Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex, chronic autoimmune disease that can affect nearly any organ system in the body. Characterized by a loss of immune tolerance to self-antigens, SLE leads to the production of pathogenic autoantibodies and subsequent tissue damage through various immunological mechanisms. Understanding the multifaceted nature of SLE is crucial for healthcare professionals, especially when considering the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Differential Diagnosis. This article provides an in-depth review of SLE, emphasizing its diverse clinical presentations, diagnostic challenges, and the importance of a thorough differential diagnosis to ensure accurate patient care.

Etiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The precise cause of SLE remains elusive, but it is widely recognized as a multifactorial disease arising from a complex interplay of genetic, immunological, endocrine, and environmental influences.

Genetic Predisposition: Genetic factors play a significant role in SLE susceptibility. Studies involving twins and familial aggregation have demonstrated a strong genetic component. While no single gene is solely responsible, over 100 gene loci have been linked to polygenic SLE. These genes are primarily involved in immune system regulation, antigen presentation, and both innate and adaptive immune responses. Rare monogenic forms of SLE and SLE-like syndromes are associated with specific gene mutations, such as those affecting early complement components (C1q, C1r, C1s, C4, C2) and TREX1. The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) locus, containing HLA genes, represents the most commonly implicated genetic region.

Hormonal Influence: Sex hormones significantly impact SLE risk, with females being ten times more likely to develop the disease than males. Estrogens are thought to stimulate immune cells (T cells, B cells, macrophages) and cytokine production, promoting autoimmunity. Conversely, androgens are generally considered immunosuppressive. The higher prevalence in women and conditions like Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) points to a potential role of X-chromosome genes, although specific genes are yet to be identified.

Environmental Triggers: Various environmental factors can trigger SLE in genetically predisposed individuals. Drug-induced lupus is a well-documented phenomenon, with medications like procainamide and hydralazine being commonly implicated. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sun exposure is a known trigger for flares by inducing cell apoptosis and releasing self-antigens. Viral infections, particularly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), have also been linked to SLE development through molecular mimicry. Other potential environmental risk factors include smoking, silica exposure, vitamin D deficiency, and certain dietary components.

Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The epidemiology of SLE exhibits significant geographical and population-based variations. Prevalence rates range from approximately 72 to 74 per 100,000 individuals, with incidence rates around 5.6 per 100,000 person-years. Notably, African Americans experience the highest prevalence, followed by Asian and Hispanic populations, with Caucasians having the lowest rates. SLE tends to manifest earlier and exhibit more severe features in African Americans.

SLE predominantly affects women during their childbearing years, with a female-to-male ratio of 9:1. However, the risk in women decreases post-menopause, although it remains higher than in men. Interestingly, while less common in men, SLE in males often presents with more severe manifestations.

Age is a critical factor in SLE presentation. While most common in women of reproductive age, SLE can occur in children and the elderly. Pediatric SLE tends to be more aggressive than adult-onset SLE, frequently involving malar rashes, nephritis, and hematologic abnormalities. In contrast, elderly-onset SLE often has a more insidious onset with greater pulmonary involvement and fewer renal and neuropsychiatric complications.

Pathophysiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The pathogenesis of SLE is intricate and involves a breakdown of immune tolerance in genetically susceptible individuals exposed to environmental triggers. This leads to a chronic, self-directed immune response, causing inflammation and organ damage.

Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Both arms of the immune system contribute to SLE pathogenesis. The innate immune system is activated through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and cytosolic sensors by self-DNA and RNA released from damaged cells. This activation results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interferon-alpha (IFN-α) and IFN-β. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), released during NETosis, further amplify inflammation and serve as autoantigens.

The adaptive immune system plays a crucial role, with T and B lymphocytes driving autoantibody production. Antigen-presenting cells present self-antigens to T cells, leading to T cell activation and cytokine dysregulation. T cells, in turn, activate autoreactive B cells, promoting the production of pathogenic autoantibodies, a hallmark of SLE. These autoantibodies contribute to organ damage through immune complex deposition, complement activation, and direct cellular dysfunction.

