A testicular lump, also known as a testicular mass or swelling, refers to any abnormal growth or enlargement within the scrotum that originates from the testicles themselves. These lumps can be benign or malignant, and understanding their potential causes is crucial for timely diagnosis and appropriate management. Accurate differential diagnosis is essential to distinguish between various conditions presenting as a testicular lump, ensuring patients receive the correct treatment and avoid unnecessary anxiety or delays in care, especially when considering conditions like testicular cancer.

Clinical Evaluation of Testicular Lumps

A thorough clinical evaluation is the cornerstone of assessing a testicular lump. This process begins with gathering a detailed patient history, including:

- Onset and Duration: When did the lump first appear? Has it changed in size or characteristics over time?

- Pain: Is the lump painful? Is the pain constant or intermittent? Are there any factors that exacerbate or relieve the pain? Pain associated with a testicular lump can vary significantly depending on the underlying cause, ranging from painless in testicular cancer to severe in testicular torsion or epididymitis.

- Associated Symptoms: Are there any other symptoms, such as fever, urinary symptoms, groin pain, or a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum? Systemic symptoms like fever might suggest infection, while urinary symptoms could indicate related issues.

- Previous Episodes: Has the patient experienced similar lumps or scrotal issues in the past?

- Risk Factors: Are there any known risk factors for testicular conditions, such as cryptorchidism (undescended testicle), family history of testicular cancer, or history of sexually transmitted infections?

Physical examination is equally critical. The “6 S’s” provide a framework for visual inspection:

- Site: Where is the lump located within the scrotum? Is it within the testis itself or adjacent to it?

- Size: What is the approximate size of the lump? Has the size changed?

- Shape: What is the shape of the lump? Is it regular or irregular?

- Symmetry: Is the lump symmetrical or asymmetrical compared to the other testicle?

- Skin changes: Are there any changes to the overlying skin, such as redness, swelling, or skin thickening?

- Scars: Are there any scars present from previous surgeries or trauma?

Palpation, using the acronym CAMPFIRE, guides a systematic assessment of the lump’s characteristics:

- Consistency: What is the texture of the lump? Is it firm, soft, cystic, or solid? Testicular tumors are often firm or hard, while hydroceles are typically fluid-filled and softer.

- Attachment: Is the lump attached to the testis, epididymis, or surrounding structures? Or is it freely mobile?

- Mobility: Can the lump be moved within the scrotum?

- Pulsation: Is there a palpable pulse within the lump?

- Fluctuation: Does the lump feel fluid-filled and compressible? Fluctuation is characteristic of cysts and hydroceles.

- Irreducibility: If the lump is suspected to be a hernia, can it be reduced back into the abdomen?

- Regional lymph nodes: Are there any enlarged lymph nodes in the groin region? Lymphadenopathy can be associated with malignancy or infection.

- Edge: Are the borders of the lump well-defined or irregular?

- Tenderness: Is the lump tender to palpation? Significant tenderness is common in inflammatory conditions like epididymitis or orchitis, and testicular torsion.

- Temperature: Is the lump warmer than the surrounding tissue? Increased temperature can indicate inflammation or infection.

- Transillumination: Does light pass through the lump when a penlight is shone from behind? Transillumination is positive in fluid-filled sacs like hydroceles and epididymal cysts.

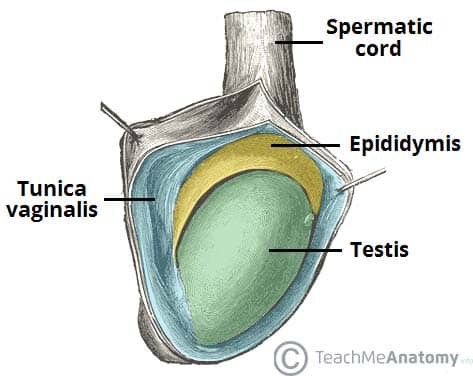

Crucially, during palpation, the examiner must carefully differentiate and separately assess the testis, epididymis, and vas deferens to pinpoint the origin and characteristics of the scrotal lump.

