain, acute pain, insomnia, anxiety, and ADHD in patients with OUD. (No recommendation, insufficient evidence)

Note: Primary care settings in RCTs often included team-based care, support and training, substance misuse clinic affiliations, and 24-hour pager support. Availability of these supports will vary.

Table 1. Estimated Effects of Treatments in Opioid Use Disorder with GRADE Rating of Evidence

| TOPIC | INTERVENTION VS CONTROL | OUTCOME | ESTIMATED BENEFIT, % | FOLLOW-UP RANGE | NNT OR NNH | GRADE QUALITY OF EVIDENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTERVENTION | CONTROL | |||||

| Primary care | Specialty care | Treatment retention | 86 | 12–52 wk | 6 | Moderate |

| Primary care | Specialty care | Abstinence | 53 | 12–52 wk | 6 | Low |

| Pharmacotherapy | Placebo | Treatment retention | 64 | 30 d to 52 wk | 4 | Moderate |

| Methadone | No methadone | Treatment retention | 73 | 45 d to 2 y | 2 | Moderate |

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | Treatment retention | 60 | 2–52 wk | 7 | Moderate |

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | Abstinence | 30 | 2–52 wk | NSS | Low |

| Methadone | Buprenorphine | Sedation | 58 | 6 wk | 3 | Moderate |

| Naltrexone | Placebo or usual care | Treatment retention | 33 | 8–26 wk | 13 | Low |

| Naltrexone | Placebo or usual care | Abstinence | 39 | 8–26 wk | 9 | Low |

| Naltrexone | Placebo or usual care | Re-incarceration | 24 | 8–40 wk | 12 | Low |

| Supervised ingestion | Unsupervised ingestion | Treatment retention | 66 | 3–6 mo | NSS | Moderate |

| Supervised ingestion | Unsupervised ingestion | Illicit drug use | 59 | 3–6 mo | NSS | Low |

| Counseling | Minimal or no counseling | Treatment retention | 74 | 16–26 wk | 8 | Low |

| “Standard” counseling | Extended counseling | Treatment retention | 54 | 12–24 wk | NSS | Low |

| Positive contingencies | Usual care | Treatment retention | 75 | 6–26 wk | 11 | Moderate |

| Medication contingencies | Usual care | Treatment retention | 68 | 12–52 wk | 11 | Moderate |

Figure 1. Algorithm for Opioid Use Disorder Management in Primary Care

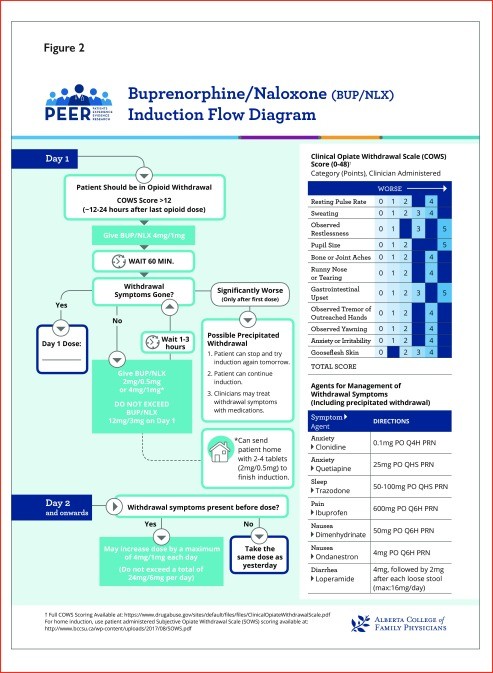

Figure 2. Buprenorphine-Naloxone Induction Pathway

These recommendations are intended to guide clinicians and patients in developing individualized treatment plans that consider patient preferences and values. It is crucial to integrate these guidelines with local regulatory requirements and standards. These recommendations are not intended for pregnant women or individuals under 18 years of age.

Management of OUD in Primary Care

Research indicates that managing OUD within primary care settings can lead to improved patient outcomes. Studies comparing primary care-based OAT programs to specialty care found that patients in primary care were more likely to adhere to treatment, avoid illicit opioids, and report higher satisfaction. These primary care models often included supportive team environments with nurses or pharmacists assisting with program administration, provider education, and access to 24-hour support. However, even when these comprehensive supports are not fully available, OAT alone has demonstrated significant benefits in primary care settings, including improved treatment retention, well-being, and reduced illicit opioid use compared to placebo or waiting-list controls. Therefore, similar to other chronic conditions, OUD management should be integrated into primary care as a routine part of patient care.

