Introduction

Low back pain stands as a prevalent global health concern, imposing a significant burden on society. It’s estimated that a substantial 70% to 85% of individuals in Western populations will experience low back pain at some point in their lives. Among the common culprits behind low back pain, Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ) pain emerges as a significant contributor, accounting for 15% to 30% of all cases. Notably, the SIJ often becomes the primary source of low back pain following lumbar or lumbosacral fusion surgery. Radiographic imaging reveals that SIJ degeneration occurs in a concerning 75% of patients within five years post-lumbar fusion surgery. Despite its considerable prevalence in chronic low back pain, SIJ dysfunction is frequently overlooked, underdiagnosed, and consequently, undertreated.

Think of the SIJ as a critical joint, much like a well-engineered component in a car’s suspension system. It’s a large diarthrodial joint connecting the sacrum to the ilium in the posterior pelvis. Just as a car’s suspension absorbs shocks from the road, the SIJ acts as a shock absorber, dissipating vertical forces from the spine and transmitting them to the hips and lower extremities. However, when the ligaments supporting the SIJ, especially the interosseous and posterior ligaments, become lax, the joint can become unstable. Similar to how excessive stress or misalignment can damage car parts, the primary mechanism of SIJ injury often involves a combination of axial loading and abrupt rotation. Repetitive microtrauma can also contribute to SIJ instability over time.

The causes of SIJ pain can be broadly categorized into traumatic and atraumatic origins. Traumatic causes often stem from sudden incidents like car accidents, falls, and injuries from lifting or twisting. Atraumatic causes encompass infections, cumulative injuries, multiple pregnancies, and inflammatory arthropathies. Factors that place stress on the SIJ, increasing the risk of dysfunction, include gait abnormalities, previous lumbar fusion, obesity, lumbar spinal stenosis, pregnancy, leg length discrepancies, and scoliosis. For any healthcare professional dealing with low back pain, understanding the reported symptoms and physical exam findings associated with SIJ dysfunction is essential. With advancements in durable pain relief solutions for SIJ pain and dysfunction, accurate diagnosis becomes even more critical to effectively treat this often-underestimated patient population.

History and Physical Exam

Differentiating SIJ disorders from other forms of low back pain requires a comprehensive diagnostic approach, combining a detailed patient history with a thorough physical examination. SIJ pain typically manifests as a unilateral or bilateral aching sensation below the L5 level, usually without numbness or paresthesia (tingling). Patients often describe low back pain that worsens after prolonged sitting, bending forward, and during transitions like getting out of bed or rising from a low chair or toilet. This pain can intensify with weight-bearing activities such as climbing stairs, bending, twisting, or even prolonged walking. Repetitive bending motions involved in activities like vacuuming, sweeping, mopping, gardening, and loading dishwashers can also exacerbate SIJ pain. Gait, or walking pattern, is frequently affected in individuals with SIJ pain. This dysfunction can involve reduced coordination of the gluteus maximus and the contralateral latissimus dorsi muscles, which are crucial for joint stability during walking – much like how balanced tire pressure and alignment are vital for smooth vehicle operation.

While no single physical exam maneuver is definitively diagnostic for SIJ dysfunction, a combination of specific findings and provocative tests plays a crucial role in identifying these disorders. Key physical exam provocative tests for SIJ dysfunction include the FABER test, compression test, distraction test, thigh thrust test, and Gaenslen test. A diagnosis of SIJ pain is typically considered when a patient exhibits positive results on at least three out of these five provocative maneuvers. Among these positive tests, either the thigh thrust test or the compression test should be positive to increase diagnostic confidence. Performing these provocative maneuvers provides an 85% pretest probability that an intra-articular joint injection, a key diagnostic procedure, will be successful in confirming SIJ pain. Supporting this, another study indicated that three or more positive SIJ pain provocation tests demonstrate a 91% sensitivity and 78% specificity in identifying SIJ dysfunction.

