Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is a chronic condition affecting multiple systems in the body, primarily recognized by an abnormal increase in heart rate upon standing, known as orthostatic tachycardia. Patients with POTS experience orthostatic intolerance, meaning their symptoms worsen when upright and improve when lying down. This condition disproportionately affects girls and women, often starting around puberty and continuing into early adulthood. The impact of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome can be significant, leading to considerable functional impairment that frequently hinders work or school attendance. Fortunately, various treatments are available to alleviate POTS symptoms and improve functionality, and these can be initiated within primary care settings.

The hallmark of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is an elevated heart rate upon standing without a corresponding drop in blood pressure. Individuals often describe dizziness and heart palpitations when in an upright position, especially when standing still, occasionally leading to fainting (syncope). This syndrome can severely diminish a patient’s quality of life and functional capacity, potentially causing significant economic strain.1–3 POTS is more prevalent among girls and young women and has been linked to other conditions such as migraines and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.4 This article will delve into the diagnosis of POTS, explore conditions that should be considered in a differential diagnosis, discuss associated disorders, and outline both medication-based and non-medication-based strategies for managing patients with POTS, drawing from original research, narrative reviews, and established consensus statements (Box 1).

Box 1: Evidence Base for This Review

This review is informed by recent position statements regarding the investigation and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). These include the 2011 American Autonomic Society Consensus Statement, the 2015 Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Statement, and the 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement. For articles detailing specific mechanisms and treatments, we conducted a MEDLINE search up to July 2021, utilizing terms such as “POTS,” “postural tachycardia syndrome,” and “postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.” Our primary focus was on original research articles, but we also considered review articles. Furthermore, we examined the reference lists of pertinent articles to identify additional relevant studies.

Defining POTS: What Are the Diagnostic Criteria?

Several professional organizations in North America have established consensus criteria for diagnosing POTS. These include the American Autonomic Society,6 the Heart Rhythm Society,7 the Canadian Cardiovascular Society,5 and most recently, a POTS Working Group convened by the United States National Institutes of Health.8 These consensus statements consistently emphasize the need for both orthostatic tachycardia and symptomatic orthostatic intolerance to be chronic and co-occurring issues. The specific criteria for a Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome Diagnosis are detailed in Box 2. Symptoms must arise after standing, accompanied by a significant increase in heart rate, but without a substantial decrease in blood pressure. It’s crucial to rule out other conditions that could explain the orthostatic tachycardia before diagnosing POTS. These conditions include anemia, anxiety, fever, pain, infection, dehydration, hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, prolonged periods of inactivity, or the use of medications known to elevate heart rate (such as stimulants, diuretics, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors).9 The presence of such conditions would preclude a diagnosis of POTS.

Box 2: Diagnostic Criteria for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

All of the following criteria must be fulfilled for a diagnosis of POTS:

- A sustained increase in heart rate of ≥ 30 beats per minute (bpm), or ≥ 40 bpm for individuals aged 12–19 years, occurring within 10 minutes of assuming an upright posture.

- Absence of significant orthostatic hypotension, defined as a blood pressure drop ≥ 20/10 mm Hg.

- Frequent experience of orthostatic intolerance symptoms, which are exacerbated in the upright position and rapidly improve upon returning to a supine position. These symptoms can vary but commonly include lightheadedness, palpitations, tremors, generalized weakness, blurred vision, and fatigue.

- Symptom duration of 3 months or longer.

- Exclusion of other conditions that could explain sinus tachycardia (Box 3).

While the diagnostic criteria for orthostatic tachycardia in POTS require the absence of classical orthostatic hypotension, the presence of transient initial orthostatic hypotension10 does not rule out a POTS diagnosis.5 The patient’s heart rate increase should be at least 30 bpm (or ≥ 40 bpm for those aged 12–19 years) in at least two separate measurements taken a minute apart (Box 2). The Canadian Cardiovascular Society statement5 stipulates a minimum supine heart rate of 60 bpm to avoid misdiagnosing POTS in individuals with naturally low resting heart rates that only reach normal levels upon standing.

It is important to note that normal physiological orthostatic tachycardia can fluctuate slightly daily, and diurnal variations exist, with greater orthostatic tachycardia typically occurring in the morning compared to later in the day.11 Therefore, if POTS is strongly suspected but the patient does not initially meet the orthostatic tachycardia criterion, a follow-up assessment at a later date, preferably in the morning, is advisable.

