Introduction

Infectious diseases, triggered by pathogenic microorganisms, pose a significant threat to global public health and economic stability due to their transmissibility across individuals and populations. The urgent need for efficient diagnostic tools is paramount to enable prompt and accurate identification of cases, interrupt transmission pathways, and facilitate timely administration of appropriate treatments. Point-of-care (POC) tests, delivering actionable results swiftly and near the patient, serve as a crucial “personal radar” in this fight. This review delves into the clinical demands for POC testing across several critical pathogens, including malaria parasites, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papillomavirus (HPV), dengue, Ebola and Zika viruses, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB). We will compare various molecular strategies employed in POC tests, encompassing pathogen nucleic acid and protein detection, circulating microRNA analysis, and antibody assays. Furthermore, we will explore recent advancements in innovative POC technologies, with a spotlight on microfluidic and plasmonic-based approaches, highlighting their potential to transform infectious disease diagnostics at the point of care.

Infectious diseases, predominantly caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi, stand out from other illnesses due to their capacity for rapid, exponential transmission within populations. This characteristic renders them a persistent danger to public health infrastructure and global economies. Estimates suggest that over half of the global population is susceptible to infectious diseases, marking them as a leading threat to humanity[1].

The adage, “Without diagnostics, medicine is blind,”[2] underscores the foundational role of accurate diagnosis in effective healthcare delivery. Appropriate and timely treatment hinges upon precise diagnosis. Sensitive, specific, and rapid diagnostic testing is not only essential for guiding effective treatment strategies but also plays a vital role in curbing the spread of infectious diseases. While central clinical laboratories offer sophisticated and precise assays, including blood culture, high-throughput immunoassays, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and mass spectrometry (MS) tests, these methods are often characterized by their time-consuming nature, labor intensity, high costs, and reliance on complex instrumentation and specialized personnel. Conversely, point-of-care (POC) tests provide swift, ‘on-site’ results directly at the point of healthcare delivery, which is particularly beneficial in resource-constrained environments, facilitating prompt and appropriate treatment [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has outlined “ASSURED” criteria for POC tests aimed at addressing infectious disease control, especially in developing nations: (1) Affordable, (2) Sensitive, (3) Specific, (4) User-friendly, (5) Rapid and robust, (6) Equipment-free, and (7) Deliverable to end-users [4].

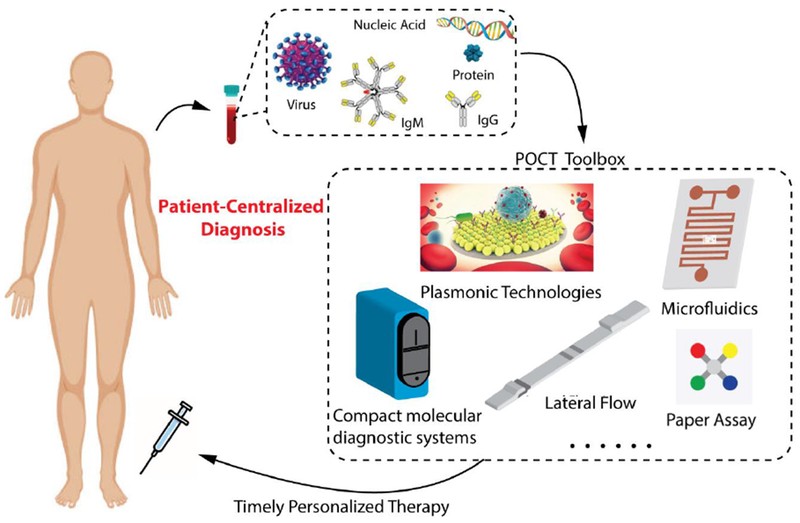

This review examines studies published within the last decade, indexed in PubMed, focusing on the advancement of POC tests for infectious diseases. Based on the volume of research in this domain, we have selected to concentrate on significant infectious disease-causing microorganisms such as malaria parasites, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papillomavirus (HPV), dengue, Ebola and Zika viruses, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) bacteria. Initially, we will discuss the pathophysiology, public health implications, and the need for point of care diagnosis for these microorganisms. Then we will focus on key biomarkers utilized in POC tests, including pathogen nucleic acids, proteins, circulating microRNAs, and antibodies, comparing their significance throughout the disease management continuum. Finally, we will review advancements in microfluidics and plasmonics, two technologies that have demonstrated remarkable progress in the development of POC tests for infectious diseases over the past decade. These technologies, along with others in the “POCT Toolbox” (Figure 1), act as a personal radar in the ongoing battle against infectious diseases, moving towards patient-centered diagnosis and treatment, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Point of Care Tests (POCT) Toolbox for Infectious Disease Diagnosis

Point of Care Tests (POCT), encompassing compact molecular diagnostic systems, lateral flow assays, microfluidics, plasmonic technologies, and paper-based assays, are designed to detect a wide array of biomarkers related to infectious diseases. These biomarkers include virus particles, nucleic acids, proteins, and antibodies, serving as the cornerstone for patient-centered diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. Adapted from [5] with permission.

