Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a prevalent chronic condition that necessitates ongoing management. This article serves as a guide for healthcare professionals, including primary care physicians, sleep specialists, surgeons, and dentists, offering a detailed approach to the diagnosis of OSA in adult patients, with a focus on Sleep Apnea Diagnosis Criteria.

Understanding Sleep Apnea and the Importance of Diagnosis

Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repeated episodes of upper airway collapse during sleep, leading to sleep disruption, oxygen desaturation (hypoxemia), carbon dioxide retention (hypercapnia), significant fluctuations in chest pressure, and heightened sympathetic nervous system activity. Clinically, OSA is identified by symptoms such as daytime sleepiness, loud snoring, observed pauses in breathing, or awakenings accompanied by gasping or choking. Crucially, sleep apnea diagnosis criteria include the presence of at least 5 obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep (apneas, hypopneas, or respiratory effort-related arousals) alongside these symptoms. Furthermore, even without noticeable symptoms, experiencing 15 or more obstructive respiratory events per hour is sufficient for an OSA diagnosis due to the elevated risk of serious health complications, notably cardiovascular disease.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has established practice parameters offering evidence-based recommendations for OSA diagnosis and management. This guideline consolidates these parameters and incorporates further literature review to provide a thorough strategy for evaluating, managing, and providing long-term care for adult OSA patients, with a central focus on the established sleep apnea diagnosis criteria.

Establishing Sleep Apnea Diagnosis: A Multi-faceted Approach

Diagnosis of OSA is essential before initiating any treatment. Determining the presence, absence, and severity of OSA is critical for identifying individuals at risk of complications, guiding appropriate treatment selection, and establishing a baseline to evaluate treatment effectiveness. The sleep apnea diagnosis criteria are grounded in clinical signs and symptoms obtained during a comprehensive sleep evaluation, encompassing a detailed sleep history, physical examination, and objective sleep testing.

History and Physical Examination: Identifying Risk Factors and Symptoms

The diagnostic process for OSA begins with a thorough sleep history. This typically occurs in routine health evaluations, assessments for OSA symptoms, or evaluations of individuals at high risk. High-risk groups include obese individuals, and those with conditions like congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, resistant hypertension, type 2 diabetes, stroke, nocturnal arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, professional drivers, and candidates for bariatric surgery.

Routine health evaluations should incorporate questions about snoring, daytime sleepiness, obesity, and retrognathia (receding jaw). Positive responses in this initial screening necessitate a more in-depth sleep history and physical examination.

A comprehensive sleep history for suspected OSA should evaluate for:

- Witnessed apneas: Breathing pauses observed by a bed partner.

- Snoring: Loud and disruptive snoring.

- Gasping or choking episodes: Nocturnal awakenings due to breathing difficulties.

- Excessive daytime sleepiness: Unexplained sleepiness, quantified using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

- Non-refreshing sleep: Feeling tired despite adequate sleep duration.

- Sleep fragmentation/maintenance insomnia: Difficulty staying asleep.

- Nocturia: Frequent nighttime urination.

- Morning headaches: Headaches upon waking.

- Decreased concentration and memory: Cognitive impairments.

Furthermore, the evaluation should consider secondary conditions potentially linked to OSA, such as hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, and motor vehicle accidents.

The physical examination complements the history by assessing respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological systems. Key indicators for OSA include:

- Obesity: Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2.

- Increased neck circumference: > 17 inches in men, > 16 inches in women.

- Modified Mallampati score of 3 or 4: Indicating oropharyngeal crowding.

- Retrognathia: Receding jaw.

- Upper airway narrowing: Including lateral peritonsillar narrowing, macroglossia (enlarged tongue), tonsillar hypertrophy, elongated uvula, high arched palate, and nasal abnormalities.

Following the history and physical exam, patients are categorized by OSA risk. High-risk individuals require expedited objective testing to confirm the diagnosis and determine severity, aligning with sleep apnea diagnosis criteria.

Objective Testing: Quantifying Sleep Apnea Severity

Objective testing is mandatory to establish the severity of OSA, as no clinical prediction model alone is sufficiently reliable. Accepted methods for objective testing are in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) and home sleep testing with portable monitors (PM).

Polysomnography (PSG)

PSG is the gold standard for diagnosing sleep-related breathing disorders. A comprehensive PSG for OSA diagnosis must record:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): To monitor sleep stages.

- Electrooculogram (EOG): To track eye movements.

- Chin electromyogram (EMG): To assess muscle activity.

- Airflow: To measure breathing.

- Oxygen saturation (SpO2): To monitor blood oxygen levels.

- Respiratory effort: To detect chest and abdominal movements.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) or heart rate.

- Body position.

- Leg EMG (anterior tibialis): To detect leg movements and movement arousals.

