Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) frequently goes undiagnosed in primary care (PC) settings, with medical records noting the diagnosis in only 2% to 11% of cases.1, 2 Alarmingly, fewer than half, or even a smaller fraction, of these PTSD patients receive appropriate treatment.3, 4 To improve patient care, increased focus is needed on both identifying PTSD and ensuring effective treatment when diagnosed.

Effective mental health (MH) treatment for PTSD involves pharmacotherapy and/or specialized MH counseling, including structured cognitive behavioral therapy or psychotherapy.5–9 The American Psychiatric Association’s guidelines recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a primary pharmacological intervention for PTSD. SSRIs are effective in reducing PTSD symptoms, have manageable side effects, and can simultaneously address common comorbidities like depression, anxiety, and panic disorder.5, 10 While research comparing treatment modalities is ongoing, current guidelines suggest that due to the limited effectiveness of pharmacotherapy alone for PTSD, clinicians should also refer patients for psychotherapy.6, 7, 10, 11

Literature suggests that factors like the severity of psychological distress correlate with the recognition and treatment of mental illness.1, 4, 12 It is reasonable to assume this applies to PTSD in PC, where patients with more severe symptoms might be more likely to receive MH treatment.1, 4, 11, 12 Furthermore, PC physicians are more adept at recognizing depressive symptoms, sometimes misdiagnosing PTSD as depression.13 Consequently, comorbid depression alongside PTSD might increase the likelihood of MH treatment.13 Finally, patients disclosing trauma-related symptoms to healthcare providers also appears to improve their chances of receiving MH treatment.1, 6, 7, 12–14

To better understand the factors influencing PTSD treatment in PC patients, a cross-sectional study was conducted to assess PTSD diagnosis and MH treatment records. Given the therapeutic overlap between PTSD and depression management (particularly with SSRIs), it was hypothesized that some PTSD patients might receive MH treatment without a formal PTSD diagnosis. These patients might be misdiagnosed with other MH conditions, especially depression, leading to fortuitous PTSD treatment due to this therapeutic overlap. It was also hypothesized that PTSD symptom severity and disclosure of trauma-related symptoms would correlate with receiving PTSD treatment.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a secondary data analysis of a cross-sectional study conducted in primary care clinics of an urban academic medical center, focusing on participants meeting PTSD diagnostic criteria.2 The analysis had three main parts: (1) using validated measures to establish PTSD prevalence, symptom severity, and depressive symptoms; (2) reviewing electronic medical records (EMRs) for MH diagnoses, SSRI prescriptions, and MH professional visits in the preceding year; and (3) using logistic regression to analyze associations between MH treatment and hypothesized independent variables. Detailed methodology is available elsewhere; key aspects are summarized below.2 The Boston University Medical Center’s Institutional Review and HIPAA Privacy Review Boards approved the study, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Recruitment and Enrollment

From February 2003 to September 2004, trained research assistants screened adult patients in primary care waiting areas for study eligibility. Inclusion criteria included English speaking, age 18-65, and a scheduled primary care appointment. 607 of 753 eligible patients (81%) enrolled.2 This analysis focuses on 133 patients diagnosed with current (past 12-month) PTSD using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 2.1 PTSD Module.16, 17 All participants provided informed consent, received $10 compensation, and were offered safety referrals post-interview.

Assessments and Data

Interview assessments

Research assistants collected demographic data and administered validated questionnaires. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview assessed current PTSD, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) measured depressive symptoms.15–17 The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-C) quantified PTSD symptom severity.18, 19 Participants were also asked about disclosing trauma-related symptoms to medical professionals (primary care physicians, MH professionals, other physicians, nurses, or social workers).

Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Data

The academic medical center used a comprehensive EMR system, documenting outpatient encounters, inpatient summaries, diagnoses, and prescriptions. MH services within the center were also documented, although visit content was inaccessible. Trained medical students and residents, supervised by an internist, reviewed each participant’s EMR for 12 months prior to study entry. EMR review focused on MH diagnoses and treatments (SSRI prescriptions and/or ≥1 MH professional visit).20, 21 MH diagnoses included ICD-9 coded PTSD, depression, anxiety, and panic disorder from problem lists or clinician notes (excluding MH visits). Data on MH professional type or therapy type was unavailable, but MH professionals could enter diagnoses and prescribe SSRIs, both captured in the EMR.

