Introduction

Urticaria, commonly known as hives, is a condition rooted in mast cell activation, clinically manifesting as wheals, angioedema, or both, in the absence of systemic symptoms. Globally prevalent, urticaria poses a significant health burden, particularly in chronic cases lasting beyond six weeks. While diagnosing urticaria is typically straightforward, it is crucial to exclude conditions presenting with similar urticarial lesions, notably urticarial vasculitis and autoinflammatory syndromes. These conditions often exhibit atypical features such as prolonged lesion duration, bruising, fever, malaise, and arthralgia, prompting clinicians to consider diagnoses beyond typical urticaria. This article proposes a diagnostic approach based on these atypical characteristics, the presence or absence of systemic symptoms, skin histopathology, and relevant blood parameters to aid in the Urticaria Differential Diagnosis.

Urticaria is defined by mast cell-dependent wheals and/or angioedema without systemic involvement. It can be categorized as acute or chronic, with chronic urticaria characterized by recurrent signs and symptoms persisting for more than six weeks, further classified into spontaneous and inducible forms. Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), the most prevalent type of chronic urticaria (CU), is marked by transient wheals, angioedema, or both, lacking identifiable triggers. Wheals are pruritic, pink or pale swellings in the superficial dermis, resolving within 24 hours.

Acute urticaria is generally a common, self-limiting condition. Although often idiopathic, common causes include infections, drugs, food, and hymenoptera venom allergies. Food components can act as allergens (like tropomyosin in seafood, ovalbumin in eggs) or pseudoallergens (non-protein molecules such as salicylates, benzoic acid). Physical activity can also trigger acute urticaria, as seen in exercise-induced urticaria. Oral allergy syndrome represents a localized mucosal allergic reaction in pollen-sensitized individuals due to IgE cross-reactivity between pollen allergens and plant foods. It is the most common food allergy; while symptoms are typically mild and localized, they can escalate to generalized reactions with cutaneous manifestations, including urticaria.

Chronic urticaria affects 0.5%–3% of the population and can persist for months to years. CSU often lacks a clear cause, but autoimmunity or autoallergy is implicated in many cases, with external factors like drugs, infections, or stress potentially exacerbating it. Inducible urticaria comprises diverse conditions triggered by physical stimuli (cold, heat, pressure, light, etc.) or exercise (cholinergic urticaria). Patients usually identify triggers, but physician confirmation and reactivity threshold establishment are important. Inducible urticaria can also present with systemic symptoms, occasionally life-threatening, particularly in cold-induced or cholinergic variants.

Differential Diagnosis In Acute Urticaria

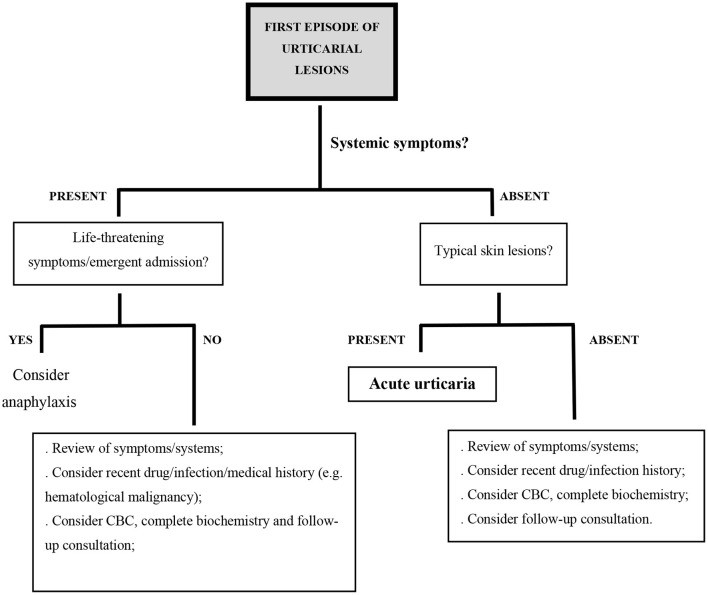

Initially, differentiating between acute and chronic urticaria might be challenging. In both scenarios, when evaluating a patient with presumed urticaria, especially in the first episode of urticarial lesions without systemic symptoms, it’s crucial to consider alternative diagnoses if atypical characteristics are present. Atypical features of urticarial lesions include infiltration, prolonged duration (>24 hours), coexistence with other skin lesions (papules, vesicles, hemorrhages), resolution with pigment changes or scaling, symmetrical distribution, and typically absent angioedema. The presence of systemic symptoms like fever, malaise, or arthralgia is also less common in typical urticaria and should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses. Several systemic disorders can manifest with urticarial lesions, including urticarial vasculitis, connective tissue diseases, hematologic diseases, and autoinflammatory syndromes, all falling under the differential diagnosis of urticaria. Angioedema is frequently associated with CSU, occurring in over 50% of cases and adding to the disease burden, but isolated angioedema, especially with systemic symptoms, suggests bradykinin-mediated angioedema.

