Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is a condition affecting the autonomic nervous system, most notably recognized by an abnormal increase in heart rate upon standing, often accompanied by lightheadedness and other debilitating symptoms. For individuals and healthcare professionals seeking clarity on this complex condition, understanding the Pots Diagnosis Criteria is crucial for accurate identification and effective management.

Core Diagnostic Criteria for POTS

The established POTS diagnosis criteria primarily hinge on a significant increase in heart rate when transitioning from a lying down (supine) to a standing position. Specifically, the current medical consensus defines POTS by the following heart rate response observed within the first 10 minutes of standing:

- Adults: An increase of 30 beats per minute (bpm) or more from baseline, or exceeding 120 bpm.

- Children and Adolescents: A more pronounced increase of 40 bpm or more is typically used as the threshold.

It’s important to note that these heart rate criteria must occur in the absence of orthostatic hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension, characterized by a drop in blood pressure upon standing, is a separate condition, though some POTS patients can also experience blood pressure fluctuations.

Image alt text: A person having their blood pressure measured with a sphygmomanometer, illustrating a common medical examination.

Diagnostic Tests for POTS

While the heart rate criteria form the cornerstone of diagnosis, various tests are employed to confirm POTS and rule out other conditions.

Tilt Table Test

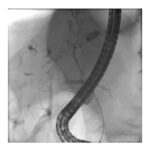

The Tilt Table Test is considered the gold standard for diagnosing POTS. This test involves strapping a patient to a table that is tilted to a near-upright position (typically 60-70 degrees) for a set period, usually ranging from 10 to 45 minutes. During the test, heart rate and blood pressure are continuously monitored. A positive Tilt Table Test for POTS will demonstrate the characteristic excessive heart rate increase without a significant drop in blood pressure.

Image alt text: A medical professional conducting a tilt table test on a patient, showcasing the equipment and procedure involved in POTS diagnosis.

Active Stand Test (Bedside Testing)

In situations where a Tilt Table Test is not readily available, an Active Stand Test can be performed at the bedside. This simpler test involves taking heart rate and blood pressure measurements while the patient is lying down, and then again at 2, 5, and 10-minute intervals after standing. The same heart rate criteria used for the Tilt Table Test apply to the Active Stand Test for diagnosing POTS.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that the Active Stand Test might not detect all cases of POTS. While useful as an initial diagnostic tool, caution should be exercised when excluding POTS based solely on a negative Active Stand Test, especially if the patient’s symptoms strongly suggest POTS.

Beyond Heart Rate: Comprehensive Autonomic Evaluation

Recognizing that POTS is a complex disorder affecting the autonomic nervous system, physicians may utilize more specialized tests to gain a deeper understanding of autonomic function in POTS patients. These tests go beyond just heart rate and blood pressure measurements and can help identify specific underlying mechanisms contributing to POTS.

Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test (QSART)

QSART, also known as Q-Sweat, evaluates the function of small nerve fibers that control sweating (sudomotor nerves). This test measures the volume of sweat produced in response to a stimulus, providing insights into the integrity of the autonomic nervous system’s sweat regulation. Approximately half of POTS patients exhibit small fiber neuropathy affecting their sudomotor nerves, making QSART a relevant diagnostic tool.

Thermoregulatory Sweat Test (TST)

Similar to QSART, the Thermoregulatory Sweat Test assesses sweating function, but over a larger body surface area. TST involves applying a powder to the skin that changes color in response to sweat. Patients are then exposed to increasing temperatures in a controlled environment, and the pattern of sweat production is observed and analyzed. TST can help identify regional abnormalities in sweat function, further indicating autonomic dysfunction.

Skin Biopsies for Small Fiber Neuropathy

To directly assess small fiber nerves, skin biopsies can be performed. These biopsies involve taking small samples of skin, typically from the leg, and examining them under a microscope to evaluate the density and health of small nerve fibers. Reduced small fiber nerve density can confirm the presence of small fiber neuropathy, a common comorbidity in POTS patients.