Attended PSG, with constant monitoring by a trained technologist, is crucial for ensuring data quality and patient safety. Scoring of sleep stages and respiratory events must adhere to the AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. The Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) or Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI), representing the frequency of obstructive events per hour of sleep, is calculated.

Full-night PSG is recommended, but split-night studies (diagnostic PSG followed by CPAP titration) are an acceptable alternative if the AHI reaches ≥ 40/hour within the first two hours of diagnostic recording, or potentially between 20-40/hr based on clinical judgment. In cases with strong OSA suspicion but inconclusive initial PSG, a second diagnostic PSG may be needed to solidify the diagnosis based on sleep apnea diagnosis criteria.

Sleep apnea diagnosis criteria based on PSG are met when the obstructive events (apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory effort-related arousals) are:

- Greater than 15 events/hour, OR

- Greater than 5 events/hour in patients presenting with sleep apnea associated symptoms such as:

- Unintentional sleep episodes during wakefulness

- Daytime sleepiness

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Fatigue

- Insomnia

- Waking up gasping or choking

- Bed partner reports of loud snoring or breathing interruptions

OSA severity is then categorized: mild (RDI ≥ 5 and < 15/hr), moderate (RDI ≥ 15 and < 30/hr), and severe (RDI ≥ 30/hr).

Portable Monitoring (PM)

Home sleep testing with PM can be used for OSA diagnosis as part of a comprehensive sleep evaluation, particularly in patients with a high pre-test probability of moderate to severe OSA and without significant comorbidities. PM devices should, at minimum, record airflow, respiratory effort, and blood oxygenation using sensors comparable to those used in PSG. Proper sensor application and data interpretation under the guidance of a board-certified sleep medicine physician are essential.

PM is generally not indicated for patients with significant comorbidities such as severe pulmonary disease, neuromuscular disease, or congestive heart failure, or when comorbid sleep disorders are suspected.

Sleep apnea diagnosis criteria using PM are the same as with PSG. However, it’s crucial to note that the RDI in PM is calculated as the number of events per total recording time, not total sleep time, potentially underestimating OSA severity compared to PSG-derived AHI. If PM results are technically inadequate or negative despite high clinical suspicion, in-laboratory PSG is recommended.

Other Sleep Procedures and Diagnostic Tools

The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) is not routinely used for initial OSA diagnosis but may be indicated if excessive sleepiness persists despite optimal OSA treatment, to evaluate for conditions like narcolepsy. Actigraphy alone is not sufficient for OSA diagnosis but can supplement PM by assessing rest-activity patterns during testing. Autotitrating Positive Airway Pressure (APAP) devices are not recommended for diagnostic purposes.

Patient Education: Empowering Individuals Through Understanding

Following objective testing, sleep specialists should discuss the results with patients, providing education on OSA, its nature, and treatment options. This includes explaining the pathophysiology, risk factors, natural history, and consequences of OSA. Treatment options should be discussed in the context of OSA severity, risk factors, co-existing conditions, and patient preferences. Education should also cover lifestyle modifications like weight loss, positional therapy, and avoiding alcohol, as well as the risks of drowsy driving.

Conclusion: Adhering to Sleep Apnea Diagnosis Criteria for Effective Management

Accurate diagnosis of OSA, based on established sleep apnea diagnosis criteria, is the cornerstone of effective management. This process involves a detailed clinical evaluation, including sleep history, physical examination, and objective sleep testing with PSG or PM when appropriate. By adhering to these guidelines, healthcare professionals can confidently diagnose OSA, determine its severity, and initiate tailored treatment plans to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Long-term management and follow-up are essential for this chronic condition.

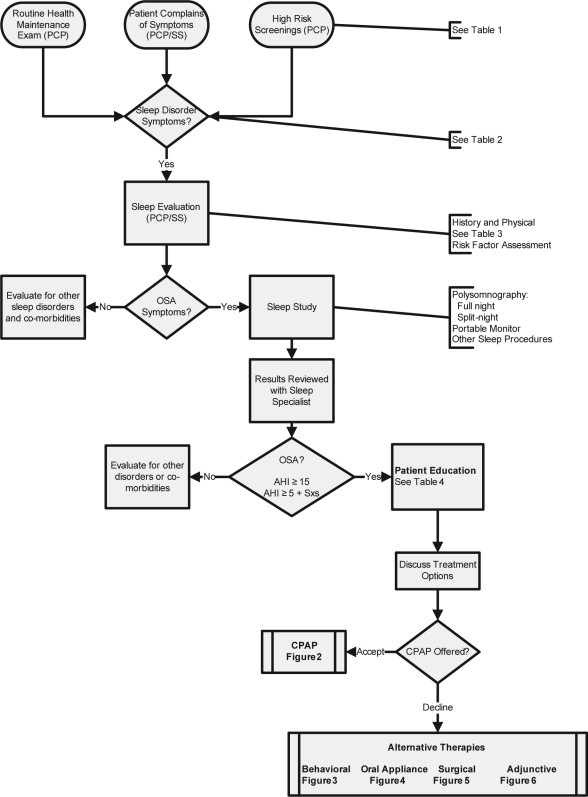

Figure 1.

