Endovascular treatment has revolutionized the management of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) caused by large-vessel occlusion, often stemming from cardioembolic events. However, a significant portion, 15%–20%, of these strokes are linked to underlying tandem internal carotid artery occlusion or intracranial atherosclerotic disease. This is particularly prevalent in Asian populations. For these patients, maintaining vessel patency frequently necessitates concomitant stent placement during the acute stroke intervention.

A critical challenge following stent implantation is the elevated risk of thrombosis. Both bare metal and drug-eluting stents can exacerbate thrombogenicity, triggering platelet adhesion, activation, and thrombus formation. Dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) has long been a cornerstone in preventing thromboembolic complications in patients undergoing endovascular stent placement.

In emergency stroke scenarios where stent placement is crucial and patients are not already on DAPT, selecting the optimal antiplatelet strategy can be complex. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) inhibitors have proven safe and effective in various clinical settings. However, in AIS patients, especially those who have received intravenous fibrinolytic therapy, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is heightened, regardless of whether oral P2Y12 receptor inhibitors or IV GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used. The extended half-life of these medications becomes a potential disadvantage should intracerebral hemorrhage occur. Despite this risk, the potentially devastating consequences of vessel occlusion due to in-stent thrombosis often outweigh the hemorrhage concern.

Current neurointerventional antiplatelet strategies are largely adapted from interventional cardiology practices. Cardiology guidelines strongly recommend DAPT, often including a P2Y12 inhibitor like ticagrelor alongside aspirin, for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Cangrelor, a P2Y12 inhibitor, is also recognized for its utility in PCI, particularly when pretreatment with oral P2Y12 inhibitors is not feasible.

Despite its advantageous properties, cangrelor remains off-label for neuroendovascular interventions. Given the limited evidence base for cangrelor’s effectiveness in acute neuroendovascular stroke interventions, this study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of periprocedural intravenous cangrelor administration in AIS patients with intracranial or cervical artery occlusion requiring stent placement at a single center. This protocol for diagnosis and care seeks to address the critical need for effective and safe antiplatelet strategies in this challenging patient population.

Materials and Methods: Cangrelor Administration Protocol in Acute Ischemic Stroke

Patient Selection and Study Design

This retrospective study received approval from the Niguarda Cà Granda Hospital review board. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their next of kin. The institution’s standard consent for emergency endovascular procedures includes the use of antiplatelet drugs, including off-label use when necessary. The off-label use of cangrelor for neuroendovascular procedures was approved by our institution.

A prospectively maintained single-center database was searched to identify AIS patients who underwent endovascular procedures necessitating acute stent implantation and were treated with periprocedural cangrelor between January 2019 and April 2020. Inclusion criteria encompassed all patients requiring extracranial or intracranial stent placement in both anterior and posterior circulations.

Imaging and Procedural Protocol for Cervical Carotid and Intracranial Occlusion

The institutional protocol for AIS with tandem occlusions prioritizes a “retrograde fashion” approach, beginning with intracranial thrombectomy followed by stent placement, ideally under conscious sedation.

Diagnostic imaging included non-enhanced CT scans, multiphasic CTA, and CT perfusion to guide patient selection and treatment strategy. Neuroradiologists determined the thrombectomy technique (direct aspiration, stent-retriever, or combination) based on occlusion location. Balloon-guided catheters were reserved for intracranial or cervical ICA occlusions without concomitant intracranial occlusions.

