The landscape of cancer diagnostics is continually evolving, with a significant drive towards earlier and more accessible detection methods. Among the promising advancements in this field is the development of point-of-care (POC) diagnosis kits, particularly for circulating tumor cells (CTCs). These kits hold the potential to revolutionize cancer management by enabling rapid and convenient analysis, bringing sophisticated diagnostic capabilities closer to the patient. This article explores the innovative application of lectin-based microfluidics in creating effective POC diagnosis kits for CTC cell sorting, highlighting its potential to transform early cancer detection and monitoring.

Lectin-based diagnostics are emerging as a powerful tool in biomedical research, leveraging the unique carbohydrate-binding properties of lectins. Lectins are proteins found across various organisms, from animals and plants to fungi, and are known for their ability to selectively bind to specific sugar structures, or glycans [93, 94, 95]. This specificity is crucial in diagnostic applications, particularly in identifying and isolating CTCs. CTCs, shed from primary tumors and circulating in the bloodstream, are critical biomarkers in cancer metastasis and prognosis. The surface of cancer cells, including CTCs, often exhibits altered glycosylation patterns compared to normal cells. This differential glycosylation provides a unique target for lectins to selectively capture and sort CTCs from blood samples. Lectins can distinguish subtle differences in glycan structures, including sugar residue position and anomeric configurations [100], making them highly specific probes for CTC identification. Their multivalent binding nature, with many lectins possessing multiple carbohydrate-binding domains [101], further enhances their capture efficiency.

Traditional methods for CTC detection often rely on laboratory-based immunoassays, which can be time-consuming, require specialized equipment, and are not easily adaptable for POC settings. Microfluidics offers a compelling alternative, enabling the miniaturization and automation of complex assays onto a single chip [106]. Microfluidic devices offer several advantages for POC CTC diagnosis kits, including reduced sample volume, faster analysis times, and the potential for quantitative results. Integrating lectins into microfluidic platforms creates a powerful synergy for CTC cell sorting.

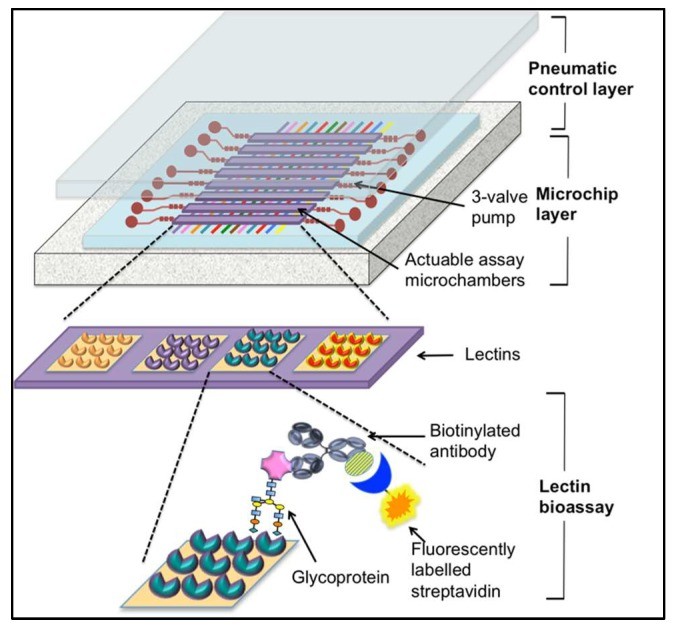

In a notable example of lectin-based microfluidic technology, Shang et al. developed an automated microfluidic barcode platform that utilized lectins and antibodies in a sandwich assay format [107]. Although this system was initially demonstrated for ovarian cancer biomarker CA125 detection, the underlying principles are directly applicable to CTC capture and sorting. The system featured microfluidic channels within a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane, incorporating micropumps and lectin-based microchambers (visualized in Figure 4). This design facilitates precise fluid control, efficient mixing within the assay chambers, and “stop-flow” fluid transport, optimizing the interaction between lectins and target glycoproteins. Glycoproteins, in the context of CTC sorting, would be the glycosylated surface proteins on CTCs. The lectin array within the microchamber serves to capture these CTCs, and detection can be achieved using antibodies and fluorescent labeling [107].

Microfluidic lectin-based barcode bioassay chip for point-of-care CTC diagnosis kit development.

Microfluidic lectin-based barcode bioassay chip for point-of-care CTC diagnosis kit development.

The application of such a microfluidic system to CTC cell sorting for POC diagnosis kits is highly promising. Imagine a POC device where a small blood sample is introduced into a microfluidic chip. Lectin arrays within the chip selectively capture CTCs based on their unique glycan profiles. The microfluidic environment ensures efficient and rapid interaction, minimizing sample and reagent volumes. Following capture, CTCs can be further analyzed within the chip, potentially for genetic or proteomic markers, providing comprehensive diagnostic information at the point of care.