SIJ Provocative Tests

FABER Test (Patrick’s Test)

The FABER test, also known as Patrick’s test, is a key provocative maneuver for assessing SI joint dysfunction. To perform the FABER test, as shown in Figure 1, the patient lies supine on the examination table. The examiner positions the hip joint on the same side as the suspected SIJ pain into the FABER position. This involves flexing the ipsilateral knee to 90° and externally rotating the hip, placing the ipsilateral foot on the contralateral knee. Next, the examiner stabilizes the contralateral anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) by pressing it against the table while gently pushing the flexed knee down towards the table. A positive test is indicated if the patient reports pain in the SIJ area on the side where the knee is flexed. While some sources suggest the FABER test can also stress the contralateral SIJ, pain in the buttocks region during this test is generally suggestive of SIJ pain, whereas pain in the groin region may indicate hip pathology instead. When performed correctly, the FABER test is known to have one of the highest sensitivity rates among the five common provocative maneuvers for SIJ dysfunction. Interestingly, in today’s telemedicine landscape, patients can even perform a self-assessment of the FABER test. By sitting on a chair, crossing the ankle of the affected side over the opposite knee, and gently pushing down on the affected knee while leaning back in the chair, patients can provide valuable information to their healthcare provider remotely.

Figure 1.

Thigh Thrust Test (Posterior Shear Test)

The Thigh Thrust Test, also known as the Posterior Shear Test, is another crucial provocative maneuver for diagnosing SI joint dysfunction, illustrated in Figure 2. To conduct the Thigh Thrust Test, the patient lies supine while the examiner flexes the hip and knee of the tested side to approximately 90 degrees. The examiner then applies an anterior-to-posterior shearing force directly through the femur, targeting the SIJ. A positive test is indicated by the patient experiencing pain specifically at the ipsilateral SIJ. This test effectively stresses the sacroiliac joint by applying a direct posterior shear force, helping to identify SIJ dysfunction as the source of pain.

Figure 2.

Gaenslen Test

The Gaenslen Test is a provocative maneuver designed to assess SI joint pain by stressing the joint through hip hyperextension. As shown in Figure 3, to perform the Gaenslen Test, the patient lies supine near the edge of the examination table. The leg on the side to be tested is positioned hanging off the edge of the table, while the opposite hip and knee are flexed and brought towards the chest. The examiner then applies firm pressure to the flexed knee while simultaneously applying counter pressure to the knee of the hanging leg. This procedure is repeated on the opposite side to assess both SI joints. The Gaenslen test places stress on both SI joints bilaterally due to the opposing forces applied to each leg. A positive test is indicated if the patient experiences low back pain in the SIJ region during the test, suggesting SI joint dysfunction as the pain source.

Figure 3.

Gaenslen Test (Modified Technique)

A modified version of the Gaenslen Test exists to accommodate patients who may not be able to lie supine, as shown in Figure 4. In this Modified Gaenslen Test, the patient lies in a lateral decubitus position with the painful SIJ facing away from the table. The contralateral leg, the one closer to the table, is flexed towards the patient’s chest, similar to the positioning in the traditional Gaenslen test. The examiner stands behind the patient, who is positioned at the edge of the bed. To perform the test, the examiner stabilizes the pelvis with one hand by applying firm anterior pressure, while the other hand extends the patient’s lower extremity at the hip on the side of the painful SIJ. This modified technique is particularly useful for individuals who find lying supine uncomfortable or impossible. Like the traditional Gaenslen test, a positive result is indicated by the patient reporting pain in the SIJ region during the maneuver.

Figure 4.

