Introduction:

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition melanoma staging system, updated in 2018, represents a significant evolution from the 7th edition implemented in 2010. This article provides a crucial overview for dermatology professionals, especially those in urgent care settings, focusing on the impactful changes and their clinical implications. Understanding these updates, potentially accessible through resources like a symptom-based diagnosis e-book from 2017 reflecting earlier guidelines and highlighting the need for updated knowledge, is vital for accurate patient assessment and optimal management strategies in melanoma.

Areas Covered:

This article delves into the critical modifications introduced in the 8th edition AJCC staging system compared to the 7th. Based on extensive analyses of a large international melanoma database, we explore how these changes refine staging accuracy and prognostic prediction. We will also discuss the practical implications of these revisions for melanoma treatment protocols, ensuring dermatology practitioners in urgent care and beyond are equipped with the latest understanding.

Expert commentary:

For effective melanoma management, a robust and current cancer staging system is paramount. It provides the framework for precise risk stratification, which is indispensable for guiding patient care decisions. The 8th edition AJCC staging system stands as the current gold standard for melanoma staging and classification at initial diagnosis. In the context of urgent care dermatology, where rapid and informed decisions are critical, familiarity with these updated guidelines – potentially contrasted with resources like a 2017 symptom-based diagnosis e-book reflecting previous standards – is essential for delivering timely and appropriate care.

Keywords: Melanoma, TNM, staging, eighth edition, American Joint Committee on Cancer, AJCC, prognosis, Urgent Care Dermatology Symptom-based Diagnosis E-book2017

1. Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma incidence continues its upward trend in the United States, increasing by roughly 3% annually in recent decades [1]. While early-stage (I and II) melanoma patients generally have a positive prognosis, stage III melanoma presents a more varied outlook, and stage IV melanoma has historically been associated with poor survival rates. However, significant therapeutic advancements, including targeted molecular therapies and immunotherapies, have dramatically improved survival outcomes for patients with advanced and metastatic melanoma [2–5], and more recently, in the adjuvant setting [6,7]. A comprehensive grasp of melanoma prognostic factors and staging is fundamental for initial patient evaluation, treatment planning, surveillance strategies, and the design and interpretation of clinical trials. For dermatology professionals in urgent care settings, this knowledge is crucial for prompt and effective initial assessments, potentially utilizing symptom-based diagnostic approaches informed by resources like dermatology e-books, while staying updated with the latest staging criteria.

Reflecting advancements in our understanding of melanoma biology, the staging system has undergone several revisions. The 7th edition AJCC staging system for cutaneous melanoma was adopted in 2010 [8,9], and the 8th edition was implemented across the United States on January 1, 2018 [10,11]. Based on extensive analyses of a large international melanoma database, the Melanoma Expert Panel introduced key modifications in the 8th edition to enhance staging accuracy, prognostic prediction, risk stratification, and patient selection for clinical trials [10–12]. Detailed information on the database composition is available in the supplementary materials of reference 11. For dermatologists, especially those relying on symptom-based diagnosis in urgent care scenarios, understanding these shifts from previous editions, potentially outlined in resources like symptom-based diagnosis e-books from 2017, is critical for applying the most current standards in patient care.

This article reviews the most significant changes in the updated AJCC melanoma staging system and their implications for managing cutaneous melanoma patients in contemporary clinical practice, particularly relevant for urgent dermatology care where timely and accurate assessments are paramount.

2. Key Updates in the 8th Edition AJCC Melanoma Staging System

The 8th edition AJCC melanoma staging system TNM classifications are summarized in Tables 1–3 (compared with the 7th edition) and stage groupings are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 1.

Comparison of AJCC 7th and 8th Edition T Category (Primary Tumor) Criteriaa,b.

| 8th Edition (2018) | 7th Edition (2010) |

|---|---|

| T Category | Thickness |

| TX | N/A |

| T0 | N/A |

| Tis | N/A |

| T1 | ≤1.0 mm |

| T1a | |

| T1b | |

| 0.8–1.0 mm | With or without ulceration |

| T2 | >1.0–2.0 mm |

| T2a | >1.0–2.0 mm |

| T2b | >1.0–2.0 mm |

| T3 | >2.0–4.0 mm |

| T3a | >2.0–4.0 mm |

| T3b | >2.0–4.0 mm |

| T4 | >4.0 mm |

| T4a | >4.0 mm |

| T4b | >4.0 mm |

N/A, not applicable; TX, primary tumor thickness cannot be assessed (e.g. diagnosis by curettage); T0, no evidence of primary tumor (e.g. unknown primary or completely regressed melanoma); Tis, melanoma in situ.

aAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017:563–585).

bAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2009), published by Springer Verlag (Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Edge SB, Byrd D, Compton C, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2009: 325–344).