Autoantibody-Mediated Damage: Autoantibodies in SLE target various self-antigens, including nuclear components like DNA, RNA, and proteins. Immune complexes formed by these autoantibodies deposit in tissues, triggering inflammation and tissue injury. Complement activation further enhances inflammation and cell lysis. Specific autoantibodies, such as anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith antibodies, are highly characteristic of SLE and can be used for diagnostic and prognostic purposes.

Histopathology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Histopathological findings in SLE are diverse, reflecting the complex immunologic mechanisms at play. The LE body or hematoxylin body, a globular mass of nuclear material, is a characteristic but not pathognomonic feature of SLE.

Skin Lesions: Skin biopsies of lupus lesions reveal immune complex deposition, vascular inflammation, and mononuclear cell infiltration. Acute lesions show fibrinoid necrosis at the dermo-epidermal junction, while chronic lesions may exhibit hyperkeratosis and scarring. Immunofluorescence commonly demonstrates deposits of IgG, IgA, IgM, and complement components along the dermal-epidermal junction.

Vasculitis: Vasculitis is a frequent finding in SLE, with varying patterns of vessel involvement. Immune complex deposition is the most common lesion, but necrotizing vasculitis can also occur. Thrombotic microangiopathy may be present, particularly in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Organ-Specific Pathology: Pathological findings vary depending on the organ involved. In the central nervous system, small vessel involvement with thrombotic lesions is typical. Cardiac pathology may include Libman-Sacks endocarditis, pericarditis, and myocarditis. Lupus nephritis, classified by the World Health Organization into six classes based on glomerular pathology, is a major determinant of prognosis. Lymph nodes often show follicular hyperplasia, while the spleen may exhibit “onionskin” lesions. Lung pathology in lupus pneumonitis includes interstitial pneumonitis and alveolar damage.

History and Physical Examination in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE presents with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from mild mucocutaneous involvement to severe, life-threatening multiorgan disease. A detailed history and physical examination are crucial for suspecting SLE and guiding the systemic lupus erythematosus differential diagnosis.

Constitutional Symptoms: Constitutional symptoms are common, affecting over 90% of patients. Fatigue, malaise, fever, anorexia, and weight loss are frequent presenting complaints. Fever in SLE can be due to disease flares or infections, necessitating careful evaluation.

Mucocutaneous Manifestations: Skin and mucous membrane involvement is highly characteristic of SLE, occurring in over 80% of patients. Lupus-specific skin lesions include acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE).

- ACLE: The classic malar rash (butterfly rash) is a hallmark of ACLE. It is an erythematous, photosensitive rash over the cheeks and nasal bridge, sparing the nasolabial folds. Generalized ACLE presents with a widespread maculopapular rash.

- SCLE: SCLE lesions are photosensitive, non-scarring rashes, often papulosquamous or annular in morphology. They are strongly associated with anti-Ro (SSA) antibodies.

- CCLE: Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is the most common CCLE subtype, characterized by disk-shaped, scarring lesions, often on the scalp and face. Oral and nasal ulcers are common in SLE, frequently painless initially. Photosensitivity is present in the majority of patients. Alopecia can be scarring (DLE-related) or non-scarring (lupus hair).

Non-specific cutaneous manifestations include vasculitis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, livedo reticularis, and others.

Musculoskeletal Manifestations: Musculoskeletal involvement is frequent, ranging from arthralgias to inflammatory arthritis. Lupus arthritis is typically non-erosive, symmetric polyarthritis affecting small joints. Jaccoud arthropathy, a deforming but reducible arthropathy, can mimic rheumatoid arthritis. Avascular necrosis is a potential complication.

Hematologic and Reticuloendothelial Manifestations: Anemia is common, often anemia of chronic disease, but hemolytic anemia and other types can occur. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are also frequent. Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are common findings.

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations: Neuropsychiatric SLE (NPSLE) is a significant concern. Headaches are the most common CNS manifestation. Seizures, cognitive dysfunction, psychosis, and various neuropathies can occur.

Renal Manifestations: Lupus nephritis is a major complication. Presentations range from mild proteinuria to rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. New-onset hypertension, hematuria, and edema should raise suspicion.

Pulmonary Manifestations: Pleuritis is the most frequent pulmonary manifestation. Pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary embolism can also occur.