When evaluating a patient presenting with presumed acute urticaria, consider the following differential diagnoses if atypical features are observed:

Polymorphic Light Eruption

Polymorphic light eruption (PLE) typically emerges in spring, characterized by symmetrically distributed, itchy, polymorphic, erythematous skin lesions appearing post-sun exposure and lasting several days.

Maculopapular Cutaneous Mastocytosis

Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis is identified by multiple hyperpigmented macular or maculopapular lesions that urticate rapidly upon rubbing.

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid often begins with a non-specific pruritic rash, sometimes resembling urticaria, but the lesions persist for days and can progress to bullae. It can mimic urticarial dermatoses in pregnancy, such as pemphigoid gestationis.

Erythema Annulare Centrifugum

Erythema annulare centrifugum is marked by solitary or multiple erythematous, ring-shaped, polycyclic plaques that expand peripherally and may exhibit slight scaling at the advancing edge.

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is triggered by progesterone hypersensitivity. Skin lesions, varying from wheals to eczema, cyclically worsen premenstrually.

Urticarial Dermatitis

Urticarial dermatitis primarily affects older adults, presenting with intensely pruritic eczematous and urticarial lesions, concurrently or sequentially. It is often treatment-resistant and can be idiopathic or an initial manifestation of conditions like bullous pemphigoid or drug eruptions. These entities can also recur, contributing to the differential diagnosis of both acute and chronic urticarial lesions.

In cases of acute urticarial lesions accompanied by systemic symptoms, further differential diagnoses should be considered.

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis with acute urticaria arises post-allergen exposure (food, medications, insect venom), triggering vasoactive mediator release from mast cells and basophils, often via an IgE-mediated pathway. Anaphylaxis is likely with rapid onset of generalized wheals and/or angioedema plus respiratory symptoms, hypotension, syncope, gastrointestinal symptoms, incontinence, or uterine cramps. Acute urticaria lasting hours or days is unlikely to develop into anaphylaxis.

Maculopapular Drug Exanthem

Maculopapular drug exanthem, a T-cell mediated reaction, can occur days to weeks after starting nearly any drug. It typically presents as a symmetrical eruption of confluent red macules and urticarial papules, starting on the upper trunk and spreading distally, lasting several days and evolving into desquamation, sometimes with systemic symptoms.

Viral Exanthem

Viral exanthems can manifest as macular, maculopapular, urticarial, or vesicular reactions, lasting a few days and potentially associated with mucosal lesions, fever, or other systemic symptoms.

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme is an acute eruption of dull red, macular, papular, or urticarial lesions with a target appearance, preferentially on distal extremities, appearing in crops over a few days, slowly enlarging, and fading in 1–2 weeks. Erythema multiforme major includes mucosal erosions and systemic symptoms like fever. Urticaria multiforme, sometimes challenging to differentiate from erythema multiforme, is a benign hypersensitivity response in children, with acute, transient urticarial lesions of dusky quality.

Sweet’s Syndrome

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) features fever and abrupt onset of painful, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules, often pseudovesicular, persisting for days to weeks.

Differential Diagnosis In Chronic Urticaria

For patients reporting intermittent wheal crops for over six weeks, often with angioedema, chronic urticaria (CU) is probable. However, systemic symptoms or atypical features necessitate ruling out other diagnoses. Systemic symptoms should raise suspicion that the urticarial rash is not urticaria but a systemic syndrome with urticaria-like skin lesions. These alternative diagnoses should also be considered in patients unresponsive to standard CU treatment.