Table 3.

Comparison of AJCC 7th and 8th Edition M Category (Distant Metastasis) Criteriaa,b.

| 8th Edition | 7th Edition |

|---|---|

| M Category | Anatomic Site |

| M0 | No evidence of distant metastasis |

| M1 | Evidence of distant metastasis |

| M1a | Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscles, and/or nonregional lymph node |

| M1a(0) | Not elevated |

| M1a(1) | Elevated |

| M1b | Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease |

| M1b(0) | Not elevated |

| M1b(1) | Elevated |

| M1c | Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or M1b sites of disease |

| M1c(0) | Not elevated |

| M1c(1) | Elevated |

| M1d | Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a, M1b, or M1c sites of disease |

| M1d(0) | Not elevated |

| M1d(1) | Elevated |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; –, No counterpart in AJCC 7th Edition.

aAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017:563–585).

bAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2009), published by Springer Verlag (Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Edge SB, Byrd D, Compton C, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2009: 325–344).

Table 4.

Comparison of AJCC 7th and 8th Edition Clinical Stage Groupsa,b.

| 8th Edition | 7th Edition |

|---|---|

| Clinical Stage Group | T |

| 0 | Tis |

| IA | T1a |

| IB | T1b |

| T2a | N0 |

| IIA | T2b |

| T3a | N0 |

| IIB | T3b |

| T4a | N0 |

| IIC | T4b |

| III | Any T |

| IV | Any T |

aAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017:563–585).

bAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2009), published by Springer Verlag (Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Edge SB, Byrd D, Compton C, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2009: 325–344).

Table 5.

Comparison of AJCC 7th and 8th Edition Pathological Stage III Subgroupsa,b.

| 8th Edition | 7th Edition |

|---|---|

| Pathological Stage Group | T |

| IIIA | T1a/b-T2a |

| IIIB | T0 |

| IIIB | T1a/b-T2a |

| IIIB | T2b/T3a |

| IIIC | T0 |

| IIIC | T1a-T3a |

| IIIC | T3b/T4a |

| IIIC | T4b |

| IIID | T4b |

–, No counterpart in AJCC 7th Edition.

aAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017:563–585).

bAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2009), published by Springer Verlag (Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Edge SB, Byrd D, Compton C, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2009: 325–344.

2.1. Modifications to the T Category Criteria

For the 8th edition AJCC staging system, analyses of the international melanoma database stratified patients with primary melanoma without regional or distant metastasis into 8 T subcategories (T1a-T4b) (Table 1, Figure 1). These analyses included patients with T1 melanomas if they were clinically or pathologically T1N0. Patients with T2-T4 melanomas were included only if they underwent lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy, had no tumor-containing SLNs, and no microsatellites, satellites, or in-transit metastases at diagnosis or post-initial treatment (pN0 melanoma).

Figure 1.

Image alt text: Comparative survival curves illustrating melanoma-specific survival for stage I and II melanoma patients, categorized by T subcategories in both the AJCC 7th and 8th edition staging systems, highlighting the prognostic refinement achieved in the updated edition.

Primary tumor (Breslow) thickness [13] and ulceration [14,15] remain crucial prognostic factors and define T-category strata in cutaneous melanoma. In the 8th edition, tumor thickness is measured to the nearest 0.1mm, not 0.01 mm as in previous editions. The T category continues to be defined by thickness thresholds of 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mm. For example, tumors measuring 0.95 to 1.04 mm are rounded to 1.0 mm (i.e., T1b) in the 8th edition. Previously, some melanomas measuring 1.01–1.04 mm would have been staged as T2 (a: without ulceration, b: with ulceration) in the 7th edition [9,10]. The clinical effect of down-staging this small patient subset in the 8th edition is yet to be formally investigated [16].