Epidemiology and Natural Progression of POTS

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is recognized as one of the most prevalent disorders of the autonomic nervous system, with prevalence estimates ranging from 0.1% to 1%.1,12,13 It predominantly affects adolescent girls and young adult women,4 leading to a higher prevalence in this demographic and lower rates in men and older populations. POTS is considered a heterogeneous syndrome encompassing various underlying causes that can manifest in similar clinical presentations. While orthostatic symptoms are essential for diagnosis, the range of other symptoms and clinical features can differ significantly among patients, and there’s symptom overlap with other clinically defined syndromes.8

Currently, there is limited research on the long-term natural history of POTS. Among children, orthostatic intolerance seems to improve with treatment over time, although a longer duration of symptoms before initiating therapy has been linked to less favorable long-term outcomes.14 Data regarding the natural history of POTS in adults is lacking; clinical experience suggests that while symptoms and function can improve with treatment, many patients do not experience complete and lasting remission.3,15

Differential Diagnosis: Conditions Mimicking POTS

Several conditions can be mistaken for POTS by both clinicians and patients if the focus narrows solely to symptomatic orthostatic intolerance or excessive orthostatic tachycardia. For instance, patients experiencing vasovagal syncope may have recurrent episodes of lightheadedness while upright, in addition to intermittent fainting spells. These individuals typically exhibit normal orthostatic vital signs, but some may also present with orthostatic sinus tachycardia.16

Patients with confirmed orthostatic hypotension, defined as a drop of 20 mm Hg or greater, may also experience orthostatic intolerance symptoms and orthostatic tachycardia. However, the presence of orthostatic hypotension excludes a diagnosis of POTS.6 Initial orthostatic hypotension is more frequently observed among adolescents and young adults, causing immediate lightheadedness upon standing, but symptoms typically resolve within 45 seconds of standing still.

Some individuals report symptoms of orthostatic intolerance without exhibiting orthostatic tachycardia or hypotension, and in these cases, a definitive cause may remain unidentified. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society categorizes these patients as having “postural symptoms without tachycardia.”5

It’s important to remember that not all cases of orthostatic tachycardia are indicative of POTS. Most POTS patients have a resting heart rate that is either normal or on the higher end of normal.17 If a patient presents with a consistently elevated heart rate, regardless of body position, they may be experiencing inappropriate sinus tachycardia. This condition is characterized by a consistent resting heart rate of at least 100 bpm or a 24-hour average heart rate exceeding 90 bpm. Patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia experience distressing symptoms without an apparent underlying cause.7 If the tachycardia stems from another identifiable condition known to cause sinus tachycardia, such as those listed in Box 3, the diagnosis becomes “postural tachycardia of other cause.”5

Box 3: Other Conditions That Can Explain Sinus Tachycardia Upon Standing 5

- Acute hypovolemia (due to dehydration or blood loss)

- Anemia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Endocrinopathy

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Carcinoid tumor

- Hyperthyroidism

- Pheochromocytoma

- Adverse medication effects

- Panic attacks and severe anxiety

- Prolonged or sustained bed rest

- Recreational drug use

Finally, it is crucial to differentiate between sinus tachycardia, characteristic of POTS, and other supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Clinicians should consider paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, particularly if the tachycardia is not consistently related to posture, has a sudden onset and offset (unlike the gradual increase in heart rate in POTS), or if it terminates with a Valsalva maneuver.

Comorbid Conditions Commonly Associated with POTS

Patients diagnosed with POTS often present with other coexisting symptoms and diagnoses. It remains unclear whether these define distinct pathophysiological subtypes of POTS. Headaches and sleep disturbances are almost universally reported. Exercise intolerance is common, with over 90% experiencing chronic fatigue, and at least half meeting the diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).18 A particularly debilitating symptom is “brain fog” or perceived cognitive impairment,19 which often intensifies in an upright position.20 Gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, bloating, and functional bowel symptoms are also frequent. Another common physical sign is peripheral acrocyanosis, characterized by bluish discoloration in the lower extremities when standing. Common comorbid conditions observed alongside POTS4,21 include hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, mast cell activation syndrome,22 migraine, and ME/CFS (Table 1).18