When considering chronic urticaria in the differential diagnosis, especially when atypical features or systemic symptoms are present, consider the following conditions:

Urticarial Vasculitis

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is defined by recurrent urticarial lesions persisting over 24 hours, with leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology. Skin lesions evolve in size and shape, can be painful, and often resolve with bruising or hyperpigmentation. UV may also include angioedema, purpura, and systemic manifestations such as arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, ocular and renal issues, or respiratory symptoms. It is often idiopathic but can be linked to drugs, infections, malignancy, or autoimmunity. Diagnosis relies on skin histopathology, supplemented by lab tests including complete blood count, serum creatinine, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), urinalysis, complement studies (C1q, C3, C4), anti-C1q antibody assays, and connective tissue disease or viral infection tests. Based on complement levels, UV is categorized into normocomplementemic (NUV), hypocomplementemic (HUV), or hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS). NUV accounts for about 80% of UV cases and can be clinically and histopathologically difficult to distinguish from severe CSU. HUV and HUVS are more severe, often associated with longer disease duration and underlying disorders. Anti-C1q antibodies are found in about 55% of HUV patients but are not specific.

Hypereosinophilic Syndromes

Hypereosinophilic syndromes are a diverse group of disorders characterized by persistent, marked blood eosinophilia for over six months, linked to eosinophil-induced organ damage, excluding other causes of hypereosinophilia like parasitosis. Common, nonspecific cutaneous manifestations include urticarial lesions, intensely itchy erythematous papules and nodules, or eczematous lesions. Mucosal ulcerations are also possible. Skin histopathology often shows dermal eosinophilic infiltration with flame figures.

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) is a recently recognized entity encompassing primary (clonal), secondary (environmental trigger-responsive), and idiopathic etiologies, affecting cutaneous, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurologic systems. Cutaneous manifestations include urticaria and angioedema, potentially with anaphylaxis, flushing, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, or tachycardia. MCAS remains controversial with no definitive diagnostic criteria and is not universally accepted. Some experts suggest the term MCAS be reserved for idiopathic cases, though some idiopathic cases later are found to be clonal mast cell proliferative disease.

Autoinflammatory Urticarial Syndromes

Autoinflammatory urticarial syndromes are rare, debilitating chronic diseases featuring recurrent urticarial lesions with neutrophilic infiltrates on skin biopsy, neutrophilic leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR, serum amyloid A). Lesions are typically flat, erythematous wheals lasting up to 24 hours, mainly on the trunk and/or extremities, unresponsive to H1-antihistamines. Pruritus may be absent, and lesions can be painful. Diagnosis is often delayed by several years. These syndromes can be hereditary or acquired. Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes are hereditary autoinflammatory conditions with episodes of fever, urticaria-like rash, fatigue, headaches, arthralgia, arthritis, myalgia, sensorineural hearing loss, ocular inflammation, and/or bone lesions, often starting in early childhood. Inflammation results from innate immunity dysregulation and interleukin-1 overproduction. Schnitzler syndrome, an acquired autoinflammatory disease typically starting later in life, includes recurrent fever, urticarial lesions, arthralgia, arthritis, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and monoclonal gammopathy (mostly IgM). About 15% of patients develop lymphoproliferative disorders. Pathophysiology is unclear, but IL-1 mediation is suspected. Anti-IL1 drugs can effectively manage the disease, but untreated chronic inflammation may lead to amyloidosis. Adult-onset Still disease, a rare systemic inflammatory disease, usually presents as a triad of high fever, arthralgia, and an evanescent erythematous rash with fever spikes. Urticarial eruptions with neutrophilic infiltrates occur in about 22% of cases. IL-1 is implicated in pathogenesis, and serum ferritin is usually significantly elevated. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis has been reported as the presenting feature in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Gleich syndrome (episodic angioedema with eosinophilia) is characterized by cyclic episodes of angioedema, wheals, fever, weight gain, and dramatic eosinophilia.

If autoinflammatory disease is suspected, testing for elevated inflammatory markers, serum protein electrophoresis for monoclonal gammopathy, urinalysis for proteinuria (renal amyloidosis), and skin biopsy for neutrophil-rich infiltrates are indicated. For suspected hereditary autoinflammatory disease, genetic testing for relevant mutations should be considered.

Differential Diagnosis Of Angioedema Without Wheals

Angioedema without wheals presents a distinct clinical picture necessitating a separate differential diagnosis. Prompt diagnosis is crucial as effective treatment depends on the specific subtype and the primary mediator causing increased vascular permeability.

When considering angioedema without wheals in the differential diagnosis, it is important to distinguish between mast cell-mediated and bradykinin-mediated angioedema, as well as hereditary and acquired forms.

