Introduction

The ‘2023 AAFP/IAAHPC Feline Hospice and Palliative Care Guidelines’ represent a significant advancement in veterinary medicine, offering a comprehensive framework for approaching end-of-life care for cats. Developed by a task force of experts convened by the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and the International Association for Animal Hospice and Palliative Care (IAAHPC), these guidelines emphasize crucial communication skills, ethical considerations, and practical strategies for providing optimal palliative care diagnosis and management. While referencing other feline practice guidelines for detailed discussions on specific diseases and pain management, this document focuses on the holistic approach necessary for feline hospice and palliative care. A cornerstone of these guidelines is the multi-step hospice consultation, which allows for a personalized care plan tailored to each cat and their family. This includes establishing ‘budgets of care’, acknowledging the diverse resources available to each caregiver, and introducing the concept of the ‘care unit’, empowering caregivers to actively participate in their cat’s care journey. Ethical decision-making is supported by a clear framework, and the importance of comfort care and quality of life assessment is thoroughly reviewed. Recognizing the interconnectedness of physical and emotional health, the guidelines underscore the impact of compromised physical health on a cat’s emotional well-being. Euthanasia is discussed as a compassionate option, with reference to the AAFP’s End of Life Educational Toolkit for further guidance on ensuring a peaceful passing that honors both the cat’s and caregiver’s needs.

Hospice and palliative care for cats addresses the multifaceted needs – physical, psychological (emotional), and social – of patients facing chronic or life-limiting illnesses. 1 Veterinary professionals must be proficient in communication, consultation for hospice/palliative care, and comfort care options to effectively support feline patients and their families during this sensitive time. Recognizing that physical health issues, including pain and illness, significantly impact emotional well-being is paramount. Bond-centered care, which integrates the non-medical needs of caregivers with the medical needs of their cats, is fundamental. This approach strengthens the human-animal bond and is central to achieving the goals of feline hospice and palliative care.

Defining Hospice and Palliative Care in Veterinary Practice

Hospice and palliative care have emerged as vital disciplines within veterinary medicine since the early 2000s. Inspired by advancements in human hospice care and the deepening human-animal bond, cat families increasingly seek compassionate end-of-life care philosophies for their feline companions.

- ✜ Hospice care is initiated when a cat receives a diagnosis of a life-limiting illness, and the focus of medical care shifts from curative treatments to maximizing comfort and quality of life (QOL). Feline hospice care holistically addresses the physical, emotional, and social needs of cats in advanced stages of disease, while also supporting the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of their caregivers. A multidisciplinary healthcare team, overseen by a licensed veterinarian, best serves the needs of both cats and their caregivers. 1

- ✜ Palliative care is applicable at any stage of illness, whether curable or incurable. It prioritizes alleviating clinical signs and providing comfort care to enhance the patient’s well-being.

Figure illustrating the difference between Hospice and Palliative Care, emphasizing the shift from curative to comfort focused care in hospice.

Expanding the ‘Unit of Care’

A fundamental principle in feline hospice and palliative care is the expanded ‘unit of care’. The veterinary team’s focus extends beyond the feline patient to include the caregivers and their needs. This approach advocates for collaboration between veterinary professionals and social workers, support charities, and mental health experts. This interdisciplinary collaboration facilitates transparent communication regarding treatment preferences and goals of care, a cornerstone of modern end-of-life care. Addressing the psychological, social, and spiritual needs of caregivers requires a team approach, as veterinary professionals alone are not comprehensively trained in these areas. The interdisciplinary hospice and palliative care team can encompass groomers, cat sitters, clergy, extended family, general practice veterinarians, specialists, veterinary technicians, and dedicated hospice and palliative care providers – all contributing to a holistic support system.

Honoring the human-animal bond is a guiding principle in hospice and palliative care. A primary goal is to ensure this bond remains strong and supportive throughout the intensive caregiving often required at the end of a cat’s life. Many veterinarians in this field are motivated by the opportunity to support families through the end-of-life journey and subsequent grief, facilitating healthy grieving and potentially future pet adoptions. The strength of the human-animal bond drives the increasing demand for hospice and palliative care services. Bond-centered care empowers families, ensuring they are central to decision-making and caretaking, meeting both their cat’s and their own needs. The ‘five-step hospice and palliative care plan’ (detailed later) is designed with this bond-centered approach at its core.

Ethical Framework for Feline Palliative Care Diagnosis

Hospice and palliative care inherently value the alleviation and prevention of suffering. However, the end-of-life phase raises complex spiritual and moral considerations. Veterinary professionals navigate diverse perspectives on the appropriateness of ending a life. The language used in feline hospice and palliative care is continually evolving to better address end-of-life situations. Terms like ‘hospice-assisted death’ or ‘palliated death’ are gaining traction to clarify the veterinary role in enhancing a cat’s quality of death when euthanasia is not chosen. The previously used term ‘natural death’ can be misleading and influence family decisions. Refining veterinary terminology is crucial for minimizing miscommunication and ethical dilemmas in end-of-life care.

Diagram illustrating the ethical considerations in feline palliative care, highlighting the balance between extending life and ensuring quality of life.

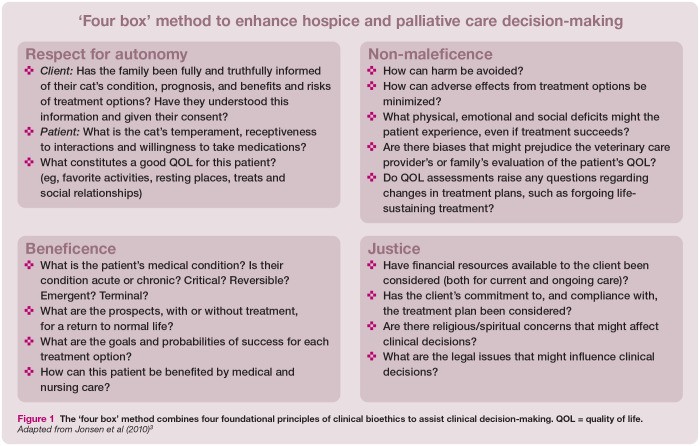

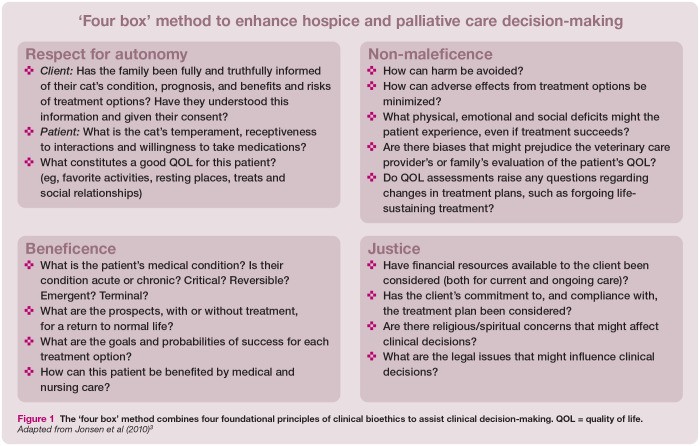

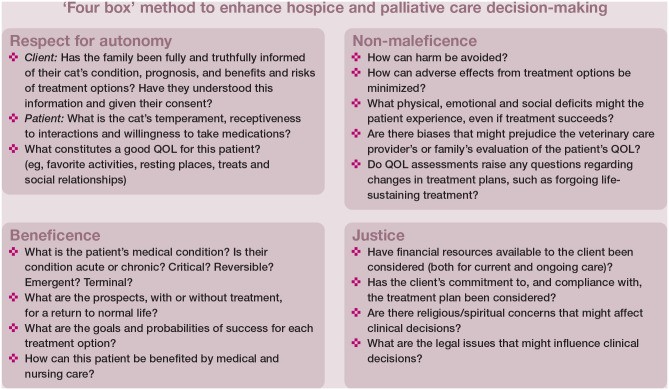

Feline hospice and palliative care case management and communication with the caregiver and care unit should be guided by four fundamental principles of clinical bioethics. Bioethics examines the ethical, social, and legal issues in medicine and biomedical research. Clinical bioethics applies ethical principles to medical practice. These four principles are:

- ✜ Respect for autonomy – supporting informed decision-making about care without coercion.