Pathogen Detection Needs at the Point of Care

Malaria Parasites: Rapid Diagnosis for Effective Management

Malaria affects over 300 million individuals annually, primarily in tropical regions like sub-Saharan Africa [6, 7]. The World Health Organization’s “Malaria case management: operations manual” emphasizes that effective malaria management hinges on early diagnosis and prompt artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) [8]. The microscopic detection of malaria parasites in human blood, first achieved in the 1880s [9], established Giemsa-stained blood film microscopy as the diagnostic gold standard. However, this method requires highly skilled operators and reliable equipment [10], which are often scarce in malaria-endemic regions [11]. To overcome these limitations, the past decade has seen substantial progress in developing malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs). The goal is to provide rapid and dependable testing in remote settings where conventional clinical diagnostic resources are lacking [11–14]. For instance, RDT lateral flow strips have been developed to detect malaria parasite proteins in blood, producing easily interpretable visual results [9]. Furthermore, researchers have utilized microfluidic channels to simulate capillary environments, enhancing the accuracy of malaria diagnosis in field conditions [15]. These advancements in point of care diagnosis for malaria are crucial for improving patient outcomes and controlling disease spread.

HIV: Early Detection and Monitoring at the Point of Care

Globally, over 40 million people are living with HIV, with approximately 85% residing in developing countries where access to clinical diagnostics and antiretroviral therapy (ART) monitoring is limited [4]. HIV infection leads to a spectrum of immune system disorders [16], with CD4+ T-lymphocytes identified as primary host cells [17]. The HIV virus’s gp120 envelope glycoprotein initiates infection by binding to the CD4 receptor, causing cellular damage. In the early stages of HIV infection, CD4+T cell counts diminish, compromising the immune system and increasing susceptibility to opportunistic infections [18]. While a definitive cure for late-stage AIDS remains elusive, antiretroviral drugs have proven effective in managing symptom onset [19], with greater efficacy observed in earlier infection stages [20]. Early HIV detection is also critical for preventing unwitting transmission, highlighting the importance of early point of care diagnosis. Fourth-generation p24 antigen (Ag)/antibody (Ab) combination enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) have significantly reduced the diagnostic window to within two weeks post-transmission [21]. FDA-approved fourth-generation HIV-Ag/Ab assays include ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab EIA (Abbott Laboratories) and GS HIV combo Ag/Ab EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research) [22, 23]. Commercial HIV Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs), such as Determine HIV 1/2 (Alere) and OraQuick Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test (OraSure Technologies), are available for POC antibody detection and differentiation between HIV-1/2 [24]. For therapy monitoring, CD4+T-lymphocyte enumeration and HIV viral load quantification are crucial, as CD4+ counts decline with HIV infection and recover with effective ART [25]. However, conventional methods like flow cytometry EIAs and quantitative RT-PCR face limitations in resource-limited settings due to long turnaround times, complex equipment, skilled personnel needs, and high costs [28]. The WHO emphasizes the urgent need for POC devices for accurate HIV detection and monitoring in these settings [29]. Ideal POC devices for HIV point of care diagnosis should be accurate, affordable, user-friendly, and disposable, enabling HIV infection detection and monitoring of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and HIV viral load in resource-scarce environments[30, 31]. Clinically, these devices should achieve a lower detection limit of at least 200 CD4+ cells per μL and 400 HIV copies per mL of whole blood [9].