Gastric Motility Studies

Some POTS patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, bloating, and abdominal pain, suggesting autonomic dysfunction affecting the digestive system. Gastric motility studies evaluate how quickly and efficiently food moves through the stomach and digestive tract. Abnormalities in gastric motility can be indicative of autonomic neuropathy affecting the gut.

Signs and Symptoms Beyond Diagnostic Criteria

While the POTS diagnosis criteria are centered on heart rate, the syndrome manifests with a broader spectrum of symptoms that significantly impact patients’ quality of life. It’s crucial to consider these associated symptoms when evaluating for POTS.

Common signs and symptoms experienced by POTS patients include:

- Lightheadedness and Dizziness: Particularly upon standing.

- Fatigue: Persistent and often debilitating exhaustion.

- Headaches: Frequent and varying in severity.

- Heart Palpitations: Awareness of rapid or forceful heartbeats.

- Exercise Intolerance: Difficulty engaging in physical activity due to symptom exacerbation.

- Nausea: Feeling sick to the stomach.

- Cognitive Impairment (“Brain Fog”): Difficulty concentrating, memory problems.

- Tremulousness (Shaking): Involuntary trembling.

- Syncope (Fainting) or Pre-syncope (Near Fainting): Loss of consciousness or feeling faint.

- Coldness or Pain in Extremities: Poor circulation and nerve dysfunction.

- Chest Pain: Unrelated to cardiac ischemia in many cases.

- Shortness of Breath: Dyspnea, even without lung disease.

- Visual Disturbances: Blurred vision, tunnel vision.

- Sleep Disturbances: Insomnia, restless sleep.

It’s also worth noting the reddish-purple discoloration of the legs (acrocyanosis) some POTS patients develop upon standing, attributed to blood pooling in the lower extremities.

Image alt text: Discoloration of legs in a patient with acrocyanosis, demonstrating a visual symptom sometimes associated with POTS.

Differential Diagnosis: Ruling Out Other Conditions

When considering POTS diagnosis criteria, it’s essential to differentiate POTS from other conditions that may present with similar symptoms. These include:

- Orthostatic Hypotension: Characterized by a drop in blood pressure upon standing, unlike POTS which primarily involves heart rate increase without hypotension (though they can co-exist).

- Vasovagal Syncope: Fainting spells triggered by specific stimuli, typically with a slower heart rate response than POTS.

- Anxiety Disorders: While anxiety can mimic some POTS symptoms, POTS is a physiological disorder, not a psychiatric one. Importantly, POTS is not caused by anxiety, although anxiety can be a secondary symptom due to the challenges of living with a chronic illness.

- Hyperthyroidism: Can cause tachycardia and other symptoms overlapping with POTS.

- Cardiac Arrhythmias: Abnormal heart rhythms that need to be ruled out as a cause of tachycardia.

- Dehydration: Can exacerbate orthostatic symptoms and mimic POTS.

- Medication Side Effects: Certain medications can induce orthostatic intolerance.

A thorough medical history, physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic testing are crucial to accurately differentiate POTS from these and other conditions.

Conclusion: Accurate Diagnosis is Key to Management

Understanding POTS diagnosis criteria is fundamental for healthcare professionals in identifying and managing this often-misunderstood condition. While the heart rate response upon standing is the defining characteristic, a comprehensive evaluation, including symptom assessment, Tilt Table Test or Active Stand Test, and potentially further autonomic function testing, is necessary for accurate diagnosis. Recognizing the diverse symptoms and ruling out other conditions are also critical aspects of the diagnostic process. Early and accurate diagnosis allows for the implementation of appropriate management strategies to improve the quality of life for individuals living with POTS.

Sources:

- Grubb, B. P. (2008). Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation, 117(21), 2814-2817.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d.). Postural Tachycardia Syndrome Information Page.

- Raj, S. R. (2006). The postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal, 6(2), 84–99.