Table 1: Comorbid Conditions Associated with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome*

| Comorbid Condition | Common Clinical Features | Prevalence, % |

|---|---|---|

| Migraine Headaches | – Frequent, often throbbing and unilateral headaches – Possible prodrome | 40 |

| Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome & Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder | – Hyperextensible joints with frequent subluxation – Significant peri-joint pain | 25 |

| Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | – Profound fatigue with regular activities – Post-exertional malaise | 21 |

| Fibromyalgia | – Severe and diffuse myofascial pain | 20 |

| Autoimmune Disorders | – Often pre-existing diagnoses – Chronic dry eyes or mouth | 16 |

| Mast Cell Activation Disorder | – Strong allergic tendencies – Dermatographism – Frequent severe flushing | 9 |

| Celiac Disease | – Abdominal cramping and diarrhea – Gluten sensitivity | 3 |

Data adapted from Shaw et al.4 under Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

The reported frequencies of these clinical associations vary, and the quality of evidence supporting them is generally weak. Self-reported survey data4 indicates that approximately 40% of POTS patients experience migraines, 20%–30% meet criteria for hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or hypermobility spectrum disorder,23 and about 15% have a comorbid autoimmune disease. A review analyzing the rates of POTS and other forms of orthostatic intolerance in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome found that orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia occurred in 35%–50% of patients with hypermobility spectrum disorder.24 Some POTS patients exhibit symptoms suggestive of abnormal mast cell activation, reporting episodes of flushing, urticaria, dyspnea, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.25 Hypermobility spectrum disorder and mast cell activation disorder may coexist in some POTS patients.

Upon initial presentation, POTS is often misdiagnosed as an anxiety disorder. A large-scale survey of POTS patients revealed that 77% were initially told they had a psychiatric or psychological disorder before receiving a POTS diagnosis. This figure decreased to 37% after accurate diagnosis.4 These misdiagnoses likely occur because anxiety can be associated with tachycardia, palpitations, and lightheadedness, symptoms that overlap with POTS.

Pathophysiology: Understanding the Mechanisms of POTS

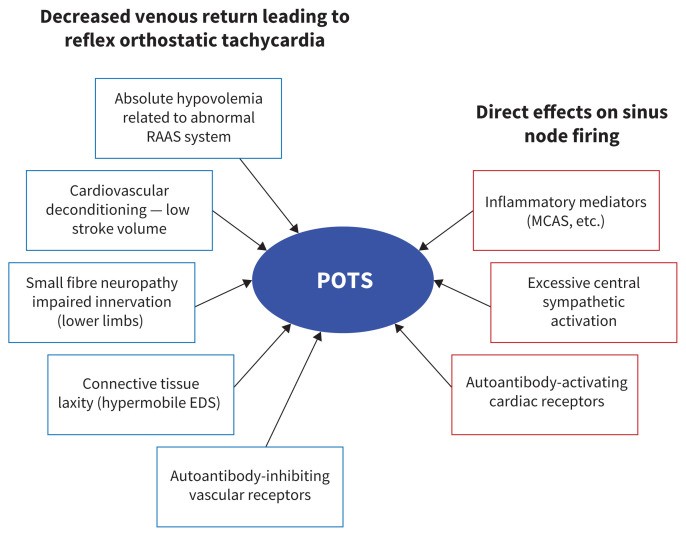

Figure 1 illustrates some of the proposed pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POTS. A majority of POTS patients exhibit low cardiac stroke volume,26 which may contribute to the sinus tachycardia. Subgroups of POTS patients are characterized by features such as increased sympathetic nervous system activity (hyperadrenergic POTS),17 partial peripheral sympathetic denervation leading to relative central hypovolemia (neuropathic POTS),27 and low blood volume (absolute hypovolemia),28 which may influence other hemodynamic findings. Hyperadrenergic symptoms can include tremors, anxiety, migraines, and angina-like chest pain.22 Some disruptions in the autonomic nervous system, especially the sympathetic nervous system, may be primary (central hyperadrenergic POTS) or secondary to another physiological abnormality, such as hypovolemia.

Figure 1: This diagram illustrates the proposed mechanisms behind Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, highlighting factors that reduce blood volume, impair venous return upon standing, and trigger reflex orthostatic tachycardia, as well as processes affecting sinus node response and chronotropic response during orthostasis. Conditions like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) are noted, along with the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS).