Earlier research suggested a clinically significant threshold around 0.7–0.8 mm in T1 melanoma patients [14,16]. In the 8th edition AJCC analyses of T1 melanoma patients, multivariable analyses of factors predicting melanoma-specific survival (MSS) [tumor thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate (2 vs ≥1 mitosis/mm2)] found that tumor thickness dichotomized at ≤0.8 mm and >0.8 mm was a significant predictor of MSS, even when controlling for ulceration [10,11]. Consequently, T1a melanomas now include those ≤0.8 mm without ulceration and mitotic rate ≤1/mm2, while T1b melanomas include those ≤0.8 mm with ulceration or 0.81–1.0 mm with or without ulceration.

Mitotic rate, while still a major prognostic determinant across all melanoma thickness categories [17–21], is no longer a T-category criterion in the 8th edition but should still be documented for all patients [10]. This is an important shift for urgent care dermatology professionals to note, especially when reviewing patient records or prior staging assessments potentially based on resources like symptom-based diagnosis e-books from 2017 that may have emphasized mitotic rate in T-staging.

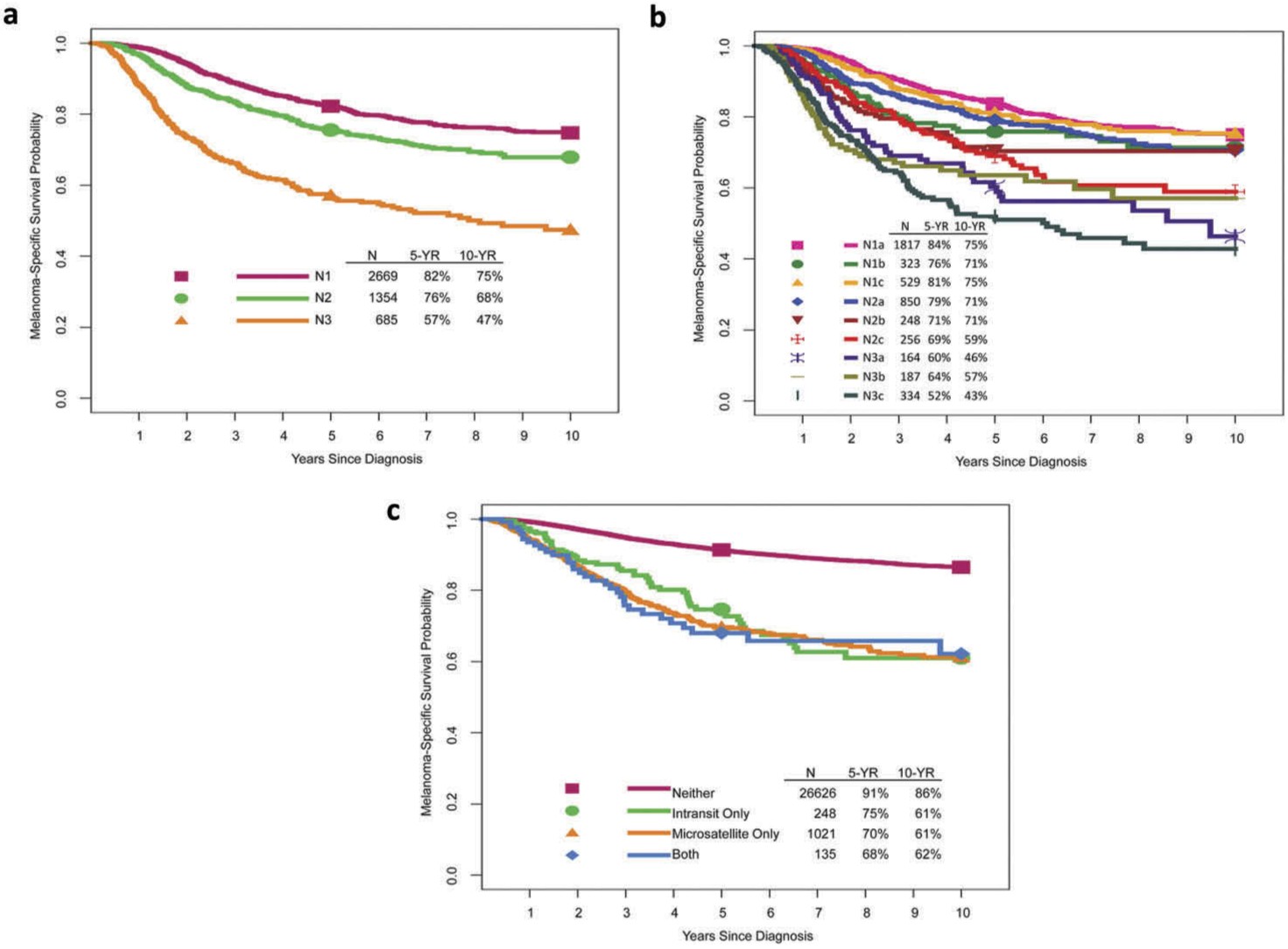

2.2. Modifications to the N Category Criteria

The 8th edition N category reflects the number and extent of tumor-involved regional nodes and non-nodal regional metastasis (Table 2, Figure 2). Regional lymph nodes are the most common initial site of melanoma metastasis. Patients without clinical or radiographic evidence of regional lymph node metastasis but with tumor-involved nodes found at SLN biopsy are classified as having ‘clinically occult’ nodal metastasis (previously ‘microscopic’ in the 7th edition). Patients with ‘clinically detected’ nodal metastasis have tumor-involved regional lymph nodes identified by clinical or radiographic examination (previously ‘macroscopic’ in the 7th edition).

Table 2.

Comparison of AJCC 7th and 8th Edition N Category (Regional Metastasis) Criteriaa,b.

| 8th Edition | 7th Edition |

|---|---|

| N Category | Number of tumor-involved regional lymph nodes and nodal metastatic burden |

| NX | Regional nodes not assessed (e.g. SLNB not performed, regional nodes previously removed for another reason) Exception: pathological N category is not required for T1 melanomas, use cN. |

| N0 | No regional metastases detected |

| N1 | 1 tumor-involved node or in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with no tumor-involved nodes |

| N1a | 1 clinically occult (i.e. detected by SLNB) |