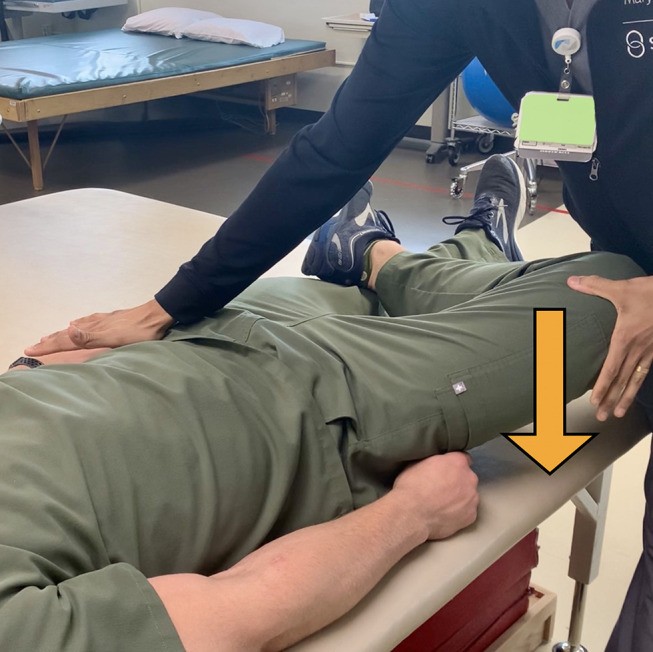

Compression Test

The Compression Test is another valuable provocative maneuver used to assess SI joint pain. To perform the Compression Test, as illustrated in Figure 5, the patient lies in a lateral decubitus position with the affected side facing upwards and turned away from the examiner. Standing behind the patient at the level of the pelvis, the examiner applies a firm downward pressure to the ipsilateral iliac crest and anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). The test is considered positive if the patient reports pain in the SIJ area on the ipsilateral side, indicating potential SI joint dysfunction. This test aims to compress the sacroiliac joint, provoking pain if the SI joint is the pain generator.

Figure 5.

Distraction Test

The Distraction Test is a provocative maneuver used to assess SI joint pain by applying a separating or distracting force to the joint. As shown in Figure 6, to perform the Distraction Test, the patient is positioned supine on the examination table. With the patient’s forearms crossed over their chest, the examiner applies a slow and steady outward pressure to both the left and right anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS), effectively spreading or distracting them apart. A positive test is indicated if the patient feels pain in the SIJ area during this distraction maneuver. This test stresses the anterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint, and pain provocation suggests SI joint dysfunction.

Figure 6.

Yeoman Test

The Yeoman Test is another provocative maneuver used to assess SI joint pain, focusing on stressing the anterior sacroiliac ligament. To perform the Yeoman Test, the patient lies in a prone position with the ipsilateral knee flexed at 90 degrees. The examiner then passively lifts the leg off the table, extending the hip. Pain reproduced specifically in the sacroiliac joint area suggests pathology of the anterior sacroiliac ligament, while anterior thigh paresthesia might indicate a femoral nerve stretch or tightness in the anterior thigh musculature. Studies have shown varied results for the Yeoman test’s diagnostic accuracy. One study reported a sensitivity of 64.1% and a specificity of 33.3%. However, another study by Weksler indicated positivity rates for the Yeoman test as high as 80%. These differing results suggest that while the Yeoman test can be a useful part of a physical examination, its results should be interpreted in conjunction with other findings and tests.

Diagnostic Imaging

While diagnostic imaging is a valuable tool in evaluating low back pain, it’s not definitively conclusive for diagnosing the specific source of pain, especially in SI joint dysfunction. However, imaging of the SIJ is crucial to rule out serious underlying conditions, often referred to as “red flags,” such as fractures, malignancies, or infections. Initial imaging typically involves lumbar and pelvis X-rays with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral views. These X-rays are helpful in excluding other causes of low back pain that can mimic SIJ pain, including hip osteoarthritis, lumbosacral spondylosis, and spondylolisthesis. The timing of when imaging is necessary varies based on the patient’s presentation and the presence of any “red flag” symptoms. Generally, for pain that has been present for less than six weeks, imaging is not immediately required. However, if pain persists for longer than six weeks, imaging should be considered. Additionally, if interventional therapy, such as injections, is planned, plain film X-rays should be obtained prior to the procedure. MRI of the lumbar spine may also be beneficial to rule out neural compression, particularly of the L5 nerve root.

The SIJ itself can be challenging to visualize clearly on standard radiographs, and definitive evidence of structural lesions within the joint may or may not be apparent on X-ray. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is frequently recommended for diagnosing sacroiliitis associated with HLA-B27 seronegative spondyloarthropathies, such as Psoriatic arthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis, and Reactive arthritis. MRI’s high sensitivity and ability to visualize bone marrow and SIJ edema, as shown in Figure 7, make it particularly useful in these cases. Bone marrow edema, highlighted by contrast enhancement on MRI, can be a significant indicator of sacroiliitis. In contrast, SIJ pain stemming from non-inflammatory arthropathy often presents with minimal findings on advanced imaging, but may reveal joint space narrowing, osteophytes (bone spurs), and sclerosis (bone hardening), as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

(A) Coronal view sacral T2 MRI with enhancement depicted by yellow arrows. (B and C) Axial and coronal view T1 MRI, respectively, showing post contrast enhancement depicted by yellow arrows. When these findings are seen concurrently in a patient, it is representative of bone marrow edema, which can be a sign of sacroiliitis.