- ✜ Non-maleficence – avoiding harm to patients.

- ✜ Beneficence – acting in the patient’s best interests.

- ✜ Justice – ensuring fairness and equity in treatment recommendations. 2

Figure 1 demonstrates the ‘four box’ method, integrating these bioethical principles to aid clinical decision-making. These principles are not a unified ethical theory but offer a framework for evaluating individual cases. Applying this framework to hospice and palliative care involves balancing these principles to determine the best course of action for the patient. When applying bioethical principles to end-of-life care for cats, veterinary professionals acknowledge the limitation of not having self-reporting patients, while striving to optimize outcomes (minimizing suffering and ensuring a peaceful death). The individual cat’s needs and moral consideration are central to this process (see box ‘Cats deserve moral consideration’).

Figure 1.

The ‘Four Box’ Method for Ethical Decision-Making in Feline Palliative Care. Adapted from Jonsen et al (2010) 3

Delving into Bioethical Principles

Respect for Autonomy

Respect for client autonomy means that veterinary professionals must clearly communicate information necessary for caregivers to make informed decisions on behalf of their cats. This involves explaining expected outcomes, risks, and benefits of treatment options in understandable language, enabling caregivers to make informed choices. Supporting caregiver autonomy includes: honesty about the cat’s condition and prognosis, respecting caregiver values and confidentiality, obtaining consent before treatment, and assisting with decision-making when requested.

Respect for the patient’s autonomy considers the cat’s temperament, receptiveness to interactions, and willingness to accept medications – their engagement in their own care. Forcing medications or painful procedures on a cat exhibiting fear and anxiety, potentially leading to defensive behaviors, violates their autonomy. Such actions can also damage the bond between the cat, caregiver, and care unit. Finally, respecting the cat’s will to live, though abstract, is part of respecting autonomy. QOL scales offer a strategy for caregivers and the care unit to objectively assess this subjective aspect of the cat’s situation (discussed in ‘Other tools’).

Non-maleficence and Beneficence

Non-maleficence and beneficence are interwoven in feline hospice and palliative care. For caregivers and the care unit, these principles mean avoiding harm through incomplete or insensitive communication and providing the benefit of open and honest discussions about prognosis and costs. For feline patients, these principles guide decisions about procedures and interventions. Benefits must outweigh potential harms or burdens. Each step of the palliative care plan must be evaluated for its impact on the cat’s well-being.

Non-maleficence and beneficence align with the cat’s willingness to participate in care. While cats may not fear death, they do anticipate and fear pain.7,9–12 Pain associated with interactions, medications, or treatments must be anticipated, identified, and prevented. In cases of unmanageable pain, non-maleficence and beneficence necessitate discussing humane euthanasia to relieve suffering.

Justice

The bioethical principle of justice emphasizes fairness to the caregiver, the care unit, and the cat in hospice and palliative care. Veterinary teams should provide their best efforts regardless of the caregiver’s background or the cat’s history. Fairness includes considering the caregiver’s financial resources, commitment to the care plan, adaptability to hospice care’s flexibility, and adherence to recommendations. Justice also means treating each cat based on their individual preferences and acceptance of treatment.

Bioethical Framework in Practice

All four bioethical principles should inform a systematic approach to feline hospice and palliative care. Beyond direct care decisions, bioethics guides communication with caregivers about the expected illness trajectory, mitigating the risk of unforeseen outcomes. Illness trajectories are typical patterns of disease progression. 13 Four common trajectories are: 14

- ✜ Type 1 trajectory: Rapid decline near death (days to weeks), often seen in cancer.

- ✜ Type 2 trajectory: Chronic illness followed by sudden death after compensatory mechanisms fail; fluctuating clinical signs and increasing care burden, e.g., cardiac disease progressing to heart failure.

- ✜ Type 3 trajectory: Slow, steady decline with prolonged care and potential secondary complications like urinary tract infections, e.g., feline chronic kidney disease.

- ✜ Type 4 trajectory: Sudden, severe neurological or circulatory event resulting in extreme impairment, requiring invasive and often futile care, e.g., feline saddle thrombus.

Understanding illness trajectories is crucial for veterinary teams to grasp the full impact of disease on each patient.

Communication Strategies for Compassionate Palliative Care Diagnosis

The transition to hospice and palliative care is a profound experience for cat caregivers, with lasting emotional impact. Veterinary professionals must recognize the psychological and emotional consequences of this care and communicate in ways that minimize caregiver distress.

Effective communication builds trust between the veterinary team and caregivers. It forms the basis for establishing goals and treatment plans for hospice and palliative care. Veterinarians and their teams need to understand a caregiver’s needs, beliefs, goals, and budgets (financial, time, physical, and emotional), shaped by their life experiences. This understanding enhances communication, strengthens the veterinary-client-patient relationship, builds trust and respect for recommendations, guides diagnostic and treatment choices, improves care efficiency, eases caregiver anxiety, reduces emotional strain on the care unit, and minimizes potential conflict.

Observational skills and targeted questions are vital during initial consultations. Caregivers need to feel heard and safe to share personal beliefs, family dynamics, and financial situations. Compassionate and non-judgmental communication is essential.

Diverse Roles of the Veterinarian in Communication

Veterinarians (and team members) may assume different communication roles: expert, expert guide, partner, or facilitator. The expert role involves diagnosis and educating caregivers about disease trajectories. The expert guide role is seen in euthanasia decision-making and support through the procedure. As a partner, the veterinarian supports the caregiver’s choices, regardless of their care decisions. As a facilitator, the veterinarian helps realize the caregiver’s wishes. Aligned communication occurs when roles are appropriately matched to the situation.

Image depicting a veterinarian communicating empathetically with a cat caregiver, illustrating the expert guide or partner role.

Guiding Caregivers Through Palliative Care Consultation

Veterinarians should initiate consultations with open-ended questions (What, Where, When, Who, Why, How) or indirect statements (“Please describe…”). Observe caregiver body language:

- ✜ Moving away: discomfort or stress.

- ✜ Protective of cat: need for time, emotional support.

- ✜ Avoiding eye contact: discomfort, cultural, emotional reasons.

When delivering upsetting information, use ‘signposts’ or ‘road maps’ to prepare caregivers, such as:

- ✜ “I am worried about what I am seeing here.”

- ✜ “We are finding ourselves about to experience a big change.”

- ✜ “We are going to have some hard decisions to make.”

- ✜ “We are facing a challenge.”

- ✜ “Your cat is going to need us more than ever before.”

- ✜ “We are approaching a new chapter in his/ her life.”

These statements guide the conversation. Ask permission to continue (“Are you ready for me to continue?”) to create a safe space. Use the ‘chunk and check’ technique 16 – breaking down information into manageable chunks and checking for understanding (“Do you follow what I’ve just shared?”) – to prevent information overload. Establish common ground with back-and-forth communication, recognizing, endorsing, and acknowledging statements to encourage feedback and collaboration.

Relationship-Centered Care and Goals of Care

Relationship-centered care and goals of care are valuable concepts in palliative care consultations. 17,18 Relationship-centered care emphasizes shared decision-making after the veterinarian has fulfilled their bioethical duty to educate the caregiver in understandable terms. Kuper and Merle (2019) 17 highlighted the importance of balanced power between veterinarian and caregiver in decision-making, avoiding paternalistic approaches or a purely customer-provider dynamic, which can lead to dissatisfaction and inefficient care.