| N1b | 1 clinically detected |

| N1c | No regional lymph node disease |

| N2 | 2 or 3 tumor-involved nodes or in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with 1 tumor-involved node |

| N2a | 2 or 3 clinically occult (i.e. detected by SLNB) |

| N2b | 2 or 3, at least 1 of which was clinically detected |

| N2c | 1 clinically occult or clinically detected |

| N3 | ≥4 tumor-involved nodes or in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with ≥2 tumor-involved nodes, or any number of matted nodes without or with in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases |

| N3a | ≥4 clinically occult (i.e. detected by SLNB) |

| N3b | ≥4, at least 1 of which was clinically detected, or presence of any number of matted nodes |

| N3c | ≥2 clinically occult or clinically detected and/or presence of any number of matted nodes |

SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; –, No counterpart in AJCC 7th Edition.

aAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th Edition (2017), published by Springer International Publishing (Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Amin AB, Edge SB, Greene, FL, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017:563–585).

bAdapted from and used with permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original and primary source for this information is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th Edition (2009), published by Springer Verlag (Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Melanoma of the Skin. In: Edge SB, Byrd D, Compton C, et al. (Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2009: 325–344.

Figure 2.

Image alt text: Melanoma-specific survival curves by N categories and presence/absence of microsatellites, satellites, or in-transit metastases, illustrating the prognostic significance of nodal involvement and regional metastasis in the AJCC 8th edition staging system.

Clinically occult nodal metastasis is more common in patients with regional metastasis at diagnosis [10] and generally associated with better survival than clinically evident disease (Figure 2b) [22–26]. Nodal status is a dominant independent survival predictor in these patients [11]. Lymphatic mapping and SLN biopsy are therefore crucial for identifying occult regional lymph node (stage III) disease in patients with clinical stage IB or II cutaneous melanoma. For urgent care dermatology, understanding these nuances in nodal staging is important when assessing patients who may require prompt referral for further oncologic evaluation.