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome might also have an immunological basis. Many patients report a post-viral onset of symptoms,29–32 and 15%–20% of POTS patients have a history of autoimmune disorders like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, or Sjögren’s syndrome.4 Recently, numerous cases of POTS33 and other sinus tachycardias (e.g., inappropriate sinus tachycardia)34 have been reported following SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, comprehensive data on the prevalence of POTS among individuals with long-term COVID-19 complications (“long COVID syndrome”) is currently lacking. Autoantibodies targeting cardiovascular G protein–coupled membrane receptors are under intense research, but their precise role in POTS pathophysiology remains unclear.35

Clinical features of small fiber neuropathy have been traditionally used to diagnose partial autonomic neuropathy. Some POTS patients exhibit phosphorylated α-synuclein in skin biopsies,36 suggesting a neuropathic mechanism potentially shared with Parkinson’s disease and pure autonomic failure.

The increased prevalence of POTS within families suggests a genetic predisposition. While a specific mutation causing POTS in a single family has been identified,37 broader evidence supporting a monogenic cause for POTS is lacking.

Evaluating Patients for POTS: The Diagnostic Process

When POTS is suspected, the diagnostic process should include a detailed patient history, a physical examination with orthostatic vital signs measured at regular intervals after standing (and recording of associated symptoms), and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). A 24-hour Holter monitor can be used to detect inappropriate sinus tachycardia. This initial approach is generally sufficient for establishing a postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome diagnosis and starting treatment. While specialist expertise in POTS management may be limited in some regions, primary care physicians and pediatricians can effectively conduct the initial evaluation. If patients show poor or inadequate response to initial treatments, referral to a POTS specialist should be considered.

The patient’s medical history should focus on identifying potential underlying causes and associated disorders, possible triggers or precipitating events for POTS, symptom severity, factors that improve or worsen symptoms, the patient’s exercise capacity, and the impact of symptoms on their quality of life. Clinicians should inquire about symptoms suggestive of autonomic dysfunction, such as gastrointestinal or urinary issues, abnormal sweating, acrocyanosis, dry mouth, and unexplained fevers. Headaches, particularly migraines, are commonly reported, as is a combination of diarrhea and constipation. A significant portion of patients will describe symptoms related to altered gastric motility, including nausea and vomiting that can limit food and fluid intake. Some patients report nausea worsening in upright positions that improves with treatments targeting tachycardia. Bladder dysfunction symptoms like incontinence or urgency may also be present. Paresthesia and numbness in the limbs may indicate small fiber neuropathy, as autonomic nerves are small fibers. Heat and cold intolerance are frequently reported. Most patients complain of subjective cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”) and pervasive fatigue. A careful review of current medications is necessary, as some can exacerbate symptoms. It’s also important to assess the patient’s salt and water intake.

Heart rate and blood pressure measurements should be taken after the patient has been supine for 5–10 minutes to allow for fluid equilibration, and then at 1 minute, 3 minutes, 5 minutes, 8 minutes, and 10 minutes after standing.5 For diagnosing excessive orthostatic tachycardia (a key criterion for POTS), patients should exhibit a sustained heart rate increase of at least 30 bpm (for adults) or at least 40 bpm (for patients aged 12–19 years) on at least two standing measurements. Systolic blood pressure should not decrease by more than 20 mm Hg.

Given the significant diurnal variability of POTS, with greater upright heart rate and orthostatic tachycardia in the morning, morning assessments are likely to be more sensitive.11 While not always necessary, a head-up tilt table test (lasting at least 10 minutes), ideally with continuous beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring,38 can also be used to diagnose POTS. The tilt table test often elicits a slightly greater increase in heart rate compared to a stand test,39 enhancing its diagnostic sensitivity. Tilt table testing is frequently used in specialized referral centers as it can be combined with more advanced monitoring techniques.

In addition to orthostatic vital signs, the physical examination should include an assessment for joint hypermobility if Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is suspected or if the patient reports hyperflexibility.23,40 Cardiac auscultation may reveal signs suggestive of mitral valve prolapse. Patients with dependent acrocyanosis may exhibit a dusky red-blue discoloration of the feet and calves while standing, with skin that is cool to the touch.

Standard laboratory investigations5 should screen for secondary causes of orthostatic tachycardia, including hemoglobin, electrolytes, renal function, ferritin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and morning cortisol levels. Beyond ECG, routine cardiovascular or neurological investigations are not typically recommended initially. Further investigations should be guided by the initial evaluation findings (e.g., testing for Sjögren’s syndrome if suggestive symptoms are present or echocardiography if cardiovascular examination is abnormal). Testing for supine and upright fractionated plasma catecholamines and other hormones involved in blood pressure and blood volume regulation is sometimes conducted as part of a more advanced evaluation. Excessive increases in plasma norepinephrine upon standing may indicate increased sympathetic nervous system activity (“hyperadrenergic state”), which may be treatable with central sympatholytic medications.