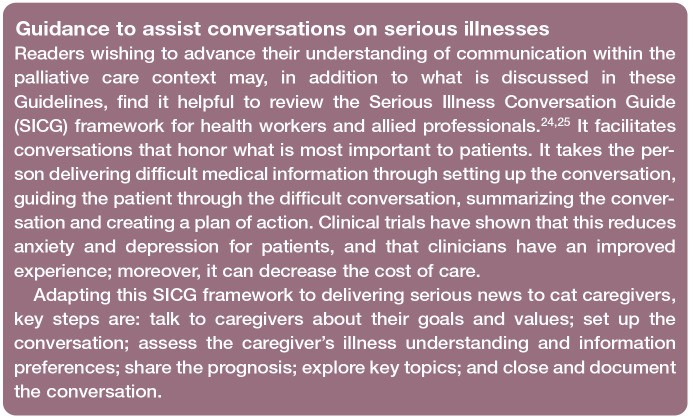

Goals-of-care conversations are essential for palliative care in both human and animal patients. 18 High-quality goals-of-care conversations are vital for advancing palliative care. They provide crucial support for caregivers navigating their cat’s illness and making end-of-life decisions. Frameworks exist to guide communication techniques to clarify caregiver understanding of their cat’s health status 19–21 and their information needs. These models help manage stress associated with delivering bad news and improve caregiver satisfaction.

Key elements for successful communication include choosing a private, comfortable setting without interruptions, ensuring all stakeholders are present, and allowing ample time. Determine what the caregiver knows and how much detail they want. Share information accordingly, using simple language and explaining medical jargon. Warn of difficult news (“This might be hard to hear”). Empathy is crucial – assure caregivers of your care and support. Offer empathetic statements like, “As a veterinarian, my priority is your cat’s well-being, and I’m here to support you both.” Be direct and transparent when delivering difficult news.

Manage caregiver reactions by listening to concerns and validating emotions. Allow space for emotional expression. Conclude by summarizing, addressing questions, and outlining the care plan and next steps.

Caregiver Communication Preferences

Veterinary professionals should understand caregiver communication preferences. A study by Englar et al (2016) 23 found:

- ✜ Cat caregivers value chunk and check and signposting more than dog caregivers.

- ✜ Cat caregivers emphasize empathy more than dog caregivers.

- ✜ Cat caregivers appreciate focus on their cat.

- ✜ Cat caregivers use ‘we’ to include their cat, while dog caregivers use ‘I’.

- ✜ Cat caregivers are seen as caretakers, dog caregivers as masters.

- ✜ Cat caregivers are passengers, dog caregivers are drivers in the veterinary visit.

- ✜ Cat caregivers accept veterinarian leadership with signposting.

- ✜ Cat caregivers prioritize communication to lessen distress and fear.

- ✜ Cat caregivers value all veterinary team members.

Image illustrating empathetic communication between a veterinarian and a cat caregiver, highlighting the importance of emotional connection in feline care.

Five-Step Hospice and Palliative Care Plan

The following five-step plan provides a framework for veterinary teams to consistently implement effective hospice and palliative care for feline patients.

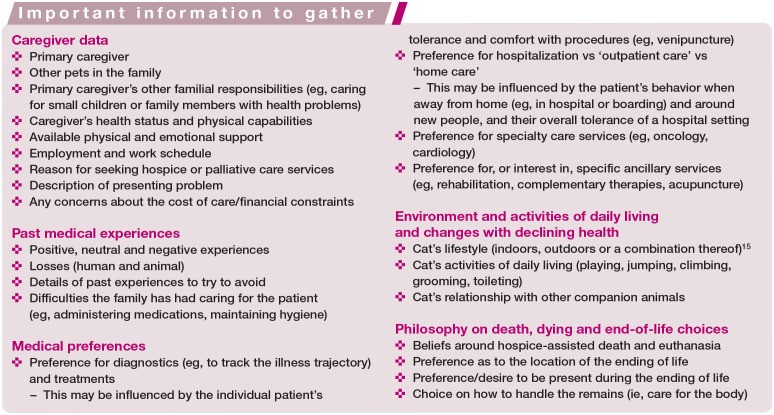

Step 1: Evaluating Caregiver Needs, Beliefs, and Goals

Caregiving needs vary greatly, influenced by disease severity and progression. Veterinary professionals must explore caregiver needs, beliefs, and goals, as their active involvement is crucial. This information guides treatment planning.

Frame conversations around ‘personal budgets’ – financial, emotional, physical, and time resources available to the caregiver. 26 Examples include:

- ✜ Financial: Can I afford care? Will it strain finances?

- ✜ Emotional: Can I emotionally manage this? Will it negatively affect me? Do I have the emotional capacity given other responsibilities?

- ✜ Physical: Will care interfere with my physical well-being (e.g., sleep loss with feline cognitive dysfunction)? Can my cat physically receive care (medications, fluids)?

- ✜ Time: Do I have the time required? Do work and daily life align with care needs? Will I have support from family or friends?

Understanding caregiver needs, beliefs, and goals requires open-ended questions and caregiver experience/goal sharing. Discuss personal budgets, balancing quality and duration of life, treatment goals, and euthanasia or hospice-assisted death preferences. Encourage questions and avoid rushing or pressuring decisions. Caregivers should never feel judged, regardless of their choices.

Step 2: Educating on Disease Process and Care Delivery

The primary goal of caregiver education in hospice and palliative care is to ensure clear understanding of diagnostic and treatment options for cat comfort, expected disease trajectory, and prognosis. Informed caregivers can better participate in the care unit with realistic expectations and make informed decisions. Veterinary teams should communicate clearly and simply, ensuring caregivers fully understand all options before making care decisions.

Caregiver education on care delivery should include verbal, written, and visual instructions (illustrations, videos). Use a ‘see one, do one, teach one’ approach for tasks like subcutaneous fluid administration.

Image demonstrating a veterinarian teaching a caregiver how to administer subcutaneous fluids to their cat, emphasizing hands-on education.

Step 3: Developing a Personalized Plan

Developing a patient-specific hospice and palliative care plan (Figure 2) is a collaborative effort involving the veterinary team, caregiver, and care unit. Key components include:

Figure 2.

(a) Feline patient before personalized hospice care. (b) Same patient after care plan implementation, including pain control, nutrition, and comfort care. Images courtesy of Clara Showalter and Katrina Breitreiter

- ✜ Assessing caregiver capability and willingness to take on specific care responsibilities.

- ✜ Assessing patient willingness and capacity to receive care.

- ✜ Creating a detailed, written, and understandable plan.

- ✜ Estimating time commitment for care.

- ✜ Estimating costs (rechecks, diagnostics, medications, supplies).

- ✜ Establishing a follow-up communication and reassessment schedule.

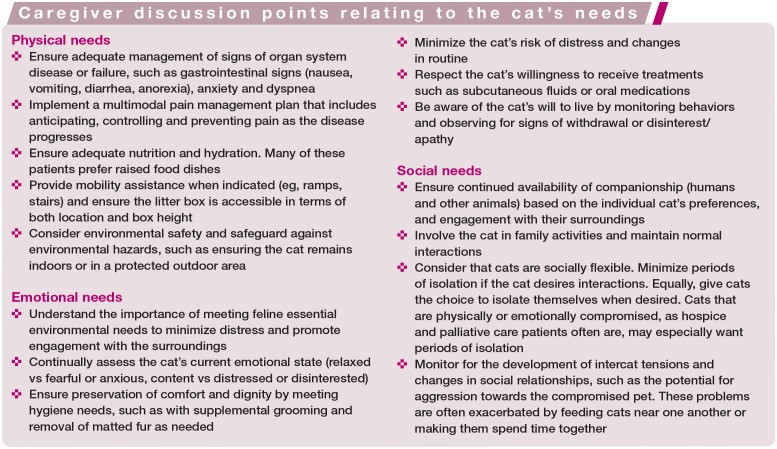

Approach care plan creation by considering physical, emotional, and social needs. The box ‘Caregiver discussion points relating to the cat’s needs’ summarizes assessment areas.

Step 4: Applying Hospice or Palliative Care Techniques

A hospice and palliative care plan empowers caregivers to provide home care. Care plan execution involves instructing caregivers on therapeutic techniques, assessing cat response to treatments, and recognizing signs of decline.

Guide caregivers on safe cat interaction and handling, including safe medication and fluid administration. Medication administration should be positive (e.g., medication in treats) or followed by positive interaction. Evaluate the home environment for comfort and safety, making necessary adaptations, such as improving food/water access, comfortable bedding, optimized litter box location, ideal temperature, or safe heat sources.