The number of tumor-involved lymph nodes is also a significant survival predictor (Figure 2b) [11]. Historically, completion lymph node dissection (CLND) was often recommended for positive SLN biopsy, partly based on the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I) [27], as CLND provides additional nodal staging and prognostic information to guide adjuvant systemic therapy decisions. However, the recent DeCOG-SLT [28] and MSLT-II [29] trial results have shifted practice [30]. These randomized controlled trials compared immediate CLND to nodal observation in clinically occult nodal metastasis and found no overall survival difference. Future staging systems and prognostic models may need revision as fewer immediate CLNDs are performed, leading to less CLND-associated staging and prognostic information available for adjuvant therapy decisions. This evolving landscape requires urgent care dermatologists to be aware of current best practices and referral pathways.

Non-nodal regional (microsatellite, satellite, or in-transit) metastases are associated with poorer prognosis [31–34] and are also N-category criteria in the 8th Edition AJCC staging system (Table 2). Microsatellites are microscopic tumor cell foci in the skin or subcutis adjacent to but discontinuous from the primary tumor [10]. Satellite metastases are clinically evident cutaneous/subcutaneous metastases within 2 cm of the primary melanoma. In-transit metastases are clinically evident cutaneous/subcutaneous metastases >2 cm from the primary melanoma, between the primary tumor and regional lymph node basin. In 8th edition analyses, microsatellites, satellites, and in-transit metastases showed similar survival outcomes and were grouped together for staging (Figure 2c). For urgent dermatology care, recognizing these different forms of regional metastasis is crucial for accurate initial assessment and appropriate management planning.

2.3. Modifications to the M Category Criteria

Stage IV melanoma patients historically had poor prognosis, with median survival of 6–7.5 months from initial stage IV diagnosis and 5-year survival of 15–20% [35–37]. However, since the 7th edition AJCC staging system in 2010, treatment options and prognosis for stage IV melanoma have evolved rapidly with significant improvements. The Melanoma Expert Panel considered it premature to conduct a broad-based analytic initiative using recent data from patients treated in recent years for the 8th edition AJCC staging system. No M stage subgroups were proposed in the 8th edition, but M category revisions were implemented.

The distant metastasis site remains the primary M category component (Table 3). M category definitions are based on distant metastatic disease site and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. Patients with non-visceral distant metastasis (distant cutaneous, subcutaneous, nodal) are M1a and have relatively better prognosis than those with metastases to other sites [35,38,39]. Lung metastasis patients are M1b with intermediate prognosis. Non-central nervous system (CNS) visceral metastasis patients have worse prognosis and are M1c. M1c no longer includes CNS metastasis. A new M1d designation was added for patients with CNS metastasis, with or without other distant sites, to reflect their poorer prognosis [40,41] and facilitate clinical trial design and analysis. For dermatology urgent care, recognizing these distinct M categories is vital for understanding the overall disease severity and prognosis, guiding immediate management decisions and patient counseling.

Descriptors were added to each M1 subcategory to indicate serum LDH level (‘0’ for ‘not elevated’ and ‘1’ for ‘elevated’). While elevated LDH remains a negative survival predictor [42–48], it no longer automatically classifies a patient as M1c. This refinement in M staging provides more nuanced prognostic information for clinicians, including those in urgent care settings.

2.4. Clinical Stage Group Modifications

Clinical stage group definitions are unchanged between the 7th and 8th edition AJCC melanoma staging systems (Table 4). In the 8th edition, clinical staging includes microstaging after primary melanoma biopsy and clinical and radiographic evaluation (and biopsies as needed) for regional and distant metastasis. This consistency allows urgent care dermatology professionals to continue using familiar clinical staging frameworks while incorporating the updated T, N, and M category details.

2.5. Pathological Stage I and II Subgroup Modifications

Pathological stage I and II subgroupings are largely unchanged between the 7th and 8th editions (Table 5, Figure 3). The exception is the refined definition of stage IA and IB subgroups. Patients with pathological T1bN0M0 melanoma are now in pathological stage IA, not IB as in the 7th edition. This change reflects the better prognosis of patients with pT1b melanoma with pathologically negative nodes compared to those with cT1b melanoma with clinically negative nodes (some of whom have pathological positive nodes). 5-year and 10-year MSS rates in the former (pT1bN0M0) group are better (99% and 96%, respectively) than the latter (cT1bN0M0) group (97% and 93%, respectively) [11]. These subtle but important distinctions in early-stage melanoma staging, while less immediately relevant in urgent care, are important for comprehensive dermatologic understanding.