Diagnosis of OUD

The DSM criteria remain the gold standard for OUD diagnosis. However, their complexity and time requirements may limit their practicality in busy primary care settings. While various screening tools exist, the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI) shows promise for identifying OUD in chronic pain patients taking opioids. This brief, 6-item checklist can assist clinicians in identifying potential OUD, with a score of 2 or more suggesting a higher likelihood of OUD in patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) is another option, but its length may be less suitable for primary care. Other tools lack validation against DSM criteria in OUD populations. Thus, clinicians could consider using the POMI as a simple aid in identifying OUD, particularly in chronic pain patients.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy is a cornerstone of OUD treatment. While studies haven’t been powered to definitively assess mortality or overdose reduction, combined data suggest that pharmacotherapy for OUD is associated with reduced all-cause mortality. Buprenorphine and methadone are both effective in improving treatment retention compared to placebo. Methadone has demonstrated superior retention rates in direct comparisons with buprenorphine, although opioid abstinence rates appear similar between the two. Buprenorphine-naloxone may be easier to implement in primary care due to fewer regulatory hurdles. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is another option for patients who have achieved opioid abstinence and are not willing to use OAT. However, it requires a 7-10 day opioid-free period to avoid precipitated withdrawal and may be more suitable for patients with prior detoxification, such as those transitioning from incarceration. Sustained-release oral morphine (SROM) is an alternative, but evidence is limited, and high doses are often needed. Cannabinoids are not recommended for OUD management due to a lack of evidence supporting their benefit. Overall, pharmacotherapy is strongly recommended for OUD. Methadone may offer better retention, but buprenorphine-naloxone presents a more practical option for many primary care settings.

Prescribing Practices

Strategies like daily witnessed ingestion, urine drug testing, and treatment agreements are sometimes used to mitigate risks associated with OAT. However, these practices can be burdensome for patients and create barriers to care.

Daily Witnessed Ingestion: Evidence suggests that “unsupervised” take-home doses of OAT are generally comparable to “supervised” ingestion in terms of patient outcomes. Most studies compared varying levels of supervision rather than strict daily witnessed ingestion versus unsupervised carries. No significant differences were found in mortality or overdose rates. Some data suggest unsupervised carries may even reduce medication diversion. Treatment retention rates are similar regardless of supervision level. Therefore, providing take-home doses when appropriate based on patient stability and need is a reasonable approach.

Urine Drug Testing: Limited evidence supports routine urine drug testing in OUD management. One retrospective study suggests potential benefits, but confounding factors cannot be ruled out. Urine drug testing should not be punitive but can be used to identify potential instability and inform treatment intensification.

Treatment Agreements (“Contracts”): Treatment agreements can enhance communication and clarify expectations. However, evidence specifically evaluating their impact in OUD is limited. Studies incorporating treatment agreements often also included contingency management strategies, making it difficult to isolate the effect of agreements alone. Despite limited direct evidence, treatment agreements can be considered to improve communication and set clear boundaries.

Tapering Therapy

Tapering strategies in OUD management require careful consideration.

Tapering from Prescribed Opioids: No RCTs have specifically examined tapering prescribed opioids as a therapeutic intervention for OUD.

Tapering OAT vs. Indefinite OAT: Evidence indicates that continuing OAT leads to better treatment retention and reduced drug use compared to tapering off OAT. Patients attempting to taper OAT often experience relapse or study withdrawal. OAT is intended for long-term management, and abrupt discontinuation is generally not recommended.

Fast vs. Slow OAT Tapering: When tapering OAT is considered, slower tapering protocols (28-56 days) are associated with fewer withdrawal symptoms and higher patient satisfaction compared to rapid tapers (7-28 days). If OAT discontinuation is contemplated, it should be a slow, individualized process.

Psychosocial Interventions

Adding psychosocial interventions to pharmacotherapy improves treatment outcomes. Standard counseling (brief, regular sessions) significantly enhances treatment retention compared to minimal counseling. Extended counseling sessions do not appear to provide additional benefit over standard counseling. Brief motivational interviewing also shows promise in improving retention. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has not demonstrated improved retention compared to standard care that includes regular physician contact. Therefore, integrating brief psychosocial interventions like counseling with pharmacotherapy is recommended when available. Computer-delivered psychosocial interventions may offer a viable alternative when access to in-person counseling is limited.

Contingency management, encompassing both rewards and punishments, has yielded mixed results when analyzed as a whole. However, positive contingency management (using rewards) improves treatment retention, while negative contingencies (punishments like dose reduction or loss of take-home doses) are detrimental, decreasing retention and not reducing illicit drug use. Positive reinforcement strategies should be prioritized, and punitive measures should be avoided unless patient or community safety is at immediate risk.

Residential Treatment

The effectiveness of residential treatment programs for OUD remains unclear due to a lack of RCTs. Variability in program components and restrictions on OAT use within some programs further complicate evaluation. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations for or against residential treatment.