Technologies like asynchronous video communication or synchronous telehealth can facilitate regular communication between caregivers and the veterinary team regarding the patient’s status.

If caregivers decline diagnostics or treatment, avoid guilt-tripping and support their difficult decisions. Declining bloodwork for chronic kidney disease does not mean stopping supportive care like fluids or medications. Always ensure families feel supported and comforted in their decisions.

Step 5: Emotional Support During and After Care

Emotional support and empathy are essential from the beginning of end-of-life care and are the responsibility of the entire veterinary practice. Continuously assess caregivers for anticipatory grief, which mirrors post-mortem grief (denial, anger, depression, acceptance) and can complicate decision-making. Anticipatory grief may manifest as rehearsing the loss or obsessive monitoring. 27 Disenfranchised grief 28 is also common, where caregivers grieve without adequate support because others don’t validate their loss.

Encourage grieving caregivers to seek support and provide resources like support groups. Simply naming and normalizing anticipatory, post-mortem, or disenfranchised grief is helpful. For caregivers struggling with grief, consider a multidisciplinary approach involving social workers and mental health professionals. Most importantly, validate and support caregivers’ feelings.

Image depicting a veterinary professional offering emotional support to a grieving cat caregiver, emphasizing the importance of compassion and empathy in end-of-life care.

Quality of Life Assessment in Feline Palliative Care Diagnosis

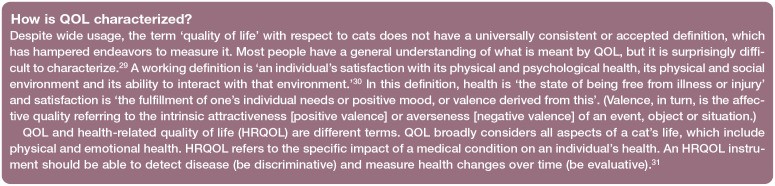

“How will I know it’s time?” is a common caregiver question. Partnering with them in euthanasia decisions is a critical veterinary role. Disease and treatment effects impact QOL. With advanced treatments available, prioritize patient interests over caregiver pressure. 26 Just because we can prolong life doesn’t mean we should; quality, not quantity, is paramount.

Cats live in the present and don’t understand future improvement during unpleasant treatments. Caregivers and veterinary teams must make patient-centered decisions together. Discussing the meaning of QOL is essential (see box ‘How is QOL characterized?’).

QOL assessment is vital in palliative and hospice care to determine if a cat has a life worth living. As cats can’t self-report, QOL is assessed through direct observations by caregivers and veterinarians (observer-related outcomes). QOL is subjective and individual. Pain, an unpleasant emotion, is not the only negative feeling in chronic disease. Consider nausea, thirst, breathlessness, and fear-anxiety (Table 1). QOL assessment is further discussed in the ‘2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines’ (catvets.com/senior-care). 26

Table 1.

Examples of physical, emotional, and social factors that contribute to poor QOL

| Physical factors |

|---|

| ✜ Chronic (maladaptive) pain – eg, DJD, dental disease, non-healing wounds |

| ✜ Nausea and vomiting – eg, secondary to chronic kidney disease |

| ✜ Breathlessness – eg, respiratory disease, congestive heart failure |

| ✜ Thirst – eg, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease |

| Emotional and social factors |

| ✜ Fear-anxiety |

| ✜ Isolation and loneliness |

| ✜ Boredom |

| ✜ Frustration |

| ✜ Distress |

Table listing factors that can negatively impact a cat’s quality of life, categorized into physical and emotional/social aspects.

Validated QOL Instruments

Experts prioritize feline welfare issues. 32 Diseases of old age are ranked second in welfare priority, and delayed euthanasia is second for prevalence. QOL and HRQOL instruments monitor treatment effectiveness and aid euthanasia decisions. Veterinarians should ask caregivers what matters to them regarding their cat’s QOL.

QOL instruments exist for specific diseases: cardiac disease, 33 diabetes mellitus 34, and skin disease 35. However, aging cats often have multiple conditions, necessitating generic HRQOL instruments. 36 A 20-item online caregiver instrument reliably distinguishes sick from healthy cats and tracks chronic feline diseases. 31 Developed using cats with DJD, cardiac, dental, renal, urinary, gastrointestinal diseases, and cancer, it assesses vitality, comfort, and emotional well-being. This tool is available for clinical use through NewMetrica (newmetrica.com) for a fee.

Other QOL Assessment Tools

Many unvalidated tools can still be valuable for engaging caregivers in tracking their cat’s QOL. These include:

Comfort Care Strategies for Feline Palliative Care Diagnosis

Comfort care is paramount for hospice and palliative care, addressing physical, emotional, and social needs. This section focuses on physical needs, particularly pain recognition and control. Emotional and social needs are discussed later in ‘Feline emotional health’.

Impact of Pain on Feline Well-being

Pain significantly diminishes QOL in feline patients. Both acute and chronic pain are relevant in hospice and palliative care. Acute pain occurs during normal healing after tissue injury (trauma, surgery, diagnostics, acute conditions). Chronic pain persists beyond normal healing or arises from non-healing conditions. 37 Chronic pain is maladaptive, serving no biological purpose and persisting. 38

Most feline hospice and palliative care patients experience at least one painful condition, such as DJD, cancer, post-surgical pain, gastrointestinal issues, neuropathic disorders, trauma, chronic wounds, skin or ocular conditions, feline lower urinary tract disease, or diabetic neuropathy. 38 Pain severity doesn’t always correlate with lesion severity, and the pain source may be unidentified.

Pain can alter feline behavior: withdrawal, hiding, abnormal sleeping positions, hunched posture, decreased appetite, reduced movement, reluctance to jump or climb, diminished activity, difficulty rising/walking, decreased grooming, and changes in elimination habits, squinting, touch sensitivity, and aggression. 37 These changes negatively impact the human-animal bond. 38

Recognizing Pain in Cats

Identifying and addressing pain in hospice and palliative care aligns with bioethical principles and is a moral imperative. Pain is a vital sign, alongside temperature, pulse, respiration, and nutrition. 37,39

Cats are adept at hiding pain, and caregivers may not recognize their discomfort. Providing caregivers with pain recognition tools is crucial. Validated tools for acute and chronic pain are highlighted below; comprehensive lists are in Tables 4 and 7 of the ‘2022 WSAVA Guidelines for Pain Recognition’. 40 The ‘2022 AAHA Pain Management Guidelines’ 37 and ‘2022 ISFM Acute Pain Guidelines’ 41 offer practical recommendations. The AAFP’s brochure ‘How do I know if my cat is in pain?’ (catfriendly.com/pain) helps caregivers recognize feline pain.

Table 4.

Dosing recommendations for monoclonal antibody therapy in cats

| Monoclonal antibody drug | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Frunevetmab (anti-nerve growth factor antibody) | ✜ Cats 5.5-15.4 lb (2.5-7.0 kg): 7 mg (a single vial) SC q30 days ✜ Cats 15.5-30.8 lb (>7.0-14 kg): 14 mg (two vials) SC q30 days | ✜ Should not be administered to breeding cats or to pregnant or lactating queens ✜ Extreme caution should be taken to avoid self-injection in women who are pregnant, trying to conceive or breastfeeding |

Table outlining dosage and considerations for Frunevetmab, a monoclonal antibody for pain management in cats.

Table 7.

Dosing recommendations for appetite stimulants in cats

| Appetite stimulant | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Mirtazapine | 2 mg (¼ inch [~0.5 cm] strip) applied to the inner pinna q24h | ✜ Safety and efficacy of the transdermal formulation appears superior to oral administration, particularly when the human tablet formulation is split ✜ Dose-dependent side effects include hyperactivity and restlessness ✜ The transdermal formulation may cause local irritation at the site of application |

| Capromorelin | 2 mg/kg PO q24h | ✜ The feline formulation differs significantly from the canine formulation, which should be avoided in cats ✜ Contraindicated in patients with diabetes or acromegaly |

Table detailing dosage and considerations for Mirtazapine and Capromorelin, appetite stimulants used in feline palliative care.