Mast Cell-Mediated Angioedema

Mast cell-mediated angioedema is triggered by histamine and other mast cell mediators. It responds well to H1-antihistamines, glucocorticoids, and epinephrine. Approximately 10% of CSU patients experience angioedema without wheals. In this context, angioedema can last up to 72 hours and commonly starts on the head or neck in the early morning. Mast cell-mediated angioedema can also occur in acute urticaria or anaphylaxis. IgE-independent mast cell activation mechanisms may also be involved in drug-induced angioedema, such as vancomycin or fluoroquinolones via MRGPRX2, or NSAIDs via arachidonic acid metabolism alterations.

Bradykinin-Mediated Angioedema

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema is caused by bradykinin, which promotes vasodilation and increases vascular permeability. Bradykinin-induced phosphorylation of endothelial cadherins disrupts endothelial cell adhesions, leading to plasma leakage and edema in the dermis and subcutis (angioedema) without wheals. This type of angioedema responds poorly to standard CU treatments, lasts 3–5 days, and can cause life-threatening laryngeal and oropharyngeal swelling, as well as gastrointestinal edema mimicking surgical emergencies.

Drugs, particularly ACE inhibitors and less frequently angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARA-II), DPP-IV inhibitors, and sacubitril, which interfere with kinin degradation, are associated with bradykinin-mediated angioedema. ACE inhibitor-associated angioedema is relatively common and can occur months to years after starting the medication. It typically resolves slowly after drug cessation, but recurrence can occur for months post-withdrawal.

Hereditary Angioedema

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) can manifest in early life or adulthood and is primarily due to autosomal dominant mutations in the C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) gene. Quantitative or functional C1-INH deficiency leads to complement consumption (low C4) and uncontrolled kallikrein and kininogen activation, resulting in bradykinin overproduction. HAE attacks can be spontaneous or triggered by minor stimuli like trauma or stress and may be life-threatening. HAE can also occur with normal C1-INH due to mutations in other genes involved in bradykinin production, such as factor XII, plasminogen, angiopoeitin-1, and kininogen-1 genes; many hereditary angioedema cases remain unclassified. Acquired C1-INH deficiency-related angioedema is often associated with lymphoproliferative or autoimmune disorders, causing continuous classical complement pathway activation and C1-INH depletion. Patients with recurrent angioedema without wheals, unresponsive to standard CU treatment, and not taking ACE inhibitors should be screened for complement deficiency. Low C4 levels necessitate C1-INH quantification and functional assessment.

Angioedema must also be differentiated from other conditions causing swelling, especially when standard angioedema treatments fail.

Granulomatous Cheilitis

Granulomatous cheilitis is characterized by intermittent lip swelling initially, progressing to persistent lip and sometimes facial swelling due to granulomatous inflammation of unknown etiology.

Cellulitis and Erysipelas

Cellulitis and erysipelas involve acute dermal and subcutaneous tissue inflammation from bacterial infection, causing bright red, swollen, painful, and hot areas, typically with fever and systemic symptoms.

Wells Syndrome

Wells syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis) presents with swelling resembling cellulitis.

Periorbital Swelling

Periorbital swelling resembling angioedema of the eyelids can occur in autoimmune hypothyroidism, dermatomyositis, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis, particularly from hair dye allergy, may be misdiagnosed as facial angioedema. Differentiation can be challenging initially, but contact dermatitis swelling spreads with gravity, and epidermal changes like vesicles, scale, and crusting are present and resolve faster with glucocorticoids. Patch testing confirms hypersensitivity to p-phenylenediamine and related hair dye chemicals.

Photoallergy

Photoallergy, from systemic drugs or contact photoallergens (NSAIDs or sunscreens), usually appears hours to days post-exposure, presenting as dermatitis, sometimes with significant edema, and can be mistaken for angioedema.

Conclusion

Differentiating common urticaria from urticarial syndromes or other dermatologic conditions presenting with urticarial lesions and/or angioedema is a significant diagnostic challenge. In addition to thorough clinical history and skin lesion evaluation, skin biopsy, guided by clinical insight, is invaluable in these scenarios. Assessing serum inflammatory parameters like CRP and ESR, leukocytosis, or clinically relevant biomarkers (C1q, C3, C4, ferritin, protein immunofixation, specific IgE, tryptase, ferritin) can further aid in resolving the differential diagnosis of urticarial lesions and ensure accurate urticaria differential diagnosis.

Author Contributions

AM and MG contributed equally to manuscript writing. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.