Management of Comorbid Conditions in Patients with OUD

Managing co-occurring conditions in patients with OUD is complex and under-researched. Evidence-based guidance is lacking for many common comorbidities. For acute pain management in patients on OAT, morphine may be preferable to meperidine in emergency settings, but non-opioid options require further exploration, particularly in ambulatory care. Chronic pain management in patients with OUD is also challenging. Tapering OAT in chronic pain patients is often unsuccessful. Limited evidence suggests buprenorphine and methadone may be comparable for pain control. For other comorbidities like insomnia, anxiety, and ADHD, evidence is sparse, with limited RCTs showing no benefit beyond placebo. While specific recommendations are lacking, all patients with OUD deserve standard care for comorbid conditions, integrated with their OUD treatment.

Practice Pearls

Based on expert opinion and current practice trends, the Guideline Committee offers the following practice pearls:

OAT

- Emphasize harm reduction, including naloxone kit provision.

- Require lockboxes for take-home OAT doses.

- Buprenorphine-naloxone doses can exceed 24 mg/day in select cases, up to 32 mg/day.

- To address sedation concerns with dose increases, have patients take their dose in the morning and assess sedation levels a few hours later.

- Titrate OAT dose based on withdrawal symptoms, focusing on symptoms worst just before the next dose.

- Be aware of OAT side effects similar to opioids (constipation, amenorrhea, low testosterone), and methadone-specific sweating.

- Stabilize OUD before addressing chronic pain; pain may improve with OUD stabilization.

- OAT can be used in polysubstance use disorder.

- For safety-sensitive jobs, consider employer drug testing policies and pharmacotherapy management.

- Investigate potential diversion if urine drug tests are negative for prescribed OAT medications.

Withdrawal Symptoms

- Untreated withdrawal can last weeks; treatment (e.g., buprenorphine) typically resolves symptoms within 3-5 days with proper titration.

- Familiarize yourself with opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms; correlate physical exam findings with patient reports.

- Recognize craving as a withdrawal symptom.

Access Additional Resources

- Consult community pharmacists for insights into patient status (sedation, intoxication).

- Utilize mentorship networks for managing comorbidities or complex OUD cases.

Box 2. Practice Pearls: Opinions of the Guideline Committee and Current Practice Trends.

OAT

- Promote harm reduction, such as ensuring patients have a naloxone kit

- Patients must have a lock box for take-home doses or “carries” of OAT

- Despite most references stating that the maximum dose of buprenorphine-naloxone is 24 mg/d, the dose can be increased up to 32 mg/d in select cases

- If unsure about raising the OAT dose owing to sedation concerns, ask patients to take their dose in the morning and rebook an appointment 3–4 h after the dose to ensure they are not overly sedated

- Titrate the dose of OAT based on withdrawal symptoms. Ask about the time of day that withdrawal symptoms are the worst. True withdrawal symptoms are worst right before the next dose is due

- Side effects of OAT are similar to those seen with opioids including constipation, amenorrhea in female patients, and low testosterone in male patients

- Methadone can cause sweating, which can also be a withdrawal symptom

- For patients with chronic pain, first stabilize the OUD before managing pain

- Pain outcomes might improve as OUD stabilizes

- OAT can still be used in the context of polysubstance use disorder (eg, OUD and stimulant use disorder)

- If patients are employed in safety-sensitive jobs, check employer standards for urine drug testing and pharmacotherapeutic management

- If a urine drug test result is negative for methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone (or their metabolites) in a patient taking OAT, consider the possibility of diversion

Withdrawal symptoms

- Untreated, withdrawal symptoms might last for weeks. With treatment (eg, buprenorphine), they will usually settle within 3–5 d depending on titration

- Familiarize yourself with opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms. Do the physical examination findings correlate with the patient’s subjective report of symptoms?

- Craving is a withdrawal symptom

Access additional resources

- Access community pharmacists to gather information on patients you are concerned about. How do they look when they come in? Are they sedated or intoxicated?

- Consider mentorship networks, if available, to help manage comorbidities (eg, pain) or to discuss alternative management for patients with suboptimal response to OAT, etc

Conclusion

Managing OUD in primary care with long-term OAT, combined with psychosocial support and avoidance of punitive measures, can significantly improve patient outcomes. Treatment decisions should always be made in collaboration with patients, considering their preferences and values. Future research should focus on clarifying the long-term effects of pharmacotherapy on mortality, morbidity, and social functioning, as well as optimizing the management of comorbidities and refining diagnostic approaches for OUD in chronic opioid users.

References

[1] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[2] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[3] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[4] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[5] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[6] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[7] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[8] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[9] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[10] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[11] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[12] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[13] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[14] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[15] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[16] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[17] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[18] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[19] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[20] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[21] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[22] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[23] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

[24] ‡Citation missing from original article‡

*Full disclosure of competing interests, summarized GRADE results, the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index, a list of upcoming dosage forms for buprenorphine and naltrexone, and additional resources are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.