Acute Pain Assessment

At least three validated pain-scoring systems exist for cats. The UNESP-Botucatu multidimensional feline pain assessment scale short form (UFEPS-SF) uses posture, comfort, activity, attitude, and reaction to touch to assess pain. 42 The Glasgow composite measure pain scale-feline (Glasgow CMPS-Feline) is a longer checklist starting with undisturbed cat observation and including facial features. 43,44 The Feline Grimace Scale evaluates five facial ‘action units’ (ear position, orbital tightening, muzzle tension, whisker position, head position) for pain. 45 A downloadable phone app is available for the Feline Grimace Scale to help identify acute pain.

Chronic Pain Assessment

Several validated tools assess chronic (primarily DJD) pain in cats. The Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist (Feline MiPSC) 46 is adapted into a user-friendly checklist at catredflags.com. The Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index (FMPI) from North Carolina State University 47, available at painfreecats.org, measures mobility, agility, and disposition related to chronic pain. Given that 90% of cats over 12 have DJD 48, these tools are valuable for hospice and palliative care patients.

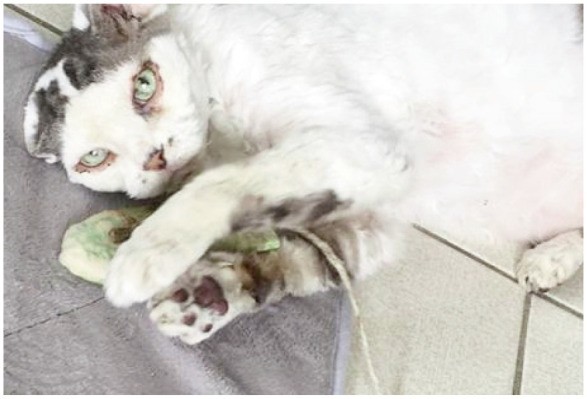

Pain Mitigation Modalities

Once pain is identified, implement a multimodal approach (Figure 3) addressing pain at multiple points in the pathway. Combining analgesics allows lower doses and reduces side effects. Complementary therapies, environmental modifications, and nutraceuticals can be part of the pain control plan. 37

Figure 3.

(a) Hospice patient with painful bleeding tumor before pain control. (b) Same patient after multimodal pain control with buprenorphine and gabapentin. Images courtesy of Clara Showalter and Katrina Breitreiter

Opioids

Opioids are common for acute pain and can manage chronic pain. 37 Pure mu (μ)-opioid agonists like morphine, hydromorphone, methadone, and fentanyl are potent for moderate to severe pain, often used during surgery. Buprenorphine, a partial μ-opioid agonist, provides mild to moderate control and has longer-acting formulations, including a transdermal option approved in 2022. Butorphanol, a mixed μ-opioid antagonist/kappa agonist, is less effective as a single analgesic but can be used for minor procedures with mild pain and is a good sedative. 38

Opioids are generally well-tolerated in cats with rare side effects like sedation, dysphoria, mydriasis, nausea, vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux, hyperthermia, bradycardia, and respiratory depression. 41 While short-acting opioids may not be ideal for home hospice care, oral transmucosal and longer-acting buprenorphine or longer-acting fentanyl (patches) can be valuable (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dosing recommendations for opioid medications in cats

| Opioid | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl (pure μ-opioid receptor agonist) | 25 μg/h transdermal patch, q72h | ✜ No veterinary product currently available ✜ Plasma concentrations are variable and therefore level of analgesia provided may vary ✜ Patches should ideally be applied 6-12 h prior to painful stimulus 49 |

| Buprenorphine (partial μ-opioid receptor agonist) | ✜ Standard 0.3 mg/ml formulation: 0.02-0.04 mg/kg IV, IM or oral transmucosally q8h ✜ Long-acting 1.8 mg/ml injectable formulation: 0.24 mg/kg SC q24h ✜ Long-acting 20 mg/ml transdermal formulation: 0.4 ml for small cats (2.6-6.6 lb/1.2-3.0 kg) or 1.0 ml for larger cats (6.6-16.5 lb/3.0-7.5 kg) q4 days | ✜ The standard formulation should not be given SC ✜ May be more effective when combined with an NSAID ✜ The transdermal formulation should be applied under veterinary supervision to avoid human exposure until 30 mins after application |

Table detailing dosage, administration routes, and considerations for Fentanyl and Buprenorphine, opioid analgesics for cats.

NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes, reducing inflammatory mediators. 38 NSAIDs are safe and effective for acute and chronic pain in cats. Side effects include anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, and gastrointestinal irritation. Minimize risks by using the lowest effective dose and avoiding concurrent steroid use. Long-term NSAID use is safe in cats with stable chronic kidney disease for DJD management. 50,51 Meloxicam and robenacoxib are approved for cats and suitable for hospice and palliative care (Table 3). While labeled for long-term use in Europe, no NSAID is labeled for long-term use in cats in the US, requiring off-label discussion with caregivers.

Table 3.

Dosing recommendations for NSAIDs in cats

| NSAID | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Meloxicam | Loading dose of 0.1 mg/kg PO once, followed by 0.05 mg/kg PO q24h | ✜ The higher labeled dose of 0.3 mg/kg SC once is more appropriate for acute postoperative pain ✜ Dosing should be based on lean body mass ✜ Minimum effective dose should be used long term ✜ Doses as low as 0.01-0.03 mg/kg may be attempted when the potential for adverse drug reactions is high |

| Robenacoxib | 1.0-2.4 mg/kg PO q24h | ✜ Drug is rapidly absorbed, persists at the site of inflammation, and is rapidly cleared from the bloodstream ✜ Dosing should be based on lean body mass ✜ Minimum effective dose should be used long term |

Table outlining dosage, administration routes, and considerations for Meloxicam and Robenacoxib, NSAIDs commonly used in feline pain management.

Monoclonal Antibody Therapy

Monoclonal antibodies are a novel pain management option. Frunevetmab, a feline-specific anti-nerve growth factor antibody (Table 4), was FDA-approved in 2022. Nerve growth factor contributes to sensitization and is elevated in painful conditions like DJD and neoplasia. Frunevetmab is safe and effective for DJD pain in cats in placebo-controlled studies. 52 Common side effects are vomiting and injection site soreness.

Adjunct Pain Control Agents

Gabapentin, pregabalin, and antidepressants can improve pain management (Table 5). Gabapentin and pregabalin are calcium channel blockers reducing neuronal excitability. They reduce distress during transport and exams and fear-anxiety during visits. 54–57 Gabapentin dose is 20 mg/kg 55,56 or 100-200 mg/cat 54 2-3 hours before transport (reduce dose by 50% in renal dysfunction 53). Pregabalin is labeled in Europe for veterinary visit/travel fear-anxiety (5 mg/kg PO 90 minutes prior 57). Research on gabapentin and pregabalin for neuropathic pain is ongoing. Amantadine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, treats central sensitization.

Table 5.

Dosing recommendations for adjunct pain medications in cats

| Adjunct pain control agent Gabapentin | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| (calcium channel blocker) | 5-10 mg/kg PO q8-12h | ✜ Utilize at least 50% dose reduction in patients with CKD 53 ✜ Targets neuropathic pain ✜ May cause sedation or ataxia ✜ Much higher doses have been reported and may be needed ✜ May reduce fear-anxiety and distress at higher doses |

| Amantadine (NMDA receptor agonist) | 3-5 mg/kg PO q12-24h | ✜ Data on safety and efficacy of long-term use in cats are lacking |

| Pregabalin (calcium channel blocker) | 1-4 mg/kg PO q12h 40 | ✜ May cause sedation and ataxia ✜ Extra-label use for neuropathic pain ✜ At the time of publication pregabalin is only licensed in Europe (for acute fear-anxiety associated with transportation and veterinary visits) ✜ Pregabalin has not been evaluated in feline hospice and palliative care patients |

Table detailing dosage, administration routes, and considerations for Gabapentin, Amantadine, and Pregabalin, adjunct pain medications for cats.