Alt text: Flow chart illustrating the evaluation process for patients suspected of Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), detailing steps from primary care physician (PCP) referral to sleep specialist (SS) and diagnostic procedures.

Figure 2.

Alt text: Diagram outlining the approach to Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), including initiation, management strategies, and follow-up protocols.

Figure 3.

Alt text: Flowchart illustrating the process of behavioral treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), detailing initiation, management, and follow-up steps for lifestyle modifications.

Figure 4.

Alt text: Diagram describing the approach to Oral Appliance (OA) therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) patients, including initiation, management protocols, and necessary follow-up procedures.

Figure 5.

Alt text: Flow diagram illustrating the management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) through surgical therapy, outlining the steps involved in surgical treatment and patient care.

Figure 6.

Alt text: Diagram showing the approach to adjunctive therapies in the management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), detailing the integration of additional treatments to primary OSA therapies.

References:

[1] Epstein LJ; Kristo D; Strollo PJ; Friedman N; Malhotra A; Patil SP; Ramar K; Rogers R; Schwab RJ; Weaver EM; Weinstein MD. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(3):263–276.

[2] Fink, Arlene; Kosecoff, Jacqueline; Chassin, Mark; Brook, Robert H. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 1984;74(9):979–83.

[3] Collop NA; Anderson WM; Boehlecke B; Claman D; Goldberg R; Gottlieb DJ; Iber C; Kapur V; Lee-Chiong T; Meoli A; et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3(7):737–47.

[4] Kushida CA; Morgenthaler TI; Littner MR; Hirshkowitz M; Kryger MH; Haas ES; Wise MS; Oliveira CB; Aksamit TR; Bailey D; et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep 2006;29(2):240–3.

[5] Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14(6):540–5.

[6] American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the use of polysomnography and portable monitoring in the detection and diagnosis of sleep apnea in adults. Sleep 2005;28(12):1553–81.

[7] Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 1985;32(4):429–34.

[8] Chesson AL Jr, Anderson WM, Richards KC, et al. Practice parameters for the use of portable monitoring devices for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 1994;17(4):372–7.

[9] Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL Jr, Quan SF, for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

[10] American Academy of Sleep Medicine. AASM standards for accreditation of sleep disorders centers. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2008.

[11] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare benefit policy manual. Chapter 15 – Covered medical and other health services. Section 80.6 – Sleep disorder clinics. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2008.

[12] Flemons WW, Pillar G, Kryger MH, et al. Variability in diagnostic indices of sleep apnea. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2004;1(3):241–8.

[13] Littner MR, Kushida CA, Wise M, et al. Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and maintenance of wakefulness test. Sleep 2005;28(1):113–21.

[14] Sadeh A. The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: an update. Sleep Med Rev 2011;15(4):259–67.

[15] Morgenthaler TI, Aurora RN, Brown T, et al. Practice parameters for the use of autotitrating CPAP devices for titrating pressures and for long-term therapy of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: an update for 2007. Sleep 2008;31(3):341–8.

[16] Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet 1981;1(8235):862–5.

[17] Hoffstein V. Review of oral appliances for treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath 2007;11(1):1–22.

[18] Kushida CA, Littner MR, Hirshkowitz M, et al. Practice parameters for the use of continuous and bilevel positive airway pressure devices to treat adult patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Sleep 2006;29(3):375–80.

[19] Aurora RN, Zak RS, Maganti RK, et al. Best practice guideline for the titration of positive airway pressure for sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4(6):575–600.

[20] Piper AJ, Grunstein RR. Bilevel ventilatory support for obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 2007;62(12):1094–100.

[21] Loube DI, Gay PC, Strohl KP, et al. Indications for positive airway pressure treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: a consensus statement. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Chest 1999;115(3):863–6.

[22] Puhan MA, Lichtschlag J, Beule A, et al. Influence of body position on sleep apnea indices in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Respir Med 2006;100(11):1930–7.

[23] American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. The AADSM guideline for screening and referral of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Darien, IL: American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine, 2008.

[24] Aurora RN, Casey KR, Kristo DA, et al. Practice parameters for the surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Sleep 2010;33(5):575–99.

[25] National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1998.

[26] Dixon JB, Schachter LM, O’Brien PE, et al. Sleep apnea and weight loss surgery: cross-sectional and prospective study. Obes Res 2001;9(Suppl 11):125S–132S.

[27] Suratt PM, Dee P, Atkinson RL, Armstrong P, Wilhoit SC. The effect of very large weight loss on hip and neck circumference, and sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1993;147(4):826–32.

[28] Fletcher EC. Oxygen therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Med 1991;91(3):289–95.

[29] Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1990.