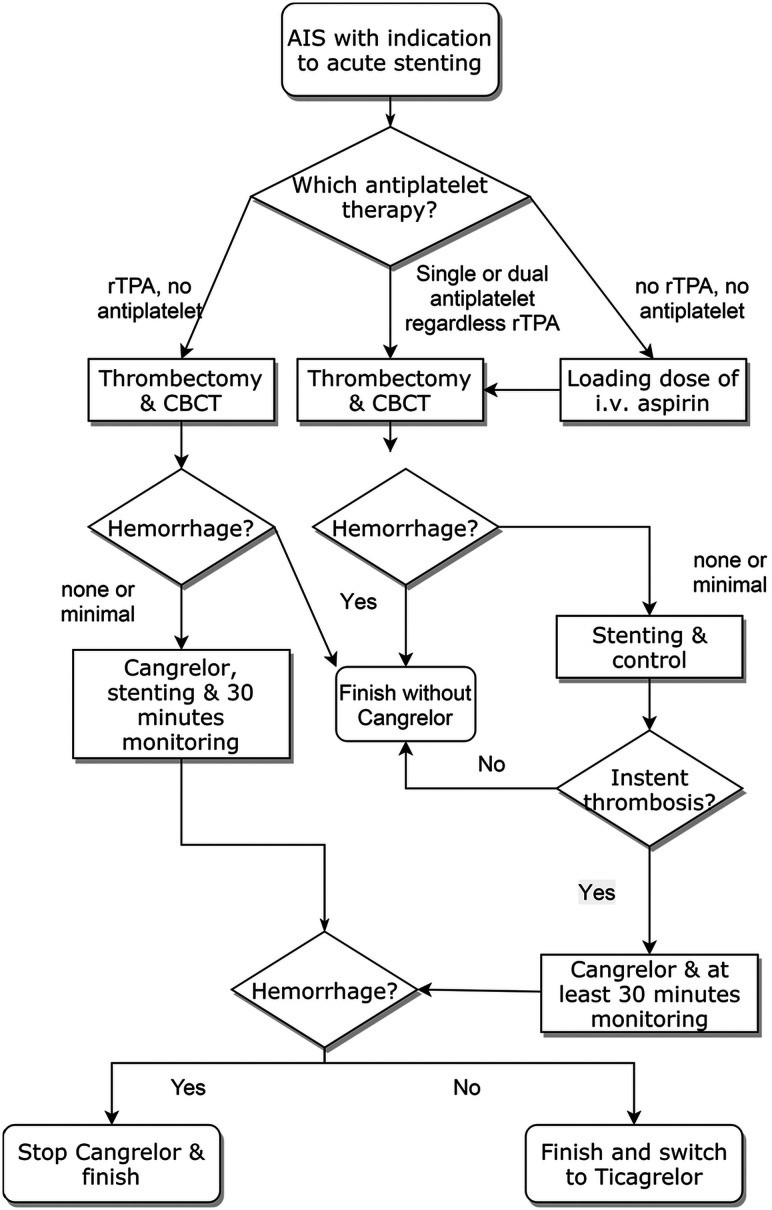

Stent placement was considered in the neurointerventional suite post-thrombectomy, provided no hemorrhagic complications occurred and successful recanalization (TICI 2b–3) was achieved, as outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Cangrelor and Stent Placement Decision Process for Acute Ischemic Stroke Management

Decision Process for Stent Placement and Cangrelor Use in Stroke Intervention.

Decision Process for Stent Placement and Cangrelor Use in Stroke Intervention.

Figure 1: Algorithm illustrating the decision-making process for stent placement and periprocedural cangrelor administration in acute ischemic stroke patients with cervical or intracranial artery occlusion. CBCT denotes cone-beam computed tomography to rule out immediate bleeding.

Intracranial bleeding, assessed via cone-beam CT in the angiosuite, was the sole exclusion criterion for cangrelor administration.

For patients not on pre-existing antiplatelet therapy and not receiving rtPA, intravenous aspirin (500 mg loading dose) was administered at the procedure’s outset when stent placement was deemed necessary. Post-stent placement, patency was monitored for 30 minutes in the angiosuite with angiograms every 10 minutes.

Cangrelor was initiated (30-μg/kg bolus followed by 4.0-μg/kg/min IV infusion) if intrastent thrombosis occurred. Infusion continued until transition to oral ticagrelor was feasible. A 180 mg loading dose of ticagrelor was given 30 minutes before discontinuing cangrelor. Antiaggregation effectiveness was not assessed via blood assay per institutional protocol. Post-procedure DAPT consisted of ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily) and aspirin (100 mg), with individualized adjustments as needed.

In patients initially treated with rtPA and without pre-existing antiplatelet therapy, cangrelor was administered immediately pre-stent placement, following the same protocol, after excluding hemorrhagic complications post-thrombectomy. Cangrelor was discontinued and ticagrelor withheld if hemorrhagic complications emerged during cangrelor infusion causing clinical deterioration.

Follow-up and Outcome Measures

Patients underwent continuous clinical monitoring in a Stroke Unit or Neurologic Intensive Care Unit for at least 24 hours post-procedure. A non-enhanced brain CT scan was scheduled at 24 hours, absent neurological deterioration signs. Cervical carotid artery stent patency was evaluated by Doppler sonography at 24 hours, while intracranial stent patency was assessed via intracranial CTA. CT perfusion scans were performed selectively if stent patency was questionable or signs of cerebral ischemia arose.