Diagnostic Investigations for Testicular Lumps

For most testicular lumps, especially those suspected to originate within the testicle, scrotal ultrasound is the primary and most valuable initial investigation. It provides detailed imaging of the scrotum and its contents, allowing for differentiation between solid and cystic masses, assessment of blood flow, and identification of anatomical abnormalities.

Further investigations, such as blood tests for tumor markers or advanced imaging like MRI or CT scans, may be necessary based on the ultrasound findings and clinical suspicion of specific conditions.

Investigating Suspected Testicular Cancer

Any testicular mass warrants prompt evaluation for testicular cancer, the most common malignancy in young men. It’s crucial to understand that biopsy of a testicular mass is contraindicated due to the risk of tumor cell seeding and spread. Diagnosis is based on clinical examination, ultrasound findings, and histopathological examination of the testis after orchiectomy (surgical removal of the testicle).

In cases of suspected testicular cancer, blood tests for testicular tumor markers are essential. These markers include:

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): Elevated in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

- Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG): Elevated in both seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): A non-specific marker but can be elevated in advanced testicular cancer and correlates with tumor burden.

These tumor markers aid in diagnosis, staging, and monitoring treatment response in testicular cancer.

Differential Diagnoses of Testicular Lumps

The differential diagnosis of a testicular lump is broad, encompassing both testicular and extra-testicular origins.

Figure 2 – A diagnostic flowchart illustrating the differential diagnoses for scrotal lumps, categorized by testicular and extra-testicular origins.Extra-testicular Causes of Scrotal Lumps

Extra-testicular lumps arise from structures surrounding the testicle, such as the epididymis, spermatic cord, or scrotal sac.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele is a collection of serous fluid within the tunica vaginalis, the membrane surrounding the testis. Hydroceles typically present as painless, soft, fluctuant swellings that transilluminate brilliantly. They can be unilateral or bilateral.

- Congenital hydroceles are common in newborns due to a patent processus vaginalis (a channel between the abdomen and scrotum). Many resolve spontaneously within the first year of life.

- Acquired hydroceles can occur at any age due to trauma, infection, inflammation, or testicular tumors. In men aged 20-40 years presenting with a hydrocele of unknown cause, or if the testis is not palpable, urgent ultrasound is recommended to rule out underlying pathology.

Large hydroceles can cause discomfort due to their size and weight. Treatment is usually reserved for symptomatic hydroceles and involves surgical drainage or aspiration.

Figure 3 – Scrotal ultrasound image revealing a large hydrocele, a fluid-filled sac surrounding the testicle, in a 55-year-old patient.Varicocele

A varicocele is characterized by the dilatation of the pampiniform plexus, a network of veins draining the testis. Varicoceles feel like a “bag of worms” upon palpation and are often more prominent when standing and may diminish or disappear when lying down. They can cause a dragging sensation or discomfort.

- Left-sided varicoceles are far more common due to the left testicular vein draining into the left renal vein at a 90-degree angle, predisposing it to higher pressure and reflux.

- Right-sided varicoceles or sudden onset varicoceles, especially in older men, warrant further investigation to rule out retroperitoneal masses obstructing venous drainage.

Varicoceles can be associated with infertility and testicular atrophy due to elevated scrotal temperature. Semen analysis and urology referral are indicated in men with varicoceles and fertility concerns. Asymptomatic varicoceles usually require no treatment. Symptomatic varicoceles or those associated with infertility may be treated with surgical ligation or percutaneous embolization.

Figure 4 – Ultrasound images demonstrating a varicocele: (A) B-mode image showing dilated veins of the pampiniform plexus, and (B) Doppler ultrasound confirming venous reflux within the varicocele.Epididymal Cyst (Spermatocele)

Epididymal cysts, also known as spermatoceles, are benign, fluid-filled cysts arising from the epididymis. They present as smooth, mobile, fluctuant nodules located superior and posterior to the testis. They transilluminate and are often multiple.

Epididymal cysts are common, particularly in middle-aged men. They are typically asymptomatic, benign, and require no treatment. Large or painful cysts may be surgically excised, although this is generally avoided in younger men due to potential fertility risks.