Figure 3.

Image alt text: Comparative melanoma-specific survival curves for stage I and II melanoma subgroups in the AJCC 7th and 8th edition staging systems, demonstrating the prognostic refinement within early-stage melanoma classifications in the updated edition.

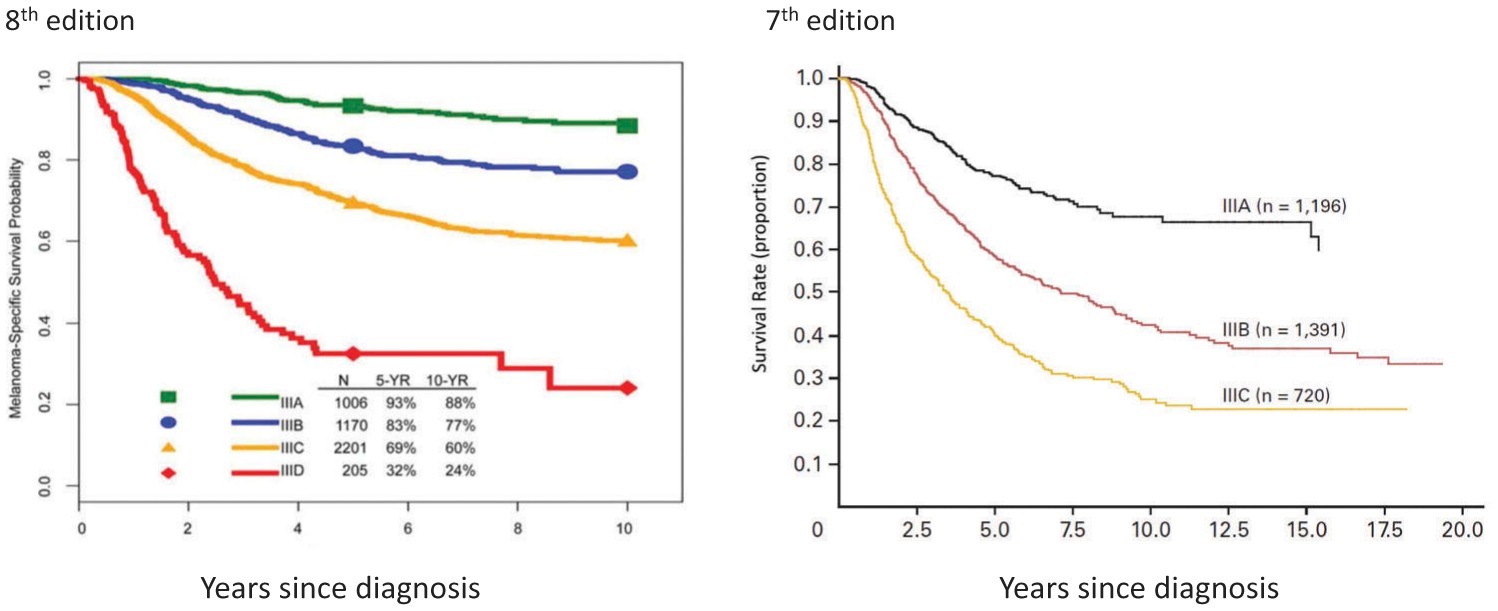

2.6. Pathological Stage III Subgroup Modifications

In the 7th edition AJCC staging system, stage III subgroups were defined by primary tumor ulceration and regional lymph node factors (number of nodes involved, microscopic vs macroscopic node involvement). For the 8th edition, the Melanoma Expert Panel hypothesized that more accurate prognostic stage subgroups could be achieved by incorporating both T category (tumor thickness and ulceration) and N-category (number of tumor-involved lymph nodes, clinically detected or occult status, and microsatellite, satellite, and/or in-transit metastases) factors. Based on these analyses, stage III melanoma patients are stratified into 4 subgroups in the 8th edition (Figures 4 and 5). This enhanced granularity in stage III classification is particularly relevant for understanding prognosis and treatment planning in more advanced regional melanoma.

Figure 4.