Primary outcomes included periprocedural and first-week post-treatment in-stent thrombosis and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in acutely stented patients.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used, with continuous variables as mean or median and categorical variables as absolute values and percentages. Statistical analyses were performed using R, Version 3.6.1.

Results: Cangrelor in Periprocedural Management of Stented Acute Ischemic Stroke

Between January 2019 and April 2020, 413 endovascular procedures for AIS were conducted at our center. Among these, 65 patients (15.7%) required stent implantation, with 38 (59%) receiving periprocedural IV cangrelor.

The mean age was 64 ± 13 years (range 26–85 years). Five patients received general anesthesia, and 33 were under conscious sedation. Ten patients (26.3%) had aspiration thrombectomy, 19 (50%) underwent combined aspiration and stent retriever techniques, and 6 (15.8%) used both aspiration and combined techniques. Cervical ICA stent placement was performed in 3 patients without intracranial occlusions (7.9%).

Six patients were treated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with one testing positive. Stroke onset time was unknown in 11 patients (28.9%). For others, mean onset-to-groin time was 305 ± 116.8 minutes (range 120–776 minutes). At treatment, 10 patients (26.3%) were on single or dual antiplatelet therapy for comorbidities, and one (2.6%) was on oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. Sixteen patients (42.1%) received IV thrombolysis, and 11 (28.9%) received intraprocedural aspirin before stent placement.

Tandem occlusions were present in 26 patients (68.4%) treated with cervical or intrapetrous carotid artery stent placement. Twenty-five Carotid Wallstents and one PRO-Kinetic Energy coronary stent were implanted. Intracranial stent implantation was required in 12 patients (31.6%) due to atherosclerotic disease or intracranial artery dissection. This group received 7 PRO-Kinetic Energy coronary stents, 4 Solitaire AB stents, and 1 Neuroform Atlas Stent System.

Successful recanalization (TICI 2b/3) was achieved in 97.4% of patients, except for one case (TICI 2a).

No intraprocedural stent occlusion occurred. Postprocedural stent occlusion within 24 hours occurred in 3 cases (7.9%). Two patients on clopidogrel did not switch to ticagrelor and experienced stent occlusion post-cangrelor. One underwent successful re-intervention with tirofiban and ticagrelor. The second, with MCA occlusion, did not undergo re-intervention, resulting in MCA territory infarction. The third patient with basilar artery stent occlusion experienced early occlusion due to clot progression despite ticagrelor administration.

One stent occlusion (2.6%) occurred within the first week. This patient, initially on ticagrelor and aspirin, was switched to ticlopidine and aspirin and re-occluded, requiring re-intervention and subsequent cangrelor and ticagrelor, achieving stent patency.

Vessel perforation with minimal subarachnoid hemorrhage occurred in 2 patients (5.2%) without clinical sequelae. Contrast media in the Sylvian fissure without clinical impact occurred in 4 patients.

Reperfusion ICH occurred in 4 patients (10.5%), none of whom received IV thrombolysis. One required surgical evacuation. Cangrelor cessation allowed safe surgery. In the remaining 3, ICH caused clinical deterioration but did not require surgery, and ICH progression was halted post-cangrelor discontinuation. Ticagrelor was withheld in all 4 ICH patients.

All hemorrhagic complications were in the ischemic territory. No new hemorrhagic complications occurred in the first postprocedural week.

Discussion: Cangrelor as a Therapeutic Option in Acute Stroke Stenting Protocols

This study represents a significant contribution to the limited literature on intraprocedural cangrelor use in AIS patients undergoing stent implantation for cervical and intracranial artery occlusion. Despite being a descriptive analysis without a control group, our findings suggest cangrelor’s potential effectiveness in preventing stent thrombosis without increasing hemorrhagic transformation risk, especially compared to other intraprocedural antiplatelet therapies. Cangrelor’s short half-life allows rapid cessation of antiplatelet action if hemorrhage occurs.

Few studies have explored cangrelor in emergency neuroendovascular procedures. Prior to this study, only 27 patients with AIS treated with cangrelor for stent implantation were documented. This study describes the largest series to date evaluating cangrelor in this context.

Before 2018, abciximab (ReoPro) was the primary antiplatelet drug used in our center for AIS stent placement. Its market withdrawal necessitated exploring alternatives. While tirofiban and eptifibatide (GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors) were considered, cangrelor emerged as a promising option due to its success in cardiology.