HPV: Point of Care Testing for Cervical Cancer Prevention

Cervical cancer claims over 50,000 women’s lives annually in Africa. In the United States, before widespread Papanicolaou (Pap)-based screening, cervical cancer incidence was significantly higher. The introduction of Pap-based screening and treatment of precancerous lesions dramatically decreased incidence rates [32, 33], demonstrating the critical role of screening and early detection in cervical cancer prevention. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), caused by persistent infection with oncogenic HPV types [34], is the focus of cervical cancer screening. HPV DNA testing and/or Pap cytology, followed by colposcopy and biopsy, are standard screening methods in developed countries. Studies in India have shown that a single round of HPV DNA testing in women over 30 can significantly reduce advanced cervical cancer incidence and mortality [35]. However, these tests require sophisticated laboratory infrastructure and reliable follow-up systems, making them unsuitable for large-scale deployment in resource-limited settings, which bear 85% of the global cervical cancer burden [36, 37]. Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), recommended by the WHO for resource-poor areas [37], offers immediate results at low cost but lacks sensitivity, is operator-dependent, and lacks objective quality assurance [38, 39]. Therefore, simple, affordable POC HPV tests with high sensitivity and specificity are urgently needed to improve cervical cancer prevention through point of care diagnosis in developing countries.

Dengue and Ebola Viruses: Rapid Point of Care Diagnosis in Outbreak Scenarios

Dengue virus (DENV), with four serotypes (DENV1–DENV4), threatens approximately 3 billion people across over 120 countries [40]. Belonging to the Flaviviridae family [41], DENV is mosquito-borne and prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions of Latin America and Asia [42]. It is the most common mosquito-borne viral infection, with an estimated 390 million new infections annually [40, 43]. DENV infections can range from dengue fever to severe dengue shock syndrome [43]. The 2009 WHO classification includes dengue, dengue with warning signs, and severe dengue [45]. Currently, there are no FDA-approved vaccines or specific antiviral treatments for dengue, with one vaccine, Dengvaxia, limited to individuals with prior DENV infections [46]. Accurate and rapid DENV detection is crucial for timely management of severe cases and preventing overtreatment of non-dengue cases. Central laboratory diagnostics for DENV include virus isolation, nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) antigen immunoassays, RT-PCR, and serological antibody detection [46]. RT-PCR is considered the gold standard due to its sensitivity and specificity [47], but it is limited by its requirement for expensive equipment and specialized personnel, hindering its use in remote areas. Simple, rapid, accurate, and affordable POC tests for DENV are in high demand for timely on-site confirmation of suspected cases, facilitating effective point of care diagnosis.

Dengue fever symptoms can resemble those of other viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola virus (EBOV) infections [48]. EBOV, a highly lethal virus [49], was first identified in 1976 [48]. The Zaire species of EBOV caused a major outbreak in West Africa from 2014 to 2016, resulting in over 11,000 deaths [49, 50]. During outbreaks, EBOV detection primarily relies on RT-PCR [51]. Despite RT-PCR’s high sensitivity and specificity, its dependence on laboratory infrastructure and trained operators limits its utility in outbreak zones. Diagnostic limitations during the 2014-16 outbreak meant confirmed Ebola diagnosis was achieved in less than 60% of cases [52], underscoring the critical need for POC diagnostic tools in Ebola outbreaks [53]. Studies have evaluated rapid antigen tests for EBOV in field settings, demonstrating high sensitivity compared to RT-PCR [54]. Furthermore, lateral flow POC tests for Sudan virus have been developed, integrated with smartphone applications for data collection [55]. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy nanoparticle tags (SERS nanotags) have also been used to create rapid POC tests capable of differentiating Ebola from other febrile illnesses like Lassa fever and malaria [51]. The rapid and accurate nature of these tests is vital for effective point of care diagnosis in managing outbreaks.

Given the high contagiousness and rapid progression of diseases like Ebola, POC testing within or near containment facilities is also essential in well-resourced countries [56]. Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are available for infection prevention and control during sample handling and testing [57], and real-world laboratory experiences have been reported by U.S. institutions [58, 59]. These practical considerations are crucial when selecting and implementing POC technologies in patient care workflows, especially for point of care diagnosis in high-risk situations.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Point of Care Diagnostics to Combat a Global Epidemic