These agents are not stand-alone pain medications and should be used with other analgesics. Pre-visit gabapentin and pregabalin reduce fear-anxiety.

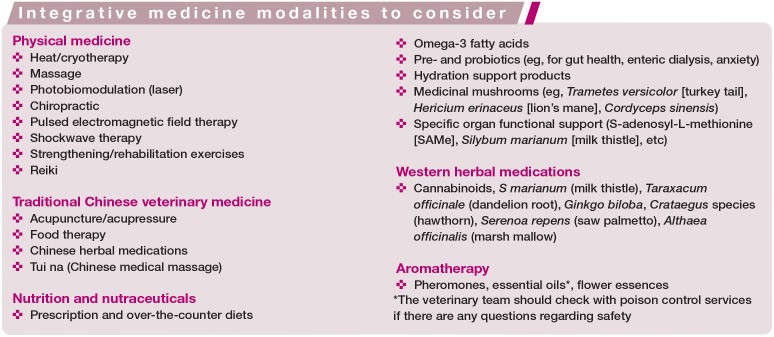

Integrative Medicine in Hospice and Palliative Care

Integrative medicine combines Western medicine with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). A 2006 veterinary oncology study showed 76% of caregivers used CAM therapies, mostly nutritional supplements. Over half expressed strong CAM interest. 58

The Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine & Health emphasizes the practitioner-patient relationship, whole-person focus, evidence-informed practices, and use of all appropriate therapies. Integrative approaches provide additional resources and tools to enhance relationships and QOL in feline hospice and palliative care. The box ‘Integrative medicine modalities to consider’ lists potential therapies. Dietary supplements lack safety/efficacy/quality control proof. Integrative medicine modalities have varying levels of scientific support in humans and animals.

Image representing integrative medicine, showing a cat receiving acupuncture, illustrating a complementary therapy approach.

Feline Emotional Health in Palliative Care Diagnosis

Emotional health is as crucial as physical health 59, and they are linked. Compromised physical health impairs emotional health, increasing fear-anxiety, pain, and frustration. 60 Pain is both sensory and emotional 61 and part of the fear-anxiety system. 59,62,63 Fear-anxiety exacerbates pain, and vice versa. 64 Minimizing threats in the cat’s environment is essential for pain management and emotional health. 37

Emotional compromise causes undesirable behaviors. 65 Inadequate environments worsen this. 66 Feline essential needs, adapted for hospice and palliative care, enhance welfare.

Components of the Cat’s Physical Environment

Cats are territorial with strong protective instincts. Hospice and palliative care patients critically need a safe physical environment.

The feline physical environment includes the home range, territory, and core territory (Figure 4). The core territory is the safe area for eating, sleeping, and playing. The territory is actively defended, and the home range is the entire roaming area. Size depends on outdoor access, cat density, and temperament. 67 In hospice and palliative care, the environment often shrinks due to impaired physical, emotional, or cognitive health. Mobility issues may limit cats to one floor or prevent vertical space use. Poor social relationships or changes in social groups further reduce the environment, sometimes to a room or closet. Outdoor cats may stay indoors.

Figure 4.

Diagram illustrating the three components of a feline physical environment: core territory, territory, and home range. Adapted from Halls (2016) 67

Environmental modifications are needed for safe outdoor access and indoor spaces where cats can be with or separated from people/pets. Safe outdoor options include supervised sun time or secure enclosures (catios, screened porches). Continued outdoor access improves QOL even with a smaller home range.

Within the home, resources for resting, feeding, scratching, and toileting should be in preferred areas, often where caregivers spend time (living room, bedroom).

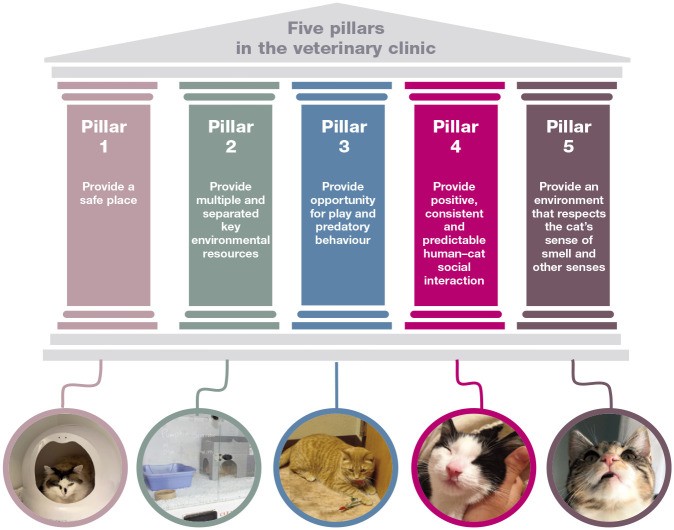

The Five Pillars of Feline Essential Needs

The ‘five pillars’ framework from the 2013 ‘AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines’ 68 identifies essential environmental needs for comfort and safety (Figure 5). They allow normal feline behaviors and minimize distress and problems. For hospice and palliative care, the framework educates caregivers on essential needs and modifications for impaired function and mobility.

Figure 5.

The Five Pillars of Feline Essential Needs, adapted from Taylor et al (2022) 66.

Cats prefer consistent and predictable environments with resources in fixed locations. Changes are needed if patients can no longer access resources (e.g., stairs). Help caregivers recognize the need for easy access to favored areas and resources, with multiple entry/exit options. Meeting environmental needs promotes positive emotions and appropriate responses to negative emotions. Example: a cat hiding from non-bonded cats. 60 Bonded cats may also have relationship breakdowns due to pain or frailty (decreased functional reserve and cognitive decline 26 Figure 6).

Figure 6.

(a) Two cats with a strong bond for over 5 years. (b) Orange tabby cat withdrawing during end-of-life, no longer wanting to be near the other cat. Images courtesy of Ilona Rodan

Veterinary teams can guide caregivers in adopting the five pillars and making modifications. Home environment questionnaires identify limitations (see supplementary material). Home visits help identify needs and educate caregivers. If not possible, photos/videos can aid planning, but adjustments may be needed.

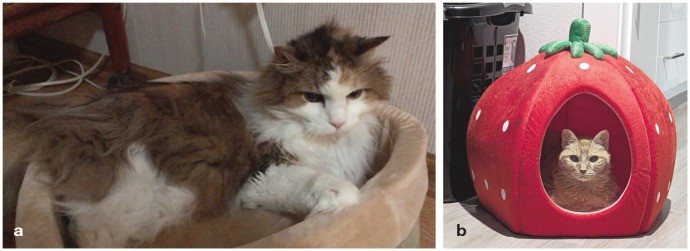

Pillar 1: Safe Place

Safe spaces are essential for territorial species, providing control, familiarity, and predictability. Feline choice is important; provide at least two resting options in different locations. Hiding options enhance coping ability, especially for compromised cats. 69–72 Good options are high-sided beds, igloo beds, carriers, or small boxes (Figure 7). Carriers with bedding left open are often readily used. Cats prefer 86-100.4°F (30-38°C). 73 Heated beds are crucial for frail patients.

Figure 7.

(a,b) Safe resting and sleeping areas provide control and predictability. Images courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b) Katrina Breitreiter

Provide safe spaces and resting areas where cats prefer to spend time, within their core territory. Ask caregivers about space use changes and ensure resource accessibility (Figure 8). If social relationship changes occur (Figure 6b), add safe spaces (minimum one per cat plus one extra).

Figure 8.

(a) Pet steps for bed access. (b) Bench for sun spot access. Images courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b) Sheilah Robertson

Hospice patients often have mobility issues like DJD and weakness. Elevated safe spaces are preferred for monitoring and safety from children/other cats. Support safe access to elevated areas with sturdy pet steps (Figure 8a) or ramps.

Educate on rest and sleep importance. Disturbed sleep impairs QOL and coping. 74–76 Cats choose when and where to rest/sleep and should not be disturbed.