Main Variables

The primary outcome was receipt of MH treatment in the prior 12 months, defined as either an SSRI prescription and/or ≥1 MH professional visit, treatments potentially effective for PTSD. Key independent variables were: EMR mental health diagnoses (PTSD, depression, anxiety, panic disorder); PTSD symptom severity (highest quartile of PCL-C scores); comorbid depression (PHQ-9 score ≥9); and disclosure of trauma-related symptoms (dichotomous variable).15, 18, 19 Covariates included age, sex, race (black vs. other), marital status, education, employment, and income. Insurance status was excluded due to near-universal coverage.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and bivariate analyses used t-tests for continuous and chi-square tests for categorical data. Logistic regression was used to determine factors associated with MH treatment, testing independent variables and potential confounders significant in bivariate analyses (p<0.10).

Results

Characteristics of Patients with PTSD

The 133 PTSD participants had a mean age of 41 (SD=11) (Table 1). 62% were female, 56% black. Almost half were never married, 30% had <12 years of education, and 62% were unemployed/disabled. 67% earned <$20,000 annually. 71% also had comorbid depression.

Table 1. Characteristics of Primary Care Patients with PTSD at an Urban Safety Net Hospital: Overall and Stratified by Receipt of PTSD Treatment

| Variable | Total(N=133)N (%) | Any PTSD Treatment*(n=66)N (col %) | No PTSD Treatment(n=67)N (col %) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Years, mean (SD) | 41 (11) | 42 (11) | 39 (11) | 0.2 |

| Female Gender | 82 (62%) | 41 (62%) | 41 (61%) | 0.9 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 75 (56%) | 30 (45%) | 45 (67%) | 0.03† |

| White | 24 (18%) | 17 (26%) | 7 (11%) | |

| Hispanic | 13 (10%) | 9 (14%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Other | 21 (16%) | 10 (15%) | 11 (16%) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/live w/partner | 24 (18%) | 8 (12%) | 16 (24%) | 2.0 |

| Separated/Divorced | 38 (29%) | 23 (35%) | 15 (22%) | |

| Widowed | 8 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Never married | 63 (47%) | 31 (47%) | 32 (48%) | |

| Education | ||||

| < 12 years | 40 (30%) | 18 (27%) | 22 (33%) | 0.8 |

| 12 years | 45 (34%) | 23 (35%) | 22 (33%) | |

| > 12 years | 48 (36%) | 25 (38%) | 23 (34%) | |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Full-time | 21 (16%) | 5 (8%) | 16 (24%) | 0.01 |

| Part-time | 22 (17%) | 8 (12%) | 14 (21%) | |

| Student | 7 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Unemployed | 83 (62%) | 50 (76%) | 33 (49%) | |

| Income | ||||

| < $20,000 | 85 (67%) | 45 (71%) | 40 (63%) | 0.3 |

| >= $20,000 | 41 (33%) | 18 (29%) | 23 (37%) | |

| Comorbid Depression‡ | 94 (71%) | 45 (68%) | 49 (73%) | 0.5 |

| Disclosure of Trauma-Associated Symptoms | 81 (61%) | 52 (79%) | 29 (44%) | <0.001 |

| More Severe PTSDSymptoms | 82 (62%) | 44 (67%) | 38 (57%) | 0.2 |

| EMR Documentation of Mental Illness | ||||

| Any Mental Illness§ | 83 (62%) | 58 (88%) | 25 (37%) | <0.001 |

| PTSD | 14 (11%) | 12 (18%) | 2 (3%) | 0.004 |

| Anxiety/Panic Attack | 30 (23%) | 22 (33%) | 8 (12%) | 0.003 |

| Depression∥ | 66 (50%) | 47 (71%) | 19 (28%) | <0.001 |

*Includes SSRI and/or visit with a mental health professional.

†P-value compares blacks vs. all other groups combined.

‡Depressive symptoms correlate with past 2 week major or other depression.

§Includes PTSD, anxiety, bipolar/manic disorder, panic disorder, major, and other, depression.

∥Major and other depression.

Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Documentation of Mental Illness

Table 1 details mental health diagnoses in EMRs. 88% of treated participants had at least one documented MH diagnosis, most commonly depression (71%). EMR documentation rates for PTSD (10% vs. 11%, p=0.9) and depression (44% vs. 52%, p=0.4) were similar between participants with PTSD alone (N=39) and those with PTSD and comorbid depression (N=94).