Epididymitis

Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis, frequently caused by bacterial infection. It presents with acute onset of unilateral scrotal pain, often accompanied by swelling, redness, and warmth of the scrotum. Systemic symptoms like fever may be present. On examination, the epididymis is exquisitely tender. Prehn’s sign (pain relief with scrotal elevation) may be present but is not a reliable diagnostic indicator.

In sexually active young men, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) like Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are common causes. In older men, urinary tract pathogens like Escherichia coli are more frequent. Treatment involves antibiotics and pain management.

Inguinal Hernia

An inguinal hernia occurs when abdominal contents protrude through the inguinal canal. Indirect inguinal hernias can extend into the scrotum, presenting as a scrotal lump. Hernias are often reducible, meaning they can be pushed back into the abdomen, and may become more prominent with coughing or straining. Crucially, on examination, you cannot “get above” an inguinal hernia in the scrotum, meaning the superior extent of the mass cannot be palpated within the scrotum itself.

Incarcerated or strangulated hernias are surgical emergencies requiring prompt intervention. All inguinal hernias should be evaluated for these complications.

Testicular Causes of Scrotal Lumps

Testicular lumps originate within the testis itself.

Testicular Tumors (Testicular Cancer)

While most scrotal lumps are benign, it is paramount to consider testicular cancer in the differential diagnosis of any testicular mass. Testicular tumors classically present as painless, firm, irregular masses within the testis. However, up to 5% of patients may experience testicular pain, potentially delaying diagnosis. Testicular tumors do not transilluminate.

Testicular cancer is most common in men aged 20-40 years. Any suspected testicular tumor requires urgent scrotal ultrasound and tumor marker assessment. Radical inguinal orchiectomy is the primary treatment for most testicular cancers. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy may be indicated based on tumor stage and histology. Prognosis for testicular cancer is generally excellent, with high survival rates when diagnosed and treated early.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency involving the twisting of the spermatic cord, compromising blood supply to the testis and causing ischemia. It presents with sudden, severe, unilateral scrotal pain, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

Testicular torsion is most common in adolescent boys and young men. Examination typically reveals a tender, swollen, and elevated testis. The cremasteric reflex (elevation of the testis in response to stroking the inner thigh) is usually absent. Scrotal Doppler ultrasound showing absent or reduced blood flow confirms the diagnosis.

Testicular torsion requires immediate surgical exploration and detorsion to salvage the testis. Time is critical, as testicular viability significantly decreases after 6 hours of torsion.

Figure 5 – Doppler ultrasound of the scrotum demonstrating a lack of blood flow to the testicle, indicative of testicular torsion.Benign Testicular Lesions

Rare benign testicular tumors include Leydig cell tumors, Sertoli cell tumors, lipomas, and fibromas. These are uncommon and usually diagnosed after orchiectomy performed for suspected malignancy.

Orchitis

Orchitis is inflammation of the testis, most commonly caused by viral infections, particularly mumps. Isolated orchitis is rare; it often occurs in conjunction with epididymitis (epididymo-orchitis). Mumps orchitis typically follows parotitis (swelling of the salivary glands). Symptoms include testicular pain and swelling. Treatment is supportive, with rest and analgesia. Rarely, testicular abscess formation may occur, requiring drainage or orchiectomy.

Key Considerations for Testicular Lump Differential Diagnosis

- A testicular lump necessitates a thorough clinical evaluation and prompt investigation.

- Scrotal ultrasound is the primary imaging modality for evaluating testicular lumps.

- Differential diagnosis includes both extra-testicular and testicular causes.

- Testicular cancer must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of a testicular mass, especially in young men.

- Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency requiring immediate intervention.

- Transillumination is helpful in differentiating fluid-filled cysts (hydroceles, epididymal cysts) from solid masses.

- Clinical history, physical examination, and investigations are crucial for accurate differential diagnosis and appropriate management of testicular lumps.

Flowchart for the Assessment of Scrotal Swelling – A visual guide to the diagnostic process for evaluating scrotal swellings, aiding clinicians in systematic assessment and management.