Posterior hip pain, while less prevalent than anterior or lateral hip discomfort, represents a significant challenge in orthopedic diagnosis. For specialists in automotive repair at xentrydiagnosis.store, understanding complex diagnostic pathways is paramount. Similarly, in the realm of human anatomy, pinpointing the source of posterior hip pain requires a meticulous approach. Patients often present with vague symptoms, complicating the journey to an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment plan. This article, crafted for the English-speaking audience and optimized for search engines, delves into the common diagnoses behind posterior hip pain, aiming to provide a comprehensive and insightful resource for healthcare professionals.

Understanding the Landscape of Posterior Hip Pain

Hip injuries, though not as common as knee or ankle issues, are a noteworthy concern, particularly in athletic populations. Athletes engaged in sports like golf, soccer, and dance are especially susceptible. Historically, conservative treatment was the standard approach for most athletic hip injuries, irrespective of the specific diagnosis. However, the field of hip pathology has witnessed substantial growth in recent years. Advances in arthroscopic surgical techniques and implant technology have significantly improved athletes’ ability to return to their sports post-hip injury. Furthermore, progress in medical imaging technologies has equipped clinicians with enhanced tools to understand the origins of hip disorders and achieve more precise diagnoses across various pathologies. Paradoxically, despite these advancements, posterior hip injuries may be underreported due to diagnostic ambiguity.

Hip pain classification can be approached in several ways, considering the pain’s location (anterior, posterior, lateral, medial/groin), its relation to the joint (intra-articular, extra-articular), and its onset (acute/traumatic, insidious). Notably, posterior hip pain, the least common among hip pain types, often originates from sources outside the hip joint itself.

Recent progress in understanding hip anatomy, how diseases develop (pathophysiology), and treatment options has empowered healthcare providers to diagnose hip injuries in athletes more effectively and to tailor treatments appropriately. While extensive knowledge exists regarding the posterior hip’s anatomy and function, a comprehensive review detailing the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic tools, and treatment strategies for posterior hip pain management has been lacking – until now.

Anatomical Foundations of Posterior Hip Pain

The hip joint is a marvel of biomechanics, enduring forces of 6 to 8 times body weight during everyday activities like walking and jogging. In high-impact sports, these loads intensify, making the hip joint vulnerable to injury. A solid grasp of hip anatomy and surrounding structures is crucial for healthcare providers to navigate the often-complex clinical presentations and arrive at accurate diagnoses and effective treatment strategies.

The hip joint’s architecture involves a complex interplay of bones, muscles, and connective tissues. The bony framework includes the acetabulum, formed by the ischium, ilium, and pubis, and the femoral head. These articulate to create a spheroidal, multi-axial ball-and-socket joint. Encapsulating this articulation is a fibrous capsulolabral structure, comprising the labrum and various ligaments, providing crucial support. The iliofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments reinforce the anterior joint, while the ischiofemoral ligament supports the posterior aspect, each preventing excessive joint translation during movement.

The hip’s bony structure and ligamentous support dictate its range of motion: flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation (summarized in Table 1). Muscles are the engines of these movements. The iliopsoas is the primary hip flexor, while the gluteal muscles are key for extension (gluteus maximus), abduction (gluteus medius and minimus), internal rotation (gluteus minimus), and external rotation (gluteus maximus). The anterior thigh compartment houses muscles like the sartorius, tensor fascia lata, quadriceps femoris, pectineus, and iliopsoas. The medial compartment includes the pectineus and adductor muscles (adductor longus, brevis, magnus, and gracilis). The posterior compartment contains the hamstrings (biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus). Another significant muscle in hip external rotation is the piriformis. Its proximity to the sciatic nerve makes it a frequent source of posterior hip pain when inflamed.

Table 1: Functions of Major Hip Muscles

| Action | Muscle |

|---|---|

| Flexion | Iliopsoas, Rectus Femoris, Pectineus, Sartorius, Tensor Fascia Lata |

| Extension | Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, Semimembranosus, Semitendinosus |

| Adduction | Adductor Longus, Brevis, Magnus, Gracilis, Pectineus |

| Abduction | Gluteus Medius, Gluteus Minimus |

| Internal Rotation | Gluteus Minimus, Tensor Fascia Lata |

| External Rotation | Gluteus Maximus, Piriformis, Superior Gemellus, Obturator Internus, Inferior Gemellus, Obturator Externus, Quadratus Femoris |

Because the femoral and obturator nerves primarily innervate the articular hip, intra-articular pathologies often manifest as anterior or medial hip pain. Conversely, posterior hip pain is typically linked to extra-articular conditions. However, pain patterns can be complex, sometimes radiating beyond typical distributions. Hilton’s law explains this phenomenon: the nerve supplying a joint also innervates the muscles moving that joint and the overlying skin. This suggests hip joint pain can often be referred pain from muscles. The hip receives innervation from the lumbosacral plexus (L2-S1), predominantly from the L3 nerve root. Given the L3 dermatome’s distribution, hip pathology usually causes anterior or medial thigh pain. Posterior thigh pain is less commonly a sign of intra-articular hip issues.