Figure 8.

Diagnostic Injection

Accurately diagnosing SIJ pain can be challenging because there is no single pathognomonic clinical history, physical examination finding, or radiological evidence specifically for SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, symptoms of SIJ dysfunction can overlap with other common spinal conditions, such as lumbosacral facet syndrome, disc herniation, or proximal L5 nerve pathology. Given the lack of a definitive single test or imaging modality, intra-articular SIJ blocks, using local anesthetics with or without steroids, have become the diagnostic gold standard for confirming SIJ pain.

Historically, SIJ injections were performed without imaging guidance, relying solely on palpation techniques. However, studies have demonstrated the limitations of this approach. One study comparing blind SIJ injections to fluoroscopically guided injections found accurate needle placement in only 12% of blind injections. Image guidance significantly improves accuracy. Fluoroscopic guidance has been shown to be more accurate than ultrasound guidance (98.2% vs 87.3%) for SIJ injections, although both are considered reliable methods for accessing the SIJ. A primary limitation of ultrasound-guided SIJ injections is the inability to visualize an arthrogram, which is possible with fluoroscopy, to confirm intra-articular needle placement and rule out extra-articular injection. CT-guided injections have also been shown to facilitate intra-articular injections and effectively reduce SIJ pain symptoms. However, one study reported accurate needle placement in only 76% of CT-guided cases, suggesting it may not be superior to fluoroscopy in terms of accuracy. A more recent study even suggested improved efficacy with CT-guided injections compared to fluoroscopically guided injections in the SIJ, but CT-guidance has drawbacks including the lack of real-time contrast visualization, potential contrast extravasation, and increased radiation exposure.

Based on qualitative evidence, the diagnostic accuracy for SIJ blocks is categorized at Level II for dual diagnostic blocks showing at least 70% pain relief, and Level III for single diagnostic blocks with at least 75% pain relief. The recommended injection volume typically ranges from 1 to 2 mL. While some guidelines suggest single-injection diagnostic blocks for clinical studies, others advocate for double (confirmatory) diagnostic blocks to more accurately pinpoint the pain source. Double blocks involve using two different local anesthetics with varying durations of action. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) criteria for diagnosing SIJ dysfunction include pain in the SIJ region, pain reproducible with provocative maneuvers, and pain relief following local anesthetic injection into the SIJ or to the lateral branch nerves.

Diagnostic blocks should be assessed similarly to medial branch blocks used for facet joint pain. Pain relief should be evaluated immediately after the procedure. For the most rigorous diagnostic criteria, pain relief from an SIJ block should correlate with the duration of action of the anesthetic used. Pain logs can be helpful in tracking pain scores and accurately assessing the patient’s experience. Historically, a pain reduction of greater than 50% was used as the diagnostic cutoff for a positive SIJ block. However, more recently, a 75% pain reduction threshold has been recommended, particularly when considering dual diagnostic blocks prior to therapeutic SIJ treatments like radiofrequency ablation or fusion.

A posterior approach for SI joint injections is widely accepted. The patient is typically placed in a prone position. Fluoroscopic guidance is commonly used, with the fluoroscope positioned in a contralateral oblique orientation, approximately 20–35 degrees depending on individual pelvic anatomy, to align the anterior and posterior SIJ lines. The typical target for SIJ injection is the most inferior aspect of the joint, as shown in Figure 9. However, a superior and middle joint approach, illustrated in Figure 10, has also been described. A 22 or 25-gauge needle with a stylet is typically used for this approach. A small quantity of contrast medium, ranging from 0.2–0.5 mL when using fluoroscopic guidance, is essential to confirm proper intra-articular and extra-vascular needle placement, regardless of the SIJ entrance site. If contrast dye cannot be used due to allergy or kidney disease, biplanar fluoroscopy with contralateral oblique and lateral views can be used to verify appropriate needle tip placement within the joint.