The World Health Organization estimated 10.4 million new cases of Tuberculosis (TB) in 2016, with less than 64% diagnosed [2], hindering timely treatment interventions [60]. Consequently, despite being treatable, TB remains the leading infectious cause of death globally [2], accounting for approximately 1.3 million deaths annually [4]. Achieving the End TB strategy goals of a 90% reduction in incidence and 95% reduction in mortality by 2035 [61] necessitates improved TB diagnostic tools for timely therapeutic interventions through effective point of care diagnosis. Current standard TB diagnostics, including QuantiFERON-TB, liquid culture, and smear microscopy [62], often require expensive equipment, skilled personnel, and significant sample volumes [63]. Accurate and rapid POC diagnostics are crucial for realizing the End TB strategy. Recent years have witnessed significant advancements in TB POC diagnostics. In 2010, the WHO endorsed the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay, a cartridge-based integrated miniature PCR system, for use in TB-endemic countries [64]. The Xpert® MTB/RIF assay provides results from unprocessed sputum samples within 90 minutes with minimal technical expertise [65]. WHO-endorsed tools like urine lateral flow lipoarabinomannan (LF-LAM) and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (TB-LAMP) have also been developed, eliminating the need for complex instruments, further enhancing point of care diagnosis capabilities.

Zika Virus: Point of Care Detection for Public Health Management

Zika virus (ZIKV), a mosquito-borne flavivirus, emerged in Brazil in 2015 and rapidly spread across tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas [66–68]. ZIKV infection has been linked to congenital microcephaly, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS)[69], and other severe neurological conditions in newborns of infected mothers [70]. Economic models estimate substantial costs associated with ZIKV outbreaks, including direct medical expenses and productivity losses [71]. ZIKV transmission primarily occurs via mosquitoes, with additional routes including sexual and perinatal transmission and blood transfusions [72]. Given that ZIKV infection symptoms are similar to many other febrile illnesses [68], accurate and rapid ZIKV detection is essential for appropriate and timely interventions. ZIKV point of care diagnosis is also critical for tracking infection spread, managing risks during pregnancy, monitoring treatment and vaccine efficacy, ensuring blood supply safety, and determining infection status in sexual partners [72]. The FDA has authorized emergency use of tests like the IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA) and Trioplex rRT-PCR laboratory test for ZIKV detection [73]. However, these assays require central lab facilities. Simple, accurate, and rapid POC diagnostic tools for ZIKV detection are key to effective treatment and prevention, facilitating crucial point of care diagnosis [74, 75].

Biomarkers in Infectious Disease Point of Care Testing

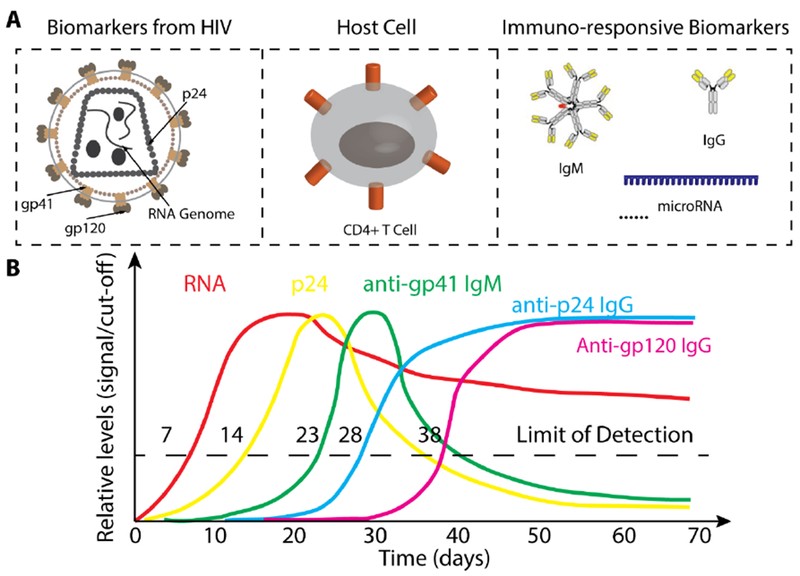

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines a biomarker as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention”[76]. In infectious diseases, a wide range of molecules and cells involved in the infection process can serve as biomarkers, including proteins, nucleic acids, and antibodies. For instance, during HIV infection, HIV RNA genome levels, capsid protein p24, and various antibodies exhibit distinct profiles that can be used to assess infection stages, as illustrated in Figure 2. The following section will review different biomarkers used in POC tests for infectious diseases and their roles in disease stage assessment and treatment monitoring, highlighting their importance in point of care diagnosis.

Figure 2. Biomarkers for HIV Infection Diagnosis and Monitoring

(A) A range of biomarkers is utilized for the diagnosis and monitoring of HIV infection. (B) This graph illustrates the kinetics of various biomarkers throughout the course of HIV infection. For detailed information, please refer to reference [77]. Adapted from [77].