Bursae around the hip, such as the trochanteric, iliopsoas, and ischial tuberosity bursae, are also crucial anatomical features and potential pain sources. These fluid-filled sacs minimize friction between soft tissues and bony prominences during movement. However, inflammation (bursitis) can cause significant pain. Ischial bursitis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of posterior hip pain, especially when direct palpation elicits severe discomfort.

Diagnostic Journey: History, Physical Examination, and Imaging

History and Physical Examination: The Cornerstones of Diagnosis

A comprehensive patient history and thorough physical examination are indispensable for accurately diagnosing and treating posterior hip pain. Given the hip’s proximity to vital structures, including reproductive and gastrointestinal organs, systemic symptoms alongside hip pain necessitate immediate investigation for potential infection, cancer, or inflammatory arthritis. Alarming symptoms include fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, drug abuse history, cancer history, or immunocompromised status. Trauma history requires ruling out hip fracture.

Once systemic issues and fractures are excluded, a detailed pain history is essential, focusing on pain location (anterior, posterior, lateral, or medial/groin) and characteristics. Onset, aggravating activities, patient age, activity level, and pre-existing medical conditions are critical factors.

The physical examination should be methodical, examining both hips and following a stepwise approach: observation, palpation, range of motion testing, stability assessments, and strength evaluations in all planes. Gait analysis is crucial, noting antalgic or Trendelenburg gait or signs, and observing transitions between standing, sitting, and lying. Iliac crest height symmetry and leg length should be assessed, as discrepancies can contribute to lower back, hip, and sacroiliac (SI) joint pain. Palpation should focus on hip bursae, common pain sources when inflamed, particularly the ischial bursa in posterior hip pain cases.

Range of motion should be tested bilaterally, starting with the asymptomatic hip to avoid guarding due to pain. Passive and active internal rotation, external rotation, flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction should be measured using a goniometer. Normal ranges are approximately 35°, 45°, 120°, 30°, 45°, and 20°, respectively. The Thomas test evaluates hip flexion contractures. A positive test, indicated by the inability to fully extend the examined leg when the opposite knee is flexed to the chest, suggests a contracture. Strength testing should cover internal and external rotation, adduction (seated or prone), abduction (lateral lying), extension (standing), and flexion (seated and supine). Logrolling and impingement tests, while not specific to posterior hip pathology, help rule out other hip pain etiologies like femoroacetabular impingement.

Specific tests like Trendelenburg, Ober, FABER (Patrick), and Thomas tests are valuable. The Trendelenburg test assesses gluteus medius strength. Pelvic drop on the unsupported leg during single-leg stance indicates gluteus medius weakness on the stance leg.

The FABER test differentiates lumbar spine from primary hip pathology. Posterior hip pain during this test (flexion, abduction, external rotation with ankle on opposite knee and pressure on the abducted knee) suggests SI joint involvement. Groin pain without motion loss points more towards intra-articular hip pathology (88% sensitivity for intra-articular issues in athletes). Intra-articular hip pain is often described using the “C-sign,” where patients cup their hip with thumb and forefinger. The posterior impingement test, performed with hip extension and external rotation, is positive if it reproduces posterior hip pain. A thorough lumbosacral examination, including inspection, palpation, range of motion, neurosensory assessment, and straight leg raises, is essential to exclude lumbosacral contributions to hip pain.

Imaging Studies: Visualizing the Source of Pain

Imaging modalities, including radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans, fluoroscopically and ultrasound-guided injections, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance arthrography, are valuable tools in evaluating posterior hip pain. Radiographic series should include standard anterior-posterior pelvis views. Lateral hip views like cross-table lateral, frog-leg lateral, Dunn lateral, and false profile views are also utilized. Radiographs are crucial when bony pathology is suspected due to trauma, osteoporosis, cancer risk, or steroid/alcohol use. Careful assessment of the posterior inferior hip joint is vital, as early arthritis can manifest there even with a normal superior joint space. CT scans, especially with 3D reconstructions, offer detailed information on femoral version and osseous abnormalities. MRI is the preferred imaging for athletes, providing detailed views of soft tissue structures around the hip. Fluoroscopically guided hip injections with anesthetic can differentiate intra-articular from extra-articular pathology. Ultrasound-guided injections target iliopsoas and trochanteric bursae. Hip arthroscopy is considered the definitive diagnostic procedure for intra-articular hip pathology.

Differential Diagnosis: Unmasking the Causes of Posterior Hip Pain

Posterior hip pain is the least common type of hip pain compared to anterior, lateral, and medial pain. When evaluating posterior hip pain, consider structures around the hip, especially the lower back and pelvic nerves. A deep understanding of hip anatomy is critical for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. Fractures must also be considered, particularly in high-risk groups like long-distance runners, individuals with osteoporosis, and those with trauma history or falls. Table 2 outlines a differential diagnosis for general hip pain.