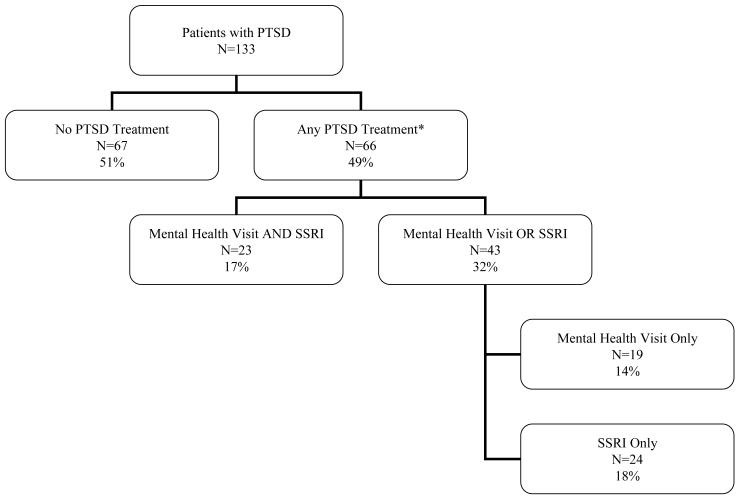

Receipt of MH Treatment

Nearly half of participants received MH treatment: 17% received both SSRIs and MH professional visits; 18% only SSRIs; and 14% only MH professional visits (mean visits 4.5, range 1-50) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Treatment Received by Patients with PTSD

*Mean number of visits with a mental health professional is 4.5; standard deviation 7.6. Range 1-50

Predictors of Receipt of MH Treatment

Bivariate analyses showed no significant differences in age or sex between treated and untreated groups. Fewer black participants received treatment, while more white and Hispanic participants did. A significantly higher proportion of treated patients were unemployed/disabled. PTSD symptom severity and comorbid depression were not significantly different between groups. However, a higher proportion of treated participants reported disclosing trauma-related symptoms. EMR documentation of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and/or panic disorder was also significantly higher in treated participants (Table 1).

Adjusted analyses indicated that the odds of MH treatment were 8.2 times higher (95% CI 3.1 – 21.5) for participants with any EMR mental health diagnosis, even without a PTSD diagnosis. Disclosure of trauma-related symptoms increased odds by 2.6 (95% CI 1.1 – 6.4). Unemployment/disability was also significant (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.1-6.7). Black race showed a trend towards lower treatment likelihood, though attenuated in adjusted analyses. PTSD symptom severity and comorbid depression were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2. Factors associated with receiving PTSD treatment*

| Factor | Odds Ratio† | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Medical Record Mental Health Diagnoses | 8.21 | 3.14.-21.52 |

| Disclosure of Trauma-Associated Symptoms | 2.61 | 1.06-6.43 |

| Unemployed/ On Disability vs. Employed/Student | 2.68 | 1.08-6.65 |

| Black Race vs. Others | 0.42 | 0.18-1.02 |

| Comorbid Depression | 0.52 | 0.18-1.49 |

| More Severe PTSD Symptoms | 1.32 | 0.50-3.51 |

*Adjusted Odds ratio via logistic regression modeling including factors statistically significant in bivariate analysis.

†As compared to patients who did not receive prior year PTSD treatment consisting of SSRI and/or visit with a mental health professional.

Discussion

In this urban PC patient sample with PTSD, PTSD diagnoses were rare in medical records. However, nearly 50% received MH treatment (SSRIs and/or MH professional visits). Besides PTSD diagnosis, any EMR MH diagnosis (depression, anxiety, panic disorder), disclosing trauma-related symptoms, and unemployment/disability were linked to receiving MH treatment.