Pillar 2: Multiple and Separated Key Resources

Feline resources are food, water, litter boxes, resting areas, and scratching areas. Multiple resources should be dispersed and spaced apart (few feet between). In multi-cat homes, provide approximately one resource per cat/social group to prevent competition, with visual barriers and safe access. Ensure access from two locations to prevent blocking. Educate caregivers to recognize tension signs (staring, stalking, blocking). 77 Avoid placing resources in hallways or narrow paths where tension arises.

Hospice patients need special accommodations. Place resources in their preferred environment, even if small, and separate them. If competition exists, provide multiple resources in the same area.

Pillar 1 covered safe spaces; feeding/hydration are later. Focus here is on litter boxes and scratching areas.

Litter Boxes

Place litter boxes in multiple locations, separated from each other, food, water, and resting areas. Caregivers often place boxes side-by-side in basements, which is unsuitable for frail patients. Ensure easy accessibility on all levels where the cat spends time, away from noise and pets.

Cats prefer large litter boxes (68 cm length 78) for turning, digging, and eliminating. Ensure safe entry/exit and separation from resources. Cats prefer clean boxes without solid waste. 79 Hospice patients often void larger urine volumes; scoop multiple times daily and clean thoroughly weekly.

Many hospice patients struggle to enter/exit litter boxes. Lower one lip of the box (Figure 9) – cement mixing boxes are good. For DJD cats, difficulty squatting results in urine outside the box. Dog litter boxes or storage boxes with low front and high back (Figure 9a) help. For cats unable to use any box, puppy pads can keep the area clean.

Figure 9.

(a) Low-lip litter box. (b,c) Cement mixing box and storage box as litter boxes. Images courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b,c) Heather O’Steen

See ‘AAFP and ISFM Guidelines for House-soiling’ (catvets.com/house-soiling) and ‘2021 AAFP Senior Care Guidelines’ (catvets.com/senior-care) for more information. 26,80

Scratching Posts

Scratching is normal for claw sheath removal, muscle stretching, and territory marking. Scratching behavior varies; distress increases scratching for territory marking. 81,82 Undesirable scratching may occur due to inability to use previous posts.

Scratching is important for hospice patients. Never force or punish scratching. Promote scratching in desired locations by providing options suited to their abilities. Vertical scratchers should be tall with sturdy bases. Preferred textures are sisal rope and carpet. 81,82 Cats over 14 may prefer horizontal posts due to DJD discomfort, and carpet over sisal/cardboard. 82 Place scratchers in undesirable scratching areas. See AAFP’s Claw Friendly Toolkit (catvets.com/claw-friendly-toolkit).

For cats unable to scratch, frequent nail care is needed, including trimming. Nails may thicken and grow faster. Analgesia/anxiolytics may be needed for nail trimming to prevent fear and pain. Gabapentin and pregabalin can be used, or buprenorphine with gabapentin (Tables 2 and 5). Consider veterinary/technician house calls for nail care if caregivers can’t manage it.

Pillar 3: Play and Predatory Behavior

Play

If cats still enjoy play, offer interactive play twice daily to improve satisfaction and muscle strength. Hospice patients may not actively chase toys but enjoy watching them move and interacting. Play should be one-on-one, based on energy levels (Figure 10). Some patients may prefer watching younger cats play.

Figure 10.

Cat engaging in gentle play, illustrating one-on-one interaction based on energy level. Image courtesy of Ilona Rodan

Predatory Behavior

Cats are solitary hunters and foragers, both predator and prey. Domestic cats retain strong predatory instincts. See ‘Nutrition and hydration management’ section.

Pillar 4: Positive, Consistent Human-Cat Interaction

Veterinary and caregiver interaction approaches are critical for the human-cat bond and preventing fear, anxiety, pain, and frustration. Best practices are in ‘2022 AAFP/ISFM Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines’ 65 and resources at catvets.com/interactions.

Hospice patients often desire increased human interaction, enjoying massage and grooming. Regular interaction may be needed for medication. Allow interactions in preferred locations with hiding options available. Cats prefer all four feet on a safe surface; picking them up is usually not preferred. Hospice patients may need ramps or pet steps for desired areas. For necessary movement, use a blanket/towel wrap.

Pain or declining health can alter interaction responses. Caregivers should note changes and contact the veterinary team.

Massage

Feline massage may reduce musculoskeletal and myofascial pain. 83 Most cats enjoy massage, but ensure acceptance and avoid disliked areas (belly, tail base).

Grooming

Groom unkempt or matted cats to improve comfort and hygiene. Many cats enjoy grooming attention, especially if started young. For cats unaccustomed to grooming, start with gentle stroking and soft brushes.

Don’t pull out mats manually – it’s painful. Trim mats by placing a comb between skin and fur to prevent skin cuts. For heavily matted cats, professional clipping with analgesia/sedation is ideal. Sanitary clips help with fecal/urine soiling. Use unscented baby wipes for cleaning if washing is needed.

Medication Administration

Hospice patients often need analgesia, anti-nausea medication, and other support. Ideally, introduce treats for medication before illness, but compliance is only 76% due to stress. 84 Client education is needed for easier medication and reduced distress. Medication should be positive and minimally invasive, administered calmly. Box ‘Steps to minimize distress associated with medicating cats’ provides recommendations. Cats may prefer oil-based compounded medications over water-based. 85

Figure 11.

Gelatin capsules for combining tablets, minimizing administration frequency. Image courtesy of Ilona Rodan

Address patient/caregiver QOL if medication distress and fear-anxiety become problematic. Feeding tubes are excellent for medication and nutritional support.

Pillar 5: Environment Respecting Senses

Pillar 5 originally focused on smell. The ‘2022 ISFM/AAFP Cat Friendly Environment Guidelines’ expanded it to include all senses. 66 Cats use senses to assess safety and threats.

- ✜ Olfactory: Cats have exceptional smell sensitivity. Olfactory system links to the limbic system (emotions), explaining why offensive smells cause distress, and positive smells increase positive emotions. 86 Maintain familiar scents, promote positive smells, and minimize negative ones. Heated wet food and flavor enhancers improve appetite. Avoid noxious smells like strong cleaners, perfumes, incense, smoke, scented candles (use battery-operated candles instead). Synthetic feline pheromone diffusers/sprays can help.

- ✜ Auditory: Loud noises startle cats. Provide a quiet environment without startling noises (loud voices, appliances, neighbors). Cat-specific music reduces distress and increases relaxation. 87

- ✜ Visual: Cats detect motion for prey and threats. Use slow, predictable movements. Allow cats to feel hidden if desired.

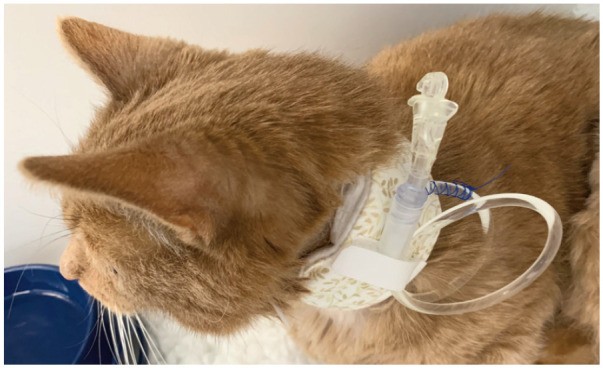

Nutrition and Hydration Management in Feline Palliative Care Diagnosis

Gastrointestinal signs (inappetence, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea) are considered in QOL assessments. Caregivers perceive QOL decline with weight loss, poor appetite, vomiting, or diarrhea. Nausea control and appetite support are vital for QOL, as are hydration and water intake.

Ensuring adequate nutrition in hospice patients is challenging. Energy and protein needs increase in cats over 11-12 years. 26,88 Illness and injury further increase energy needs. Inadequate nutrition leads to frailty, worsening QOL. 26

Never force-feed cats (syringe feeding, food on face/paws). Hospice patients are often inappetent due to illness, pain, and nausea. Forced feeding worsens food aversion, nausea, pain, and distress. Medications for illness, pain, and nausea are crucial. Feeding tubes are excellent if nutritional intake is insufficient or medication is difficult.