Cardiovascular Manifestations: Pericarditis is the most common cardiac manifestation. Myocarditis, endocarditis (Libman-Sacks), and coronary artery disease are also seen.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations: Gastrointestinal involvement can affect any part of the tract, including esophageal dysmotility, mesenteric vasculitis, and lupus enteritis.

Pregnancy Complications: SLE in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of flares, fetal loss, pre-eclampsia, and neonatal lupus (due to anti-Ro/La antibodies).

Other Manifestations: Ocular involvement, including keratoconjunctivitis sicca and retinal vasculitis, is common. Ear involvement can lead to hearing loss.

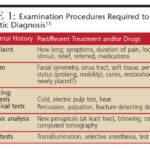

Evaluation and Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Diagnosing SLE is often challenging as there is no single pathognomonic test. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical features, laboratory findings, and exclusion of other conditions. The systemic lupus erythematosus differential diagnosis is a crucial part of the diagnostic process.

Autoantibody Testing: Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are highly sensitive for SLE, present in over 97% of cases. However, ANA is not specific and can be positive in other autoimmune diseases and even in healthy individuals. A negative ANA makes SLE less likely. Specific autoantibodies, such as anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith antibodies, are more specific for SLE. Anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies are seen in SLE and Sjogren’s syndrome. Antiphospholipid antibodies are associated with thrombosis and pregnancy complications.

Complement Levels: Low complement levels (C3, C4) suggest complement consumption and can correlate with disease activity.

Inflammatory Markers: Elevated ESR and CRP may be present, but CRP may not be as elevated in SLE as in other inflammatory conditions.

Complete Blood Count and Chemistry: CBC, liver function tests, renal function tests, and urinalysis are essential to assess organ involvement.

Imaging and Biopsy: Imaging studies (chest X-ray, CT scans, echocardiography, MRI) and biopsies (renal biopsy, skin biopsy) are used to evaluate organ involvement and confirm diagnosis.

Classification Criteria: Classification criteria, such as the ACR/EULAR criteria, are used primarily for research and can aid in diagnosis, but clinical judgment remains paramount. These criteria assign points to various clinical and immunological features; a score of 10 or more, with at least one clinical criterion, classifies a patient as having SLE.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Differential Diagnosis

The systemic lupus erythematosus differential diagnosis is broad due to the multisystemic nature of SLE. It includes a variety of autoimmune diseases, infections, and malignancies that can mimic SLE manifestations. A meticulous approach is required to differentiate SLE from these conditions.

1. Other Autoimmune Diseases:

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): RA can present with polyarthritis and extra-articular features, overlapping with SLE. While both can be ANA-positive, anti-CCP antibodies are specific for RA and absent in SLE. SLE-specific autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith) and hypocomplementemia are less common in RA.

- Drug-Induced Lupus: Distinguishing drug-induced lupus from idiopathic SLE can be challenging. Drug-induced lupus typically resolves upon drug discontinuation. Severe organ involvement is less common, although autoantibodies may persist.

- Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: Presents with fever, arthritis, rash, and systemic features, but lacks SLE-specific autoantibodies and malar rash.

- Behcet’s Disease: Characterized by oral and genital ulcers, uveitis, and arthritis, but lacks systemic and serological features of SLE.

- Sjogren’s Syndrome: Can overlap with SLE and share symptoms like fatigue, arthritis, and ANA positivity. However, Sjogren’s primarily affects exocrine glands, causing dryness. Anti-Ro/La antibodies are common in both.

- Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma): Can have overlapping features with SLE, particularly in early stages or mixed connective tissue disease. Scleroderma is characterized by skin thickening and Raynaud’s phenomenon, with distinct autoantibody profiles (anti-Scl-70, anti-centromere).

- Polymyositis/Dermatomyositis: Muscle weakness and skin rash can occur in both SLE and myositis. Myositis-specific antibodies (anti-Jo-1, etc.) help differentiate myositis.

2. Infections:

- Viral Infections: Parvovirus B19, Hepatitis B and C, CMV, EBV, and HIV can mimic SLE with fever, rash, arthritis, cytopenias, and ANA positivity. Viral serologies and absence of SLE-specific autoantibodies are crucial for differentiation.