Image alt text: Comparison of melanoma-specific survival curves for stage III melanoma subgroups in the AJCC 7th and 8th edition staging systems, highlighting the improved prognostic stratification of regionally advanced melanoma in the updated edition.

Figure 5.

Image alt text: AJCC 8th edition pathological prognostic groups (TNM) for stage I to IV cutaneous melanoma, providing a concise visual summary of the updated staging framework and its prognostic implications across all melanoma stages.

2.7. Pathological Stage IV Group

While M category criteria were modified in the 8th edition (section 2.3), there are no stage subgroups for distant (stage IV) melanoma metastasis. Stage IV remains a broad category indicating distant spread, and while subcategories within M exist, the overall stage IV classification is not further subdivided.

2.8. Staging Patients Post Neoadjuvant Therapy

Neoadjuvant therapy is increasingly explored for locoregionally advanced and oligo-metastatic melanoma and in early phase clinical trials enabling surgical resection [49–55]. These developments have spurred enthusiasm for neoadjuvant strategies for advanced and metastatic melanoma. The 8th edition AJCC staging system includes classification approaches for patients post-definitive systemic or radiation therapy (ycTNM) or post-neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery (ypTNM) [56]. While less directly applicable in urgent care, awareness of these post-neoadjuvant staging classifications is important for dermatologists involved in comprehensive melanoma management.

2.9. Staging Patients Post Recurrence and/or Retreatment

The 8th edition AJCC staging system also includes a recurrence classification schema (rTNM), divided into ‘r-clinical’ (rcTNM) and ‘r-pathological’ (rpTNM), to better characterize disease extent during the melanoma disease course [56]. This recurrence staging framework is valuable for long-term melanoma management and follow-up, extending beyond the immediate scope of urgent dermatology care.

3. Expert Commentary

Overall, the patient cohort analyzed for the 8th edition AJCC system showed improved survival stage-for-stage compared to the 6th and 7th editions (Figures 1, 3, and 4). This is due to more accurate nodal staging and risk stratification, and also to TNM and pathological stage grouping definition changes in the 8th edition. We now discuss some implications of the 8th edition AJCC staging system for cutaneous melanoma, particularly considering the perspective of urgent care dermatology potentially utilizing resources like symptom-based diagnosis e-books from 2017 for baseline understanding and needing to update to current standards.

3.1. Implications of T Category Criteria Modifications

The T category criteria changes, particularly in T1a and T1b definitions, may increase the number of patients undergoing SLN biopsy. In the 8th edition, T1b melanoma now includes many patients previously classified as T1a in the 7th edition. In the 7th edition, melanomas of Breslow thickness 0.75 mm to 1.00 mm without ulceration were T1a. In the 8th edition, these are now 0.8 mm to 1.0 mm without ulceration and classified as T1b to reflect their poorer MSS and higher SLN metastasis risk (T1b 5–12% vs T1a 1–3%) [11,57–60]. This change emphasizes the importance of accurate thickness measurement and ulceration assessment in initial melanoma evaluation, even in urgent care settings, as it directly impacts staging and subsequent management decisions. Dermatology professionals in urgent care should be aware of these refined T-staging criteria to ensure appropriate referral for SLN biopsy consideration.

3.2. Implications of N Category Criteria and Stage III Subgroup Modifications

As in the 7th edition, significant prognostic heterogeneity exists within stage III regional disease by N category in the 8th edition patient cohort (Figures 2 and 4). The Melanoma Expert Panel enhanced granularity in the N category by clarifying definitions and increasing subcategories from 5 to 9 to reflect factors associated with prognosis: (1) regional node tumor involvement extent [clinically occult (N1a, N2a, N3a) vs clinically detected (N1b, N2b, N3b)], (2) number of tumor-involved regional nodes, and (3) presence of microsatellites, satellites, or in-transit metastases (N1c, N2c, N3c). These refined N-staging details are crucial for accurate risk assessment and treatment planning in regional melanoma.

The 8th edition created 4 stage III subgroups (vs 3 in the 7th) incorporating primary tumor features and regional node tumor involvement extent (Table 5). For example, in the 7th edition, patients with up to 3 clinically occult tumor-involved regional lymph nodes and melanoma of any Breslow thickness were stage IIIA or IIIB based on primary melanoma ulceration. In the 8th edition, patients with up to 3 clinically occult tumor-involved regional lymph nodes can be IIIA, IIIB, or IIIC depending on primary tumor thickness and ulceration. This more granular stage III classification allows for better risk stratification and tailored management strategies.