Use of Feeding Tubes

Feeding tubes can improve QOL and caregiver relationships, considered comfort care. They reduce stress by facilitating medication, nutrition, and fluid administration (Figure 12). Forceful medication distress outweighs medication benefits when considering QOL and the cat-caregiver bond.

Figure 12.

Esophagostomy tube covered with a padded collar, used for nutrition, fluids, and medication. Image courtesy of Sam Taylor

Esophagostomy (esophageal) feeding tubes are well-tolerated and can stay in place for weeks/months with proper care. Cats may still eat/drink voluntarily with tubes. Padded collars protect the tube and aid maintenance.

Discuss tube feeding pros and cons early. Surgical placement needs general anesthesia; consider risks. Use tubes initially for medication and hydration before nutrition. Discuss caregiver budgets, QOL/life duration balance, and care goals.

See ‘2022 ISFM Inappetent Cat Guidelines’ 89 and International Cat Care’s caregiver guide (bit.ly/aafp-feeding-tubes) for tube types, placement, and complication management.

Feeding Strategies

Cats should willingly participate in feeding and medication. Strategies include:

- ✜ Feed cats separately with visual barriers. Normal feline feeding is small, frequent meals 90, important for hospice patients with reduced stomach capacity.

- ✜ Place dishes on the floor to prevent falls. Raised dishes are better for DJD or mobility issues (Figure 13).

- ✜ Puzzle feeders, while recommended for healthy cats, may reduce caloric intake in hospice patients.

- ✜ Provide enticing, preferred food. Cats over 7 prefer warmed wet food (98.6°F/37°C) 91. Stronger smelling foods appeal to cats with smell loss. Offer options to determine preference.

- ✜ Flavor enhancers (lickable treats, tuna juice, onion-free broth) may boost appetite but avoid excessive calories.

- ✜ See International Cat Care’s caregiver guide on inappetence (bit.ly/aafp-inappetence).

Figure 13.

(a,b) Raised food and water dishes for cats with DJD and mobility issues. Images courtesy of (a) Ilona Rodan and (b) Heather O’Steen

Hydration Management

Hospice patients are at risk of dehydration. Strategies include adding warm water to food, multiple water sources (fountains, dripping faucets) separated from food, and flavor enhancers (tuna juice, low-sodium broth). Electrolyte gravy packets improve hydration. At-home subcutaneous fluids can be considered if they don’t harm QOL or the cat-caregiver bond.

Antiemetics

Cats can’t report nausea. Any vomiting or inappetent cat should receive antiemetics. Nausea signs are subtle: lip licking, hypersalivation, food aversion, burying food.

Maropitant (central antiemetic) blocks substance P. Ondansetron (5-HT3 antagonist) may be more effective for nausea. Both are generally well-tolerated (Table 6).

Table 6.

Dosing recommendations for antiemetic medications in cats

| Antiemetic | Dosing recommendations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Maropitant | 1 mg/kg IV, SC or PO q24h | ✜ Antiemetic |

| Ondansetron 92 | 0.5-1 mg/kg IV (slowly), SC, IM or PO q8h | ✜ Antiemetic and anti-nausea ✜ Subcutaneous administration may result in some cats reacting to the injection. This reaction may be mitigated by diluting ondansetron prior to injection |

Table detailing dosage, administration routes, and considerations for Maropitant and Ondansetron, antiemetic medications for cats.

Appetite Support

Mirtazapine (5-HT3 antagonist) and capromorelin (ghrelin agonist) are FDA-approved appetite stimulants. Mirataz (transdermal mirtazapine) manages weight loss. Capromorelin increases appetite in CKD-related weight loss (Table 7). See ‘2022 ISFM Inappetent Cat Guidelines’ 89 for more information.

End of Life Considerations in Feline Palliative Care Diagnosis

Following these guidelines eases the end-of-life journey. Planned and considered passing should minimize pain and ensure a peaceful transition. Veterinarians and teams provide final direct service to cat and caregiver during euthanasia. Caregivers present should be fully informed. Desire for quick, gentle death shouldn’t override caregiver time needs and team preparation.

See AAFP’s End of Life Educational Toolkit (catvets.com/end-of-life-toolkit) for resources on QOL evaluation, caregiver support, and bereavement counseling.

Conclusions

Shifting from curative to comfort care requires prioritizing QOL, guided by bioethical principles. QOL assessments determine if a cat has a life worth living. Treatment acceptance is key; respect expressed preferences. Honoring the human-animal bond involves non-maleficence (avoiding harm to the bond) and beneficence (prioritizing the bond over aggressive procedures).

Veterinary professionals improve patient welfare – physical and emotional health are intertwined. Compromised physical health impairs emotional health, increasing distress and behavior problems. Environments meeting essential physical and social needs are crucial. The five pillars framework enhances comfort and safety, enabling normal behaviors and minimizing distress.

Image symbolizing the human-animal bond in end-of-life care, showing a caregiver comforting a cat.

The human-animal bond drives the adoption of human hospice philosophies for cats. Using evidence-guided feline hospice and palliative care, including the five-step plan, veterinary professionals can meet patient and caregiver needs effectively.

Summary Points

- ✜ Bioethical obligations guide hospice and palliative care and facilitate shared decision-making for cats, caregivers, and care units.

- ✜ Hospice and palliative care encompass physiological and moral/ethical considerations, advocating for cats who cannot advocate for themselves.

- ✜ Excellent communication skills enhance caregiver and veterinary provider satisfaction.

- ✜ Pain and discomfort recognition and alleviation are paramount for QOL. Resources aid caregiver pain recognition.

- ✜ Feline essential needs, adapted for hospice care, enhance welfare. Caregivers should be educated on the five pillars and home adaptations.

- ✜ The ‘2023 AAFP/IAAHPC Feline Hospice and Palliative Care Guidelines’ offer evidence-based approaches to meet the needs of hospice patients and their caregivers.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material

sj-pdf-1-jfm-10.1177_1098612X231201683.pdf (709.9KB, pdf)

Hospice and palliative care patient questionnaire

Caregiver brochure

sj-pdf-2-jfm-10.1177_1098612X231201683.pdf (5MB, pdf)

‘Hospice and palliative care for your cat’.

Acknowledgments

These Guidelines were supported by an educational grant to the AAFP from Royal Canin. Contributions were provided by Daniel Dominguez and Heather O’Steen in the preparation of the Guidelines. The video in the supplementary material is provided courtesy of Mikel Delgado.

Footnotes

Supplementary material: The following files are available as supplementary material alongside the Guidelines:

✜ Hospice and palliative care patient questionnaire;

✜ Video – ‘Teaching your cat to get used to medication’;

✜ Caregiver brochure – ‘Hospice and palliative care for your cat’.

Ilona Rodan serves on an advisory board for Royal Canin. Members of the Task Force have also received financial remuneration for providing educational material, speaking at conferences and/or consultancy work; however, none of these activities cause any direct conflict of interest in relation to these Guidelines.

Funding: The members of the Task Force received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in JFMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals (including cadavers) and therefore informed consent was not required. For any animals or people individually identifiable within this publication, informed consent (verbal or written) for their use in the publication was obtained from the people involved.

Contributor Information

Diane R Eigner, The Cat Whispurrr, Barnegat, NJ, USA.

Katrina Breitreiter, South Austin Cat Hospital, Austin, TX, USA.

Tyler Carmack, Caring Pathways USA, Hampton Roads Veterinary Hospice, Virginia Beach, VA, USA.

Shea Cox, BluePearl Pet Hospice, Mars Veterinary Health, Temecula, CA, USA.

Robin Downing, The Downing Center for Animal Pain Management, Windsor, CO, USA.

Sheilah Robertson, Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice, Lutz, FL, USA.

Ilona Rodan, Cat Behavior Solutions, Cat Care Clinic, Madison, WI, USA.

References

[References]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material

sj-pdf-1-jfm-10.1177_1098612X231201683.pdf (709.9KB, pdf)

Hospice and palliative care patient questionnaire

Caregiver brochure

sj-pdf-2-jfm-10.1177_1098612X231201683.pdf (5MB, pdf)

‘Hospice and palliative care for your cat’.