The advantages of point-of-care CTC diagnosis kits are substantial. Firstly, they offer rapid turnaround times, significantly reducing the delay between sample collection and diagnostic results. This speed is critical in cancer management, where timely diagnosis can directly impact treatment decisions and patient outcomes. Secondly, POC kits enhance accessibility to advanced diagnostics, particularly in resource-limited settings or remote locations where centralized laboratories may be unavailable. The ease of use and portability of POC devices make them ideal for decentralized testing, potentially in clinics, physician’s offices, or even at home. Furthermore, POC CTC diagnosis kits can facilitate frequent monitoring of cancer progression or treatment response. Serial CTC analysis using POC devices can provide real-time insights into disease dynamics, enabling personalized treatment strategies and improving patient management.

While lectin-based microfluidic POC kits for CTC cell sorting hold immense potential, challenges remain. Ensuring high sensitivity and specificity for CTC capture and detection is paramount. Further research is needed to optimize lectin selection, microfluidic device design, and detection methods to achieve robust and reliable performance in POC settings. Clinical validation studies are essential to demonstrate the clinical utility of these kits and their impact on patient care. Moreover, regulatory approvals and integration into existing healthcare workflows are crucial steps for widespread adoption.

In conclusion, point-of-care diagnosis kits for CTC cell sorting, leveraging the specificity of lectins and the efficiency of microfluidics, represent a significant stride forward in cancer diagnostics. These innovative tools promise to democratize access to advanced cancer detection, enabling earlier diagnosis, improved monitoring, and ultimately, better patient outcomes. As research and development in this area continue to advance, lectin-based microfluidic POC kits are poised to play a transformative role in the future of cancer care, bringing rapid, convenient, and accurate diagnostic capabilities directly to the point of care.

References

[93] Vasta, G.R.; Quesenberry, M.; Ahmed, H.; O’Leary, T.J. C-type lectins and galectins mediate innate and adaptive immunity: The natural dichotomy in vertebrate humoral defense. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 897, 248–261.

[94] Van Damme, E.J.; Peumans, W.J.; Barre, A.; Rougé, P. Plant lectins: A complex blend of structures and properties. Glycobiology 2008, 18, 1037–1045.

[95] Cambi, A.; Koerkamp, M.G.; Akkerman, J.W.; Gijbels, M.J.; de Vries, C.J.; Adema, G.J.; Figdor, C.G. C-type lectin receptors: Key players in innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2005, 206, 191–203.

[96] Kawasaki, T.; Sato, R. Mannan-binding lectin and related proteins in innate immunity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1993, 1156, 240–244.

[97] Powell, F.; Tiralongo, J.; Blumbergs, P.; Liebelt, J.; Manion, J.; Tiralongo, E. Evaluation of the antiviral activity of plant lectins against a panel of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 3623–3631.

[98] Lis, H.; Sharon, N. Lectins as molecules and tools. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1986, 55, 35–67.

[99] Gabius, H.J. Animal lectins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990, 192, 367–376.

[100] Varki, A.; Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D.; Stanley, P.; Hart, G.W.; Aebi, M. Essentials of Glycobiology, 2nd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2009.

[101] Imberty, A.; Chabre, M.; Bourne, Y. C-type lectin-like domains: One motif, multiple functions. Glycobiology 2002, 12, 19R–27R.

[102] de Sanjosé, S.; Diaz, M.; Castellsagué, X.; Clifford, G.M.; Bruni, L.; Muñoz, N.; Bosch, F.X. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology, CIN I and invasive cancer. Vaccine 2007, 25 Suppl 3, C70–C73.

[103] Shapiro, J.A.; Ko, D.; Dryer, P.; Sepe, P.; Warshawsky, P.; Gilbert, L.; Ringer, B.; Sharma, S.; Inhorn, S.L. Compliance with annual Papanicolaou smear screening: A community-based study. J. Fam. Pract. 1991, 32, 629–633.

[104] Pao, C.C.; Lin, S.S.; Chang, Y.C.; Wu, M.F.; Tsai, S.L.; Hsieh, C.H.; Twu, N.F.; Chang, T.C.; Wong, T.Y.; Soong, Y.K.; et al. Antibody response to human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles in patients with cervical carcinoma and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 2777–2781.

[105] Muñoz, N.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S.; Herrero, R.; Castellsagué, X.; Shah, K.V.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J.; International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicentric Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 510–519.

[106] Whitesides, G.M. The ‘right’ size in nanobiotechnology. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 91–94.

[107] Shang, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.;лары, W.; Zhao, Y. Microfluidic barcode chip for automated multianalyte immunoassay with high sensitivity and throughput. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22352.