Pathogen Nucleic Acids: Direct Detection of Infection

Pathogen nucleic acids, either RNA or DNA, are inherent biomarkers for infectious disease diagnosis, as nearly all infectious diseases are caused by pathogens carrying nucleic acids. Nucleic acid tests (NATs) targeting pathogen-specific nucleic acid sequences are widely used in central laboratories [78, 79]. The quantity of pathogen genome nucleic acids directly correlates with pathogen load during infection. For example, quantitative RNA detection is used to monitor HIV viral load in early infection and post-treatment [77], as shown in Figure 2. However, using pathogen nucleic acids as biomarkers may not distinguish between active infection and colonization. Traditional PCR-based NATs also require complex sample preparation and expensive thermocyclers, making them unsuitable for POC settings [80]. Significant efforts have been made to develop accurate, simple, and cost-effective POC tools for detecting infectious disease-specific nucleic acids. Strategies include replacing PCR with isothermal amplification methods like recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), simplifying procedures with microfluidic devices, and employing synthetic biology approaches. Recent advancements in POC nucleic acid detection methods are comprehensively reviewed in Maffert et al. [80], showcasing the progress in point of care diagnosis using nucleic acid biomarkers.

Antibodies: Serological Markers for Infection Status

The presence of anti-pathogen antibodies serves as a valuable biomarker for assessing infectious state. During infection, the immune system generates a substantial antibody response, often reaching levels higher than pathogen concentrations. Antibody levels can remain elevated throughout the infection, while antigen levels may decrease in later stages. For example, in late-stage HIV infection, anti-p24 antibodies remain detectable even when p24 antigen levels become undetectable [77], as shown in Figure 2. In such cases, antibodies are more diagnostically useful. Immunoassays for antibody detection are often technologically simpler to develop than antigen assays, which require costly antibody generation and preparation. HIV antibody tests, for example, can readily detect antibodies at mg/mL levels with high specificity, achieving significant success in HIV diagnosis [81, 82]. However, antibody tests are not always suitable for point of care diagnosis. For instance, maternal antibodies in infants can lead to false positives in HIV antibody tests [83, 84], and individuals before seroconversion or with atypical antibody responses may test negative despite infection [85–87].

Pathogen Proteins: Antigen Detection for Early Diagnosis

All pathogens causing infectious diseases express proteins, such as capsid and envelope proteins, which can serve as crucial biomarkers for infectious disease diagnosis. For instance, the HIV capsid protein p24 has been recognized as a potential biomarker alternative to HIV antibodies, which dominate the HIV POC testing market [77, 88]. P24, encoded by the gag gene, is present early in HIV infection and can be detected before seroconversion. The Alere Determine™ HIV-1/2 AG/AB Combo rapid test, which detects both HIV-1/2 antibodies and HIV-1 p24 antigen, is FDA-approved and CLIA-waived for fingerstick whole blood testing [90]. Unlike nucleic acids, proteins are not easily amplified, making p24 detection generally later than RNA detection in HIV infection [77], as shown in Figure 2. Nonetheless, pathogen protein detection remains a vital approach for point of care diagnosis, particularly for early infection identification.

Circulating microRNAs: Novel Biomarkers for Disease Monitoring

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules (~20 nt) that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally [91–93]. They play critical roles in host immune response during infection [96–98] and are released into extracellular environments, especially by immune cells [99, 100], acting as messengers in cell-to-cell communication [101]. Circulating miRNAs in plasma [102] and serum [103, 104] were first reported in 2008. Extracellular miRNAs are remarkably stable in body fluids, protected by RNA-binding proteins and lipid vesicles [105, 106]. While their exact functions are still being investigated, circulating miRNA expression signatures show promise as biomarkers for monitoring pathological states. For example, miRNA microarray analysis has identified differentially expressed miRNAs in serum samples from TB patients, with miR-93* and miR-29a upregulated in TB cases [107]. Plasma miRNA pairs have also been identified as potential biomarkers for HIV-associated neurological disorders (HAND) [108]. These findings suggest that circulating miRNAs could offer new avenues for point of care diagnosis and disease monitoring.