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

Histological analysis of the sacroiliac joint has confirmed the presence of nerve fibers within the joint capsule and surrounding ligaments. The sacroiliac joint receives innervation from the ventral rami of L4 and L5, the superior gluteal nerve, and the dorsal rami of L5, S1, and S2. Sacral lateral branch nerve blocks have gained use, particularly for addressing pain originating from posterior sacroiliac structures, including the posterior joint and associated ligaments. However, there is additional ventral innervation of the SIJ that is typically inaccessible for blocks or denervation. Consequently, sacral lateral branch nerve blocks are primarily used to predict response to radiofrequency neurotomy (a nerve ablation procedure) and are not considered diagnostic for sacroiliac joint dysfunction itself. Current literature lacks evidence evaluating their use as a screening test for more definitive surgical procedures like sacroiliac fusion.

Differential Diagnosis

When patients present with posterior hip or low back pain below the L5 level or beltline, it’s crucial to consider various potential causes beyond sacroiliitis in the differential diagnosis. These include seronegative spondyloarthropathies, posterior femoro-acetabular pathology (hip joint issues), proximal hamstring tendinopathy, piriformis syndrome, sacral stress fractures, and referred pain from lumbar spinal pathology, such as lumbosacral facet-mediated pain and proximal L5 radiculopathy. While there are some overlapping symptoms among these conditions, recognizing specific findings can help differentiate them:

- Spinal or Spinal Nerve Pathology: Pain localized to the spine or radiating into the lower extremities, accompanied by a positive straight leg raise test, may indicate spinal or spinal nerve involvement.

- Femoro-acetabular Pathology: Concomitant anterior and posterior hip pain, with a FABER test provoking pain primarily in the groin area, may suggest hip joint pathology.

- Piriformis Syndrome: Tenderness to palpation over the piriformis muscle body, combined with a positive FADIR (Hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) test, may point towards piriformis syndrome.

- Pudendal Neuropathy: Perineal pain that worsens with palpation over the ischial spine may suggest pudendal nerve involvement.

- Hamstring Strain/Tendinopathy: Reproducible pain along the proximal hamstring muscle or tendon during active, passive, and resisted range of motion testing may indicate a hamstring issue.

- Lumbar Facet Arthropathy: Axial low back pain exacerbated by lumbar extension and a positive lumbar facet loading test may suggest lumbar facet joint pain.

- Sacrocoxalgia or Coccydynia: Pain localized over the inferior sacrum and coccygeal region may indicate pain originating from the sacrococcygeal joint or coccyx itself.

Understanding the relationships between these findings and their corresponding pathologies is vital for accurately identifying and appropriately addressing the patient’s source of low back and posterior hip pain. It’s not uncommon for SIJ pain to coexist with some of these other underlying conditions, so considering them in the differential diagnosis is essential for formulating a comprehensive and effective treatment plan.

Conclusion

Diagnosing SI joint pain is a comprehensive process that requires careful evaluation, much like diagnosing a complex automotive issue. Just as a mechanic relies on history, observation, and specific tests, diagnosing SIJ pain involves a detailed patient history, observation of gait patterns, and key physical exam maneuvers, including provocative tests. Thorough review of imaging studies is also crucial to rule out other potential causes of pain. Ultimately, diagnostic SIJ blocks serve as the confirmatory step in establishing the diagnosis. It’s equally important to consider and rule out other co-existing pathologies that might contribute to the patient’s symptoms. Once SIJ dysfunction is confirmed as the source of pain, various long-term treatment options become available, including SIJ ablation and SIJ fusion, whether posterior or lateral approaches are considered. Furthermore, it’s important to remember that spinal comorbidities often accompany SIJ dysfunction, and these should be regularly reassessed in patients with other pain conditions to ensure comprehensive and effective pain management.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

PB is a consultant for Abbott and PainTEQ. JMH is a consultant for Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Nevro. CB is a consultant for Nevro, Boston Scientific, Vertiflex, and PainTEQ. TD is a consultant for Abbott, Nalu, SPR, Saluda, PainTeq, Cornorloc, Vertiflex, Spinethera. Funded Research, Vertiflex (Boston Scientific), Abbott, Saluda, SPR. DS is a consultant for Abbott, Medtronic, Merit, Nevro, Painteq, SPR, and Vertos. NS is a consultant for Abbott and Nevro. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.