Table 2: Differential Diagnosis of Hip Pain

| Classification | Potential Etiologies |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Lateral Hip Pain | Greater Trochanteric Bursitis, Gluteus Medius Dysfunction, Iliotibial Band Syndrome, Meralgia Paresthetica |

| Anterior Hip Pain | Osteoarthritis, Hip Flexor Tendinopathy, Iliopsoas Bursitis, Hip Fracture, Stress Fracture, Acetabular Labral Tear, Avascular Necrosis of Femoral Head |

| Posterior Hip Pain | Referred from Lumbar Spine, Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction, Hip Extensor or Rotator Strain, Proximal Hamstring Rupture, Piriformis Syndrome |

| Medial Hip Pain | Groin Pain |

| Location about Joint | |

| Intra-articular | Labral Tears, Loose Bodies, Femoroacetabular Impingement, Capsular Laxity, Ligamentum Teres Rupture, Chondral Damage |

| Extra-articular | Iliopsoas Tendonitis, Iliotibial Band, Gluteus Medius/Minimus, Greater Trochanteric Bursitis, Stress Fracture, Abductor Strain, Piriformis Syndrome, SI Joint Pathology |

| Onset | |

| Acute | Muscle Strain, Contusion (Hip Pointer), Avulsions and Apophyseal Injuries, Hip Dislocation/Subluxation, Acetabular Labral Tears and Loose Bodies, Proximal Femur Fractures |

| Insidious | Sports Hernias and Athletic Pubalgia, Osteitis Pubis, Bursitis, Snapping Hip Syndrome, Stress Syndrome, Osteoarthritis |

| Systemic Causes | Cancer, Infection, Inflammatory Arthritis |

| Mimickers of Hip Pain | Athletic Pubalgia, Sports Hernia, Osteitis Pubis |

| Referred Pain | Lumbar Spine, Degenerative Disc Disease |

The most common causes of posterior hip pain include:

- Referred pain from the lumbar spine

- Sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction

- Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain

- Proximal hamstring rupture

- Piriformis syndrome

- Early arthritis

These are detailed further in Table 3. Table 4 provides examples of therapeutic exercises for these conditions, often suitable for home practice.

Table 3: Differential Diagnosis of Posterior Hip Pain

| Diagnosis | Findings |

|---|---|

| Referred Pain from Lumbar Spine | Low back pain, Pain elicited with isolated lumbar flexion/extension, Radicular symptoms |

| Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction | Pelvic asymmetry on examination, Posterior hip or buttocks pain (especially runners) |

| Hip Extensor or Rotator Muscle Strain | History of overuse, Acute injury, Pain with resisted muscle testing, Tenderness to palpation over gluteal muscles |

| Proximal Hamstring Rupture | Posterior hip pain, Signs of muscle weakness and sciatica |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Pain in the sciatic nerve distribution (low back, buttock, leg), Pain exacerbated by stooping or lifting, Pain with straight leg raise |

Table 4: Examples of Home Exercises

| Condition | Exercise | Instructions |

|---|---|---|

| Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction | Knee to Chest | Lie flat, bring knee to chest with hands, alternate knees. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. |

| Prone Press-up | Lie prone, press up with hands while keeping pelvis on floor/table. Hold for 30 seconds, repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Nonweightbearing Lumbar Rotation | Lie flat with feet flat on table/floor, rock both knees back and forth in small movements. Perform for 30 seconds, 3 sets. | |

| Extensor/Rotator Strain | Hip Abduction | Lie on side (injured leg on top, bottom knee slightly bent), lift top leg up leading with heel, hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. |

| Hip Abduction Alternate | Get on hands and knees, lift knee up and out to the side from the hip, hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, alternate legs, 3 sets. | |

| Hip Abduction with Tubing | Sit, place resistance tubing around thighs above knees, spread legs against the resistance, hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Hamstring Strain/Rupture | Supine Stretch | Lie flat, support back of knee with hand or towel, and attempt to extend knee so that plantar surface of foot faces ceiling. Hold for 20 to 30 seconds. |

| Hip Extension | Lie prone, raise up leg from behind the hip while keeping knee straight, hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Isometric Strengthening | Lie supine, flex knee, and push heel into floor/table with force, hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Hamstring Curls | Lie prone, flex knee to 90°, hold for 5 seconds, slowly extend leg until flat. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Piriformis Syndrome | Prone Hip Extension | Lie prone with pillow under hips, bend knee, and contract gluteal muscles, then lift leg off surface 6 in. (15 cm) (leg on surface stays straight), hold for 5 seconds. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. |

| Resisted Abduction with Resistance Band | Stand sideways near doorway with resistance band around ankle away from door (place other end of resistance band into doorway and close), then extend leg out to side with knee straight. Repeat 10×, 3 sets. | |

| Hamstring Stretch Seated | Sit with heel of injured leg resting on a 15-in. (38-cm) platform with knee extended, then lean forward at hips until stretch is felt (do NOT bend at waist or shoulders). Hold for 30 seconds, repeat 3×. | |