Technology Advancements in Infectious Disease Point of Care Testing

The past decade has witnessed significant technological advancements in the development of POC tests for infectious disease diagnosis. These include compact molecular diagnostic systems, lateral flow assays, microfluidics, plasmonic technologies, and paper-based assays. Microfluidics is particularly promising, offering miniaturization and integration of laboratory diagnostic modules into portable chips [109]. Plasmonic technologies, including surface plasmon resonance (SPR), localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), offer high sensitivity, label-free, and real-time monitoring capabilities, making them ideal readout modules for POC tests. The integration of plasmonics and microfluidics holds great potential for creating inexpensive, robust, and portable POC diagnostic platforms for infectious diseases [5]. The following sections will explore recent technological advancements in microfluidics and plasmonics for infectious disease point of care diagnosis. Compact molecular diagnostic systems are not covered here but are reviewed in detail elsewhere [110, 111].

Microfluidics: Miniaturizing Diagnostics for Point of Care Applications

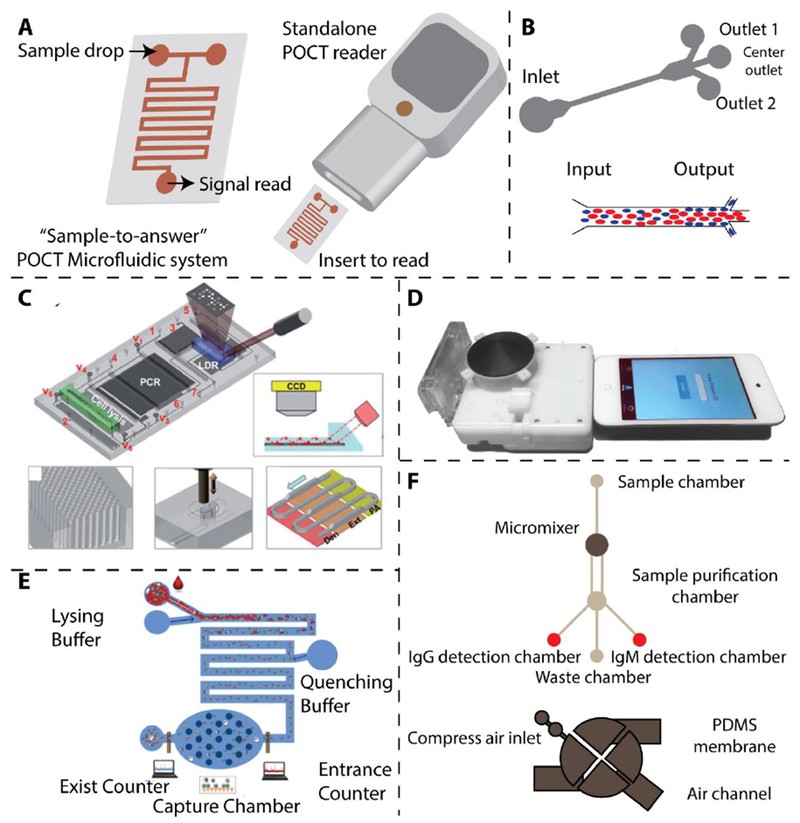

Microfluidics manipulates minute fluid volumes (10−9 to 10−18 L) [112], enabling precise spatial and temporal control of fluids [113]. This technology allows for controlled transport, mixing, and reaction of samples and reagents within micro-chambers [112, 114], making it an ideal platform for POC test development due to its automation, integration, and miniaturization capabilities [115, 116]. An ideal microfluidic system for POC testing, featuring “sample-to-answer” functionality [109], is illustrated in Figure 3A. Recent advancements in microfluidics for infectious disease POC testing are discussed below, highlighting their role in advancing point of care diagnosis.

Figure 3. Microfluidic Systems for Point of Care Infectious Disease Diagnosis

(A) Schematic representation of an ideal microfluidic system for POCT, demonstrating “Sample-to-answer” capability [109]. (B) Working principle of a microfluidic device for separating malaria-infected red blood cells (iRBCs) based on margination. Less deformable iRBCs concentrate towards the microfluidic channel’s periphery [118]. (C) An integrated microfluidic chip designed for sensitive DNA detection from M. tuberculosis, incorporating on-chip PCR [120]. Reproduced with permission. (D) Microfluidic dongle for sensitive HIV detection [122]. Reproduced with permission. (E) Microfluidic device for sensitive HIV detection using electrical impedance measurement [123]. Reproduced with permission. (F) Magnetic microbeads-assisted microfluidic device for sensitive anti-dengue antibody detection [124]. See references [4, 122] for more details.