Cangrelor is a reversible, nonthienopyridine P2Y12 receptor inhibitor with rapid onset, short half-life, predictable pharmacokinetics, and metabolism to inactive compounds. It is FDA-approved for IV periprocedural use in PCI patients not pre-treated with P2Y12 or GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. The CHAMPION-PHOENIX trial demonstrated reduced adverse events with cangrelor versus clopidogrel in PCI.

Growing evidence supports cangrelor in STEMI PCI, prompting investigation in neurointerventions. Our results align with smaller case series using cangrelor in emergency stent placement for AIS and intracranial aneurysms, even at reduced doses. Studies using full-dose cangrelor for stent-assisted coiling or flow-diverter treatment of intracranial aneurysms also support its efficacy. Our low symptomatic ICH rate mirrors other cangrelor series post-stent placement.

Dosage heterogeneity exists in the literature. We used the standard PCI dose, consistent with most case series. One study used half-dose cangrelor without complications, but our full-dose decision was based on the unstable plaque similarity between AIS and PCI targets. Aneurysms carry a higher intrinsic hemorrhage risk than AIS. Future dose-ranging studies are needed to optimize efficacy and safety in AIS stenting protocols.

Cangrelor’s pharmacokinetic profile is ideal for acute interventions requiring rapid, effective, and short-acting antiplatelet therapy. Infusion can start intraprocedurally before stent placement without premedication, crucial in neuroendovascular procedures with hemorrhage risk. Rapid action allows for immediate stent placement and antithrombotic therapy after hemorrhage exclusion.

Cangrelor’s short half-life facilitates management of hemorrhagic complications. Antiplatelet activity resolves within an hour post-infusion, crucial for rapid hematoma evacuation without platelet transfusion. In contrast, GP IIb/IIIa or P2Y12 inhibitors may necessitate platelet transfusion, delaying treatment and increasing hemorrhage risk.

In our series, only one patient required surgical evacuation due to hematoma, managed safely due to cangrelor’s reversibility. Cangrelor may also be valuable as a bridging strategy, even at low doses, maintaining platelet inhibition during DAPT discontinuation for unplanned surgeries, with rapid return to baseline platelet function post-withdrawal.

Cangrelor is a potential first-line agent in chronic kidney disease patients, as renal function does not alter its pharmacokinetics, relevant given the common co-existence of renal dysfunction in AIS patients requiring high contrast media doses.

Ticagrelor (180 mg loading dose) is a safe and effective drug for maintaining antiplatelet activity post-cangrelor, providing continuous and predictable P2Y12 receptor blockade. Studies support ticagrelor switching from cangrelor. We avoided switching to ticagrelor in two clopidogrel-treated patients due to lack of data on combined use and potential hemorrhage risk increase. Cangrelor may competitively inhibit clopidogrel’s antiplatelet activity.

Early in-stent thrombosis in two of our cases occurred around 50 minutes post-cangrelor to aspirin/clopidogrel switch, coinciding with cangrelor’s duration of effect.

Poor blood pressure control in the four ICH patients may be a contributing factor, though direct correlation is unclear. Strict blood pressure management (systolic BP < 160 mmHg) is crucial post-carotid artery stenosis correction. Minor, self-limiting subarachnoid hemorrhage may allow continued cangrelor use with monitoring.

Study limitations include retrospective, single-center design, small sample size, short follow-up, lack of control group, and no platelet function testing. Underrepresentation of patients on oral anticoagulants limits generalizability.

Conclusions: Cangrelor Protocol Shows Promise for Acute Stroke Stenting

Despite limitations, this relatively large case series on periprocedural cangrelor in AIS patients with cervical or intracranial artery occlusion requiring stenting supports its potential as a valuable therapeutic option in emergency neuroendovascular interventions. Cangrelor offers rapid platelet function inhibition and quick resolution in hemorrhagic complications. While larger, randomized trials are needed to definitively establish its role, our findings and other preliminary data suggest cangrelor is a promising agent in the evolving protocols for diagnosis and care in acute ischemic stroke management involving stent placement.

Supplementary Material

20-00618.pdf

20-00618.pdf (23.8KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sirio Cocozza, MD, for his valuable assistance in the revision of the scientific English of this article.

ABBREVIATIONS:

AIS acute ischemic stroke

DAPT dual-antiplatelet therapy

GP glycoprotein

ICH intracerebral hemorrhage

PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: Federica Ferrari—RELATED: Other: scholarship from the Enrico ed Enrica Sovena Foundation, Rome, Italy.

References

[Include references from original article here, keeping the markdown format if provided]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

20-00618.pdf

20-00618.pdf (23.8KB, pdf)