Initial hypotheses that PTSD symptom severity and comorbid depression would positively correlate with treatment were not supported. This could be due to symptom improvement post-treatment or the study’s cross-sectional design.14 Meredith et al. cited time constraints and patient finances as major barriers to PTSD care, not diagnostic uncertainty.22 Kessler et al. showed that while initial consultations might miss mental illness, diagnoses and treatment often follow over time.14

Another hypothesis, that PTSD patients receive MH treatment despite lacking a PTSD diagnosis due to comorbid conditions or misdiagnosis, was supported. In our sample, 29% had PTSD alone and 71% comorbid PTSD and depression. EMR PTSD documentation was low (1 in 10), while depression documentation was 50%. Depression was more frequently documented in patients with both PTSD and depression, and often misdiagnosed in those with PTSD alone. This aligns with Samson et al., who found that depression and anxiety symptoms are more readily recognized and treated in PC patients with PTSD.13 Thus, therapeutic overlap in managing common mental illnesses leads to some PTSD treatment, even without proper diagnosis.2, 3, 5, 7, 8 However, undertreatment can lead to partially treated PTSD and related issues.23–25

While SSRIs are first-line for PTSD, depression, and anxiety, guidelines recommend specialized MH counseling (CBT or psychotherapy) as part of comprehensive PTSD treatment.5–10 For depression, antidepressant monotherapy is often sufficient.26, 27 CBT is more effective than SSRIs for PTSD, with 50% remission with CBT versus 30% with SSRIs.11 Guidelines recommend PC patients with PTSD be referred for psychological treatment.8, 9 In this study, most MH professional visits were likely not CBT or psychotherapy, as the mean number of visits (4.5) was less than typical CBT session lengths (9-12 sessions).28

Focused PTSD treatment is crucial, as incomplete treatment leads to suboptimal outcomes. Partially treated PTSD (Partial PTSD) still causes significant symptoms and increases suicide risk, despite being less severe than full PTSD.3, 23–25, 29–33 Untreated anxiety disorders, including PTSD, also increase healthcare utilization and costs.34 The US Preventive Services Task Force currently has no PTSD screening recommendations.35 Until guidelines are established and physicians are proficient in PTSD diagnosis, inquiring about trauma-related symptoms in patients with anxiety or depression, or in high-risk populations (e.g., veterans, those with substance dependence), could improve PTSD identification and referral.36 Prospective trials are needed to support routine inquiry.

Unemployment/disability was also linked to MH treatment, possibly because increased healthcare utilization leads to PTSD diagnosis.3, 4, 14 Unemployed/disabled PTSD patients may also be more available for treatment.14

Black participants were less likely to be diagnosed and treated for PTSD, even if attenuated in adjusted analysis. Cultural differences in trauma experience might partially explain this.37 Other studies suggest race can affect physician awareness of mental illness.38 Further research is needed to address this disparity.

Physician hesitancy to diagnose PTSD due to stigma or discrimination concerns might exist.39 However, studies show therapeutic benefits from accurate mental illness recognition.12 Ormel et al. found that recognizing mental illness, beyond treatment, positively impacts patient psychopathology and social functioning, due to acknowledgement, re-interpretation, and social support.12

Study limitations include the urban, safety-net hospital setting, potentially limiting generalizability, though similar settings exist in many US cities and mental illness studies in PC often show similar disability rates.40, 41 The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. For example, while trauma disclosure correlated with treatment, the temporal relationship is unclear.7 EMR data lacked treatment length and content details, adherence data, and information on treatment refusal or outside treatment. However, validated PTSD measures at study entry allowed for studying current mental illness and treatment received during documented illness. These data provide insights into factors affecting PTSD treatment in PC and highlight the need for research on patient and physician barriers to PTSD diagnosis and treatment.

Implications for Behavioral Health

In urban safety-net hospital PC patients with PTSD, half received MH treatment (SSRIs and/or MH professional visits), often for documented depression, anxiety, or panic disorder rather than PTSD. Treatment appears to be “fortuitous,” resulting from therapeutic overlap with other mental illnesses, particularly depression. Encouraging trauma-related symptom disclosure in PC could improve PTSD identification and treatment. Future research should focus on reducing patient and physician barriers to trauma disclosure and improving PTSD diagnosis and treatment in primary care to better serve those with this debilitating condition.

Acknowledgement

Andrew J. Meltzer, M.D. provided valuable comments on the manuscript.

Financial Support and Disclosure:

The work was supported by a Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar Award, RWJF #045452, from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey and by a career development award, K23 DA016665, from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (J.M.L.).

Footnotes

All Work Completed At: Clinical Addiction Research and Education (CARE) Unit, Section of General Internal Medicine, Boston Medical Center, 801 Massachusetts Avenue, 2nd Floor, Boston, MA 02118

Authors report no conflicts of interest.