- Infectious Endocarditis: Presents with fever, emboli, arthralgia, and cardiac murmur, potentially mimicking SLE cardiac manifestations. Blood cultures and lack of SLE autoantibodies are key differentiators.

- Lyme Disease: Can cause arthritis, fatigue, and neurological symptoms, but typically has a characteristic rash (erythema migrans) and positive Lyme serology.

3. Malignancies:

- Lymphomas: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can present with systemic symptoms, cytopenias, lymphadenopathy, and ANA positivity, mimicking SLE. Cancer screening and absence of SLE-specific autoantibodies are important.

4. Other Conditions:

- Fibromyalgia: Can co-exist with SLE and cause chronic pain and fatigue, but lacks objective inflammatory signs and SLE-specific autoantibodies.

- Sarcoidosis: Presents with fever, cough, rash, and uveitis, but characterized by non-caseating granulomas on biopsy and bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest radiography, rarely seen in SLE.

Treatment and Management of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

SLE management is aimed at preventing organ damage, controlling symptoms, and achieving remission. Treatment strategies are tailored to the specific organ systems involved and disease severity.

General Measures:

- Patient Education: Crucial for understanding the disease, medication adherence, and lifestyle modifications.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Stress reduction, good sleep hygiene, exercise, smoking cessation, and dietary recommendations (avoid alfalfa sprouts, vitamin D-rich diet).

- Photoprotection: Strict sun avoidance, protective clothing, and broad-spectrum sunscreen are essential.

Pharmacological Treatment:

- Hydroxychloroquine: A cornerstone of SLE therapy for cutaneous, musculoskeletal, and systemic manifestations. It also has anti-thrombotic and flare-preventing properties.

- Corticosteroids: Used for managing flares and moderate to severe organ involvement. Dosage and route depend on severity. Long-term use requires careful monitoring for side effects.

- Immunosuppressants: Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide are used to control inflammation and reduce corticosteroid dependence. Mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide are commonly used for lupus nephritis induction and maintenance.

- Biologics: Belimumab (anti-BAFF) and rituximab (anti-CD20) are approved biologics for SLE. Belimumab is used for active SLE, including lupus nephritis. Rituximab is used for refractory SLE, including hematologic and neuropsychiatric manifestations.

- NSAIDs: Used for mild musculoskeletal symptoms and serositis.

Organ-Specific Treatment: Treatment is tailored to the affected organ system, as detailed in the original article for cutaneous, musculoskeletal, hematological, cardiopulmonary, neuropsychiatric, renal, and pregnancy manifestations. Lupus nephritis requires aggressive immunosuppression based on the class of nephritis.

Prognosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Despite advancements in treatment, SLE remains a chronic disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Survival rates have improved, with 10-year survival around 85-90%. Cardiovascular disease, infections, and renal disease are leading causes of mortality. Early diagnosis, prompt treatment, and management of comorbidities are crucial for improving outcomes.

Poor Prognostic Factors: African American ethnicity, renal disease (especially diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis), male sex, young age at onset, older age at presentation, hypertension, low socioeconomic status, antiphospholipid syndrome, and high disease activity are associated with poorer prognosis.

Complications of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Complications in SLE can arise from the disease process itself or from treatment side effects.

Disease-Related Complications: Accelerated atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, end-stage renal disease, neuropsychiatric deficits, permanent skin damage, and pregnancy complications are major concerns.

Medication-Induced Complications: Corticosteroid-related complications (osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, cataract, glaucoma, infections), hydroxychloroquine maculopathy, and immunosuppressant-related side effects (cytopenias, infections, malignancy risk) require careful monitoring and management.

Deterrence and Patient Education in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Patient education is paramount in SLE management. Educating patients about disease manifestations, medication adherence, lifestyle modifications, and early recognition of flares can improve outcomes and quality of life. Support groups and mental health care are essential to address the psychological burden of chronic illness.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Optimal SLE care requires a multidisciplinary approach involving rheumatologists, primary care providers, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, dietitians, and specialists based on organ involvement (dermatologists, cardiologists, nephrologists, neurologists, etc.). Effective communication and collaboration among team members are essential to provide comprehensive, patient-centered care and improve outcomes in SLE.

Review Questions (Refer to original article)

References (Refer to original article)

Disclosure: (Refer to original article)