POTS Treatment Strategies: Managing Symptoms and Improving Quality of Life

Currently, there is no cure for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Treatment goals focus on patient education, symptom management, improving physical conditioning, and enhancing overall quality of life. Treatment plans generally incorporate both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches. An initial treatment strategy is outlined in Box 4.

Box 4: Suggested Initial Treatment Approach for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

-

Non-pharmacological Treatments

- Initiate at the first visit:

- Increase water intake to 3 liters per day.

- Increase salt intake to 5 mL/day (2 teaspoons per day).

- Use waist-high compression garments.

- Initiate at the first visit:

-

Pharmacological Treatments

- Consider starting at the first visit if symptoms are severe:

- For very high standing heart rate: Propranolol 10–20 mg four times daily.

- If beta-blockers are contraindicated and standing heart rate is very high: Ivabradine 5 mg twice daily.

- If standing heart rate is not excessively high and blood pressure is low: Midodrine 5 mg orally every 4 hours, three times daily (8 am, noon, 4 pm).

- Consider starting at the first visit if symptoms are severe:

Note: tsp = teaspoon.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

It is recommended to discontinue any medications that might exacerbate orthostatic tachycardia. A small case–control intervention study from 2005 suggests that advising patients to consume 3 liters of water daily and maximize dietary salt intake can promote sodium retention and increase blood volume.28 A subsequent small 2021 case–control crossover study found that high sodium intake leads to expanded plasma volume and reduces upright norepinephrine levels and heart rate in POTS patients,41 although more long-term data is needed to confirm sustained benefits and assess potential long-term side effects. Compression garments for the lower body can help counteract gravity-induced fluid shifts upon standing and reduce orthostatic and standing tachycardia, as shown in a 2021 randomized crossover study on lower body compression during tilt table testing in POTS patients.42 Compression of both the abdomen and legs appears to be more effective than leg compression alone.42 A 2010 case–control intervention study suggests that regular, non-upright exercise focusing on aerobic reconditioning improves cardiovascular hemodynamics and reduces symptoms in POTS patients.26 However, experts caution that patients may initially feel worse and improvement may not be noticeable for up to a month.43

Pharmacological Options

Pharmacological treatments should be considered if patients present with severe symptoms initially or remain symptomatic after non-pharmacological strategies have been implemented. Currently, there are no large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of drug treatments for POTS, and no medications are specifically approved for POTS treatment in North America. Most drugs used for POTS aim to reduce upright sinus tachycardia or sympathetic tone, enhance vasoconstriction or venoconstriction, or increase blood volume (Table 2).

Table 2: Pharmacological Treatments for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

| Drug | Dosing | Quality of Evidence* | Adverse Effects | Other Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate Inhibitors | ||||

| Propranolol | 10–20 mg orally up to 4 times daily | Moderate | Hypotension, bradycardia, bronchospasm | Can worsen asthma |

| Ivabradine | 2.5–7.5 mg orally twice daily | Moderate | Visual disturbances, bradycardia | Expensive |

| Pyridostigmine | 30–60 mg orally up to 3 times daily | Low | Increased gastric motility and cramping | |

| Vasoconstrictors | ||||

| Midodrine | 2.5–15 mg orally 3 times daily | Moderate | Headache, scalp tingling, supine hypertension | Avoid within 4 hours of bedtime to prevent supine hypertension |

| Sympatholytic Drugs | ||||

| Methyldopa | 125–250 mg orally twice daily | Low | Hypotension, fatigue, brain fog | Start with a low dose |

| Clonidine | 0.1–0.2 mg orally 2–3 times daily or patch | Low | Hypotension, fatigue, brain fog | Start with a low dose; withdrawal can cause rebound tachycardia and hypertension |

| Blood Volume Expanders | ||||

| Fludrocortisone | 0.1 to 0.2 mg orally per day | Low | Hypokalemia, edema, headache | Monitor serum potassium levels |

| Desmopressin | 0.1 to 0.2 mg orally per day, as needed | Low | Hyponatremia, edema | Monitor serum sodium levels if used chronically |

Evidence quality assessed using GRADE methodology.44 Ratings: high, moderate, low, or very low, indicating confidence in effect estimates.