During malaria infection, infected red blood cells (iRBCs) become less deformable as parasites mature [117]. Hou et al. utilized this property to develop a microfluidic device to assess deformability as a biomarker for malaria infection stages (Figure 3B) [118, 119]. They observed that less deformable iRBCs tend to migrate towards microchannel walls. By incorporating side channels, they isolated over 80% of iRBCs in trophozoite/schizont stages. However, the assay’s specificity requires improvement as RBC deformability changes occur in other conditions like sickle cell anemia. Wang et al. developed an automated microfluidic device for detecting single-base variations in multi-drug resistant M. tuberculosis, integrating cell lysis, DNA isolation, PCR amplification, and signal readout in a compact cartridge (Figure 3C) [120]. Micropillar arrays in microchannels enhanced DNA adsorption and colorimetric signal readout. The Sia group at Columbia University created a POC microfluidic chip for simultaneous HIV and syphilis detection using silver-enhanced immunoassays [121]. They used air bubbles to separate reagents and silver reduction to amplify colorimetric signals, achieving ELISA-like sensitivity and specificity within 20 minutes. They further integrated this device into a small cartridge readable by mobile devices like iPod Touch (Figure 3D) [122]. Watkins et al. designed a microfluidic chip for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counting for HIV monitoring using differential electrical impedance measurement (Figure 3E) [123]. This device detects impedance spikes as target lymphocytes pass through specific channel areas, completing counts within 20 minutes with results comparable to flow cytometry. Lee et al. developed an integrated microfluidic device for sensitive DENV diagnosis by detecting specific IgG and IgM antibodies (Figure 3F) [124]. They used magnetic microbeads and micromixers for efficient antibody capture and on-chip magnetic coils for antibody purification and fluorescence readout, showcasing the versatility of microfluidics for point of care diagnosis.

Paper-based microfluidics offers a low-cost, user-friendly approach for infectious disease detection in POC settings [125–128]. Colorimetric readout capabilities make them particularly useful in resource-limited environments. Whitesides et al. demonstrated a microfluidic paper-based analytical device (μPAD) for detecting antibodies to the HIV-1 envelope antigen gp41 [125]. This test is simple, rapid (within 1 hour), and requires small sample volumes (1-10 μl). Other microfluidic and paper-based methods for infectious disease detection have been developed [126–128]. Table 1 summarizes representative microfluidic technologies for point of care testing.

Table 1. Microfluidic and Plasmonic POCT Technologies for Infectious Diseases

| POCT | Pathogen | Analyte | Detection Method | Limit of Detection | Assay time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic device (non-paper-based) | Malaria | Red blood cell | Deformation | N/A | N/A | [118] |

| Malaria | Red blood cell | Deformation | N/A | N/A | [119] | |

| M. tuberculosis | DNA | Colorimetric | 50 cells/ml | N/A | [144] | |

| HIV | Antibody | Colorimetric | N/A | 20 min | [145] | |

| HIV | Antibody | Optical | N/A | 15 min | [122] | |

| HIV | CD4 and CD8 T cell | Electricity | 12 cells/μl | 20 min | [123] | |

| Dengue | IgG and IgM antibodies | Fluorescence | 21 pg | 30 min | [124] | |

| Microfluidic device (Paper-based) | HIV | HIV-1 gp41 | Colorimetric | N/A | 51 min | [125] |

| Ebola | Viral RNA | Colorimetric | 107 copy/ml | 20 min | [126] | |

| TB | TB-DNA | Colorimetric | 1.95×10−2 ng/ml | 60 min | [127] | |

| ZIKA | Viral RNA | Colorimetric | 1 copy/μl | 15 min | [128] | |

| Plasmonic Technology | HIV | A, B, C, D, E, G and panel subtypes | LSPR | 98±39 copies/ml for HIV subtype D | 1h for capture and 10 min for detection and analysis | [138] |