In the 8th edition analyses, stage III patients showed widely variable prognosis, from 93% 5-year MSS for stage IIIA to 32% for stage IIID disease (Figure 4) [11]. In comparison, stage III patients in the 7th edition had overall worse prognosis, with 5-year MSS for stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC disease of 78%, 59%, and 40%, respectively [8]. These significant prognostic differences, especially in stages IIIA and IIIB, between the 7th and 8th editions have major implications for clinical decisions, patient counseling, and risk stratification for adjuvant therapy consideration. When interpreting adjuvant therapy clinical trials [6,7,61–64], it’s important to recognize that trial participants with stage IIIA/B/C (7th edition) are higher risk and have worse prognosis than patients with similar stage III subgroups in the 8th edition. For urgent care dermatology, understanding these stage III nuances is important for appropriate referral and communicating initial risk assessments to patients.

3.3. Implications of M Category Criteria Modifications

In the 8th edition AJCC staging system, stage IV patients are categorized by disease site (M1a: non-visceral distant cutaneous, subcutaneous, or nodal sites; M1b: lung; M1c: non-CNS visceral sites; and M1d: CNS sites) (Table 3). Given the poor prognosis of CNS metastases in melanoma, this group has often been excluded from clinical trials, or CNS disease presence was a protocol inclusion/stratification criterion [2,6–7,64–71]. The new M1d designation for CNS metastasis better reflects their poorer prognosis and facilitates clinical trial design and analysis. For urgent care dermatology, recognizing the M categories, especially M1d for CNS involvement, can inform immediate management and referral decisions for patients presenting with signs of advanced disease.

4. Five-Year View

Comprehensive knowledge of prognostic factors and cutaneous melanoma staging is crucial for initial patient assessment, treatment planning, surveillance strategies, and clinical trial design and analysis. The 8th edition AJCC melanoma staging system is a contemporary standardized system for patient risk stratification and treatment guidance. Recent clinical trials of adjuvant targeted and immune checkpoint therapies in stage III and IV melanoma [6,7] and immediate CLND vs nodal observation in sentinel-node metastasis [29] are practice-changing. Looking ahead, fewer immediate CLNDs are likely, reducing staging and prognostic information. Adjuvant systemic therapy decisions will need to be made without CLND-associated staging and prognostic data. Future staging systems and prognostic models will need to reflect these practice changes. For urgent care dermatology, staying updated with these evolving treatment paradigms and staging systems is essential for providing optimal initial care and referral pathways. Resources like updated dermatology e-books, building upon earlier symptom-based diagnostic approaches (e.g., a 2017 edition), will be crucial for continuous professional development and ensuring adherence to current best practices in melanoma management.

Key issues.

- Staging significantly impacts prognostic assessment, treatment decisions, and clinical trial planning, design, and analysis.

- The AJCC melanoma staging system is the most widely accepted approach to staging and classification at initial diagnosis. The 8th edition was implemented in the US on January 1, 2018.

- Primary tumor thickness and ulceration remain important prognostic factors and define T-category strata in the 8th edition AJCC staging system. Mitotic rate is no longer a T-category criterion but should still be documented.

- The N category reflects both the number and extent of tumor-involved regional nodes and non-nodal regional metastasis.

- Stage III groupings are based on T and N category criteria and increased from three to four subgroups.

- Distant metastasis site remains the primary M category component. A new M1d designation was added for CNS metastasis, reflecting poorer prognosis.

- DeCOG-SLT and MSLT-II trials reported no MSS difference between immediate CLND and nodal observation for sentinel-node metastasis, changing practice and potentially reducing valuable staging and prognostic information. Future staging systems and prognostic models will need to reflect these practice shifts.

Funding

This manuscript has been supported in part by The Michael and Patricia Booker Research Endowment; The Robert and Lynne Grossman Family Foundation; and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Melanoma Moon Shots Program.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

JE Gershenwald has served on advisory boards for Merck, Syndax, and Castle Biosciences, unrelated to the content of this article. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.