- Freeman, R., Wieling, W., Axelrod, F. B., Benditt, D. G., Benarroch, E., Biaggioni, I., … & Robertson, D. (2011). Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Autonomic Neuroscience, 161(1-2), 46-48.

- Singer, W., Sletten, D. M., Opfer-Gehrking, T. L., Brands, C. K., Fischer, P. R., & Low, P. A. (2012). Postural tachycardia in children and adolescents: what is abnormal?. The Journal of pediatrics, 160(2), 222-226.

- Masuki, S., Eisenach, J. H., Johnson, C. P., Dietz, N. M., Benrud-Larson, L. M., Carter, J. R., … & Joyner, M. J. (2007). Excessive heart rate response to orthostatic stress in postural tachycardia syndrome is not caused by anxiety. Journal of applied physiology, 102(2), 1134-1142.

- Khurana, R. K. (2006). Experimental induction of panic-like symptoms in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clinical autonomic research, 16, 371-377.

- Schondorf, R., & Low, P. A. (1993). Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia. Neurology, 43(1), 132-137.

- Stewart, J. M., Glover, J. L., & Medow, M. S. (2006). Increased plasma angiotensin II in postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is related to reduced blood flow and blood volume. Clinical science, 110(2), 255-263.

- Kanjwal, K., Karabin, B., Kanjwal, Y., & Grubb, B. P. (2011). Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome following Lyme disease. Cardiology journal, 18(1), 63-66.

- Kasmani, R., Elkambergy, H., & Okoli, K. (2009). Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome Associated With Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice, 17(5), 342-343.

- Gazit, Y., Nahir, A. M., Grahame, R., & Jacob, G. (2003). Dysautonomia in the joint hypermobility syndrome. The American journal of medicine, 115(1), 33-40.

- American Society of Hematology. (2009). Platelet Delta Granule and Serotonin Concentrations Are Decreased in Patients with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.

- Kanjwal, K., Karabin, B., Kanjwal, Y., & Grubb, B. P. (2010). Autonomic dysfunction presenting as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome in patients with multiple sclerosis. International journal of medical sciences, 7, 62–67.

- Kanjwal, K., Karabin, B., Kanjwal, Y., & Grubb, B. P. (2010). Autonomic dysfunction presenting as orthostatic intolerance in patients suffering from mitochondrial cytopathy. Clinical cardiology, 33(10), 626-629.

- Antiel, R. M., Caudill, J. S., Burkhardt, B. E., Brands, C. K., & Fischer, P. R. (2011). Iron insufficiency and hypovitaminosis D in adolescents with chronic fatigue and orthostatic intolerance. Southern medical journal, 104(8), 609-611.

- Nand, N., Mohan, R., Khosla, S. N., & Kumar, P. (1989). Autonomic function tests in cases of chronic severe anaemia. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 37(8), 508-510.

- Blitshteyn, S. (2010). Postural tachycardia syndrome after vaccination with Gardasil. European journal of neurology, 17(7), e24-e25.

- Prilipko, O., Kishore, A., & Cheshire, W. P. (2005). Orthostatic intolerance and syncope associated with Chiari type I malformation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 76(7), 1034-1036.

- Kizilbash, S. J., Ahrens, S. P., Bhatia, R., Killian, J. M., Kimmes, S. A., Knoebel, E. E., … & Fischer, P. R. (2013). Long-term outcomes of adolescent-onset postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Clinical Autonomic Research, 23(5), 277-278.

- Bagai, K., Wakwe, C. I., Malow, B., Black, B. K., Biaggioni, I., Paranjape, S. Y., … & Raj, S. R. (2013). Estimation of sleep disturbances using wrist actigraphy in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Autonomic neuroscience, 177(2), 260-265.

- Raj, S. (2013). POTS – A World Tour. Dysautonomia International Conference.

- Schofield, J., Blitshteyn, S., Shoenfeld, Y., & Hughes, G. R. (2014). Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders in antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome (APS). Lupus, 23(4), 398-405.