| Ebola | VSV glycoprotein | LSPR | 106 PFU/ml | More than 90 min | [146] | |

| TB | TB-DNA | Colorimetric | 10 μg/ml | Less than 2h | [147] | |

| ZIKA | Viral RNA | Fluorescence | 1.7 copy/ml | 3 min | [148] |

Plaque-forming units: PFU

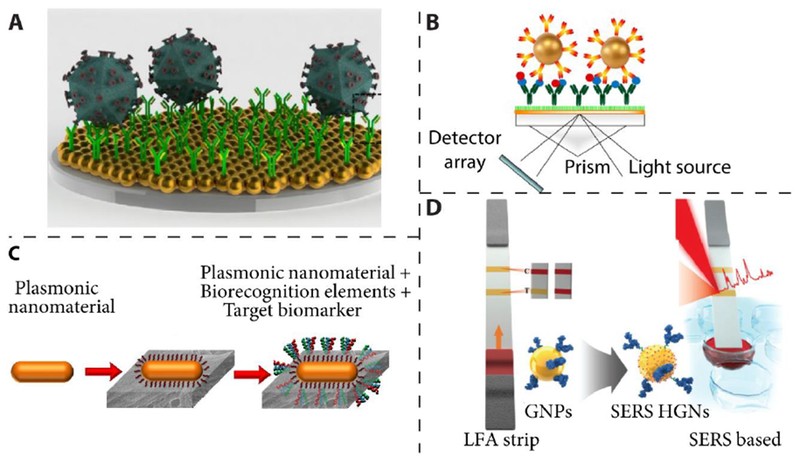

Plasmonic Technologies: High-Sensitivity Detection for Point of Care Diagnostics

Plasmonics studies the interaction of light with conductive electrons in metallic nanomaterials [129], commonly gold, silver, and aluminum [129, 130]. Plasmonic nanomaterials are used in POC applications due to their label-free nature, optical tunability, and sensitivity to surrounding media [131, 132]. For instance, phage-induced gold nanoparticle aggregation has been used in coulometric POC tests for bacterial pathogen detection [133]. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) properties of plasmonic nanomaterials are highly promising for chemical and biological sensing and clinical diagnostics [134–137]. Plasmonic sensors leverage SPR sensitivity to changes in the dielectric properties of the surrounding medium and electromagnetic field enhancement near noble metal nanostructures. Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) sensors are two important classes. LSPR sensors rely on the refractive index sensitivity of plasmonic nanomaterials [129]. LSPR has been used for label-free, fluorescence-free, repeatable HIV viral load detection in unprocessed whole blood (Figure 4A) [138]. This platform detects biomarker binding events through LSPR wavelength shifts, enabling highly sensitive, specific detection and quantification of multiple HIV subtypes with short assay times. Prism coupling SPR configurations have also been used for label-free clinical protein detection (Figure 4B) [139], monitoring biological sample capture via refractive index changes.

Figure 4. Plasmonic Technologies for Point of Care Biosensing

(A) Illustration of a nanoplasmonic viral load platform for detecting intact viruses. Reproduced with permission from [138]. (B) Schematic of an SPR-based protein sandwich assay. Reproduced with permission from [139]. (C) Schematic representing an LSPR-based biosensor with peptide recognition elements. Reproduced with permission from [141]. (D) Illustration of a SERS-based lateral flow assay configuration for detecting staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Reproduced with permission from [143].

Paper-based devices offer advantages like high surface area, small sample volume needs, portability, flexibility, and low cost [140]. Plasmonic paper LSPR devices have been shown for selective and sensitive protein biomarker detection (Figure 4C), making them suitable for POC infectious disease diagnosis in resource-limited settings [141]. SERS involves significant Raman scattering amplification from analytes adsorbed on nanostructured metal surfaces [142]. SERS-based lateral flow assays have been developed for staphylococcal enterotoxin B detection with ultrahigh sensitivity compared to ELISA (Figure 4D) [143]. Table 1 includes representative plasmonic technologies for point of care testing, showcasing their potential for advanced point of care diagnosis.

Conclusions and Outlook

In conclusion, point of care tests, with their simplicity, rapid turnaround, and broad accessibility, are crucial for prompt infectious disease diagnosis, particularly in resource-limited settings. This enables timely and effective patient-centered treatment and management. While various biomarkers have been successfully utilized in POC tests, there is a continuing need for biomarkers with enhanced sensitivity and specificity to improve point of care diagnosis. Systematic characterization of biomarker signatures for individual infectious diseases may be a valuable approach for future biomarker screening. Given the overlapping clinical symptoms of many infectious diseases, multiplex POC tests are highly desirable. Significant technological progress has been made in POC infectious disease testing, especially in microfluidics and plasmonics. However, rigorous clinical validation is essential for translating these technologies from research to clinical practice for effective point of care diagnosis. Practical considerations, including infection control, testing in confined environments, IT connectivity, and clinical pathway optimization, are also vital for successful implementation to address clinical challenges [149].

Highlights

- POCT is essential for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of infectious diseases.

- Simple, accurate, multiplex, and accessible POC tests are needed for major pathogens.

- POCT technologies, including microfluidics and plasmonics, have advanced significantly.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge NIH RO1DA035868, Penn Center for Precision Medicine, and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania for funding support.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.