Propranolol, a beta-blocker, targets both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. A 2009 randomized crossover study demonstrated that low-dose oral propranolol improved tachycardia and reduced symptoms upon standing,45 and a small 2013 randomized, double-blind study showed improved exercise capacity46 in POTS patients. Propranolol’s short half-life necessitates dosing four times daily. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society recommends propranolol (10–20 mg, four times a day) with a “strong” recommendation.5 While most studies have focused on propranolol, bisoprolol may also be effective; comparative data is needed.

Ivabradine, an If channel blocker, reduces sinus node rate without beta-blocker effects. A 2021 single-center RCT found that ivabradine lowered heart rate and improved symptoms in some POTS patients.47 Insurance coverage for ivabradine can sometimes be challenging to obtain.

Pyridostigmine, a peripheral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, increases synaptic acetylcholine. A 2005 study showed that pyridostigmine (30–60 mg, three times daily) can acutely decrease upright heart rate in POTS patients;48 its action is thought to be through increasing vagal tone or enhancing sympathetic vasoconstriction. While generally well-tolerated, pyridostigmine can increase colonic motility and should be avoided in patients prone to diarrhea but may benefit those with constipation.49

Midodrine, a peripheral α1-adrenergic receptor agonist prodrug, enhances venous return, cardiac preload, and stroke volume. It may be most beneficial in POTS patients with accompanying low blood pressure.50 It’s typically prescribed at 2.5–10 mg every 4 hours (avoiding bedtime doses), but can also be used as needed for acute symptom relief.

Central sympatholytic drugs can be helpful for patients with increased sympathetic activity or hyperadrenergic features. Clonidine and methyldopa are antihypertensive medications that can reduce central sympathetic nerve traffic and norepinephrine release from peripheral sympathetic neurons. Both have narrow therapeutic ranges, requiring low starting doses.

Blood volume expanders are considered if non-pharmacological methods are insufficient or if low blood volume is confirmed by nuclear medicine blood volume assessments.51 Fludrocortisone (0.1–0.2 mg daily), a synthetic aldosterone, promotes renal sodium absorption and blood volume expansion; hypokalemia is a potential side effect. While a 2016 RCT suggests fludrocortisone reduces vasovagal syncope,52 evidence for its effectiveness in POTS is less robust, and controlled studies are lacking. Desmopressin, a synthetic vasopressin, promotes renal retention of free water and has been shown to acutely reduce orthostatic tachycardia in POTS patients,53 but requires careful monitoring for hyponatremia.

Procedural Treatments

Radiofrequency ablation of the sinus node has been explored as a POTS treatment.54,55 However, both the Heart Rhythm Society7 and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society5 currently advise against this and other procedural treatments for POTS due to lack of proven benefit and potential risks of serious harm.

Managing Comorbidities

A detailed discussion of managing the various comorbid conditions that frequently coexist with POTS (Table 1) is beyond the scope of this article. However, addressing these comorbidities is crucial for improving patient quality of life and overall function. This often necessitates referrals to appropriate specialists when management extends beyond general primary care.

Conclusion: Improving Recognition and Management of POTS

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is a chronic, multi-system disorder affecting the autonomic nervous system. Its defining characteristic is symptomatic, exaggerated sinus tachycardia in an upright position. POTS is more common in girls and women, typically starting around puberty and continuing into early adulthood. The condition can lead to significant functional disability, limiting the ability to work or attend school, and diminishing overall quality of life. Increased awareness among physicians and effective management strategies hold the potential to significantly improve the lives of individuals affected by POTS.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Satish Raj receives research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP142426), Dysautonomia International, and the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, supported by a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000445). He reports consulting fees from Lundbeck, Theravance Biopharma, and ArgenX BV, and payments and honoraria from Medscape, Spire Learning, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, and Autonomic Neurosciences. He also reports payment for expert testimony from Faris Law, paid participation on the data safety monitoring board for Arena Pharmaceuticals, and unpaid participation on boards with the American Autonomic Society and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Academy. Artur Fedorowski receives research support from Dysautonomia International. He reports consulting fees from ArgenX BV and payments and honoraria from Biotronick, Finapres Medical Systems, and Bristol Myers Squibb. He also reports consulting fees, honoraria, and participation on a data safety monitoring board with Medtronic. Robert Sheldon receives research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Dysautonomia International. He also reports 3 pending patents related to blood pressure monitoring and participation on a data safety monitoring board for a clinical trial on atrial fibrillation.

This article was commissioned and peer-reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafted the manuscript, critically revised it for important intellectual content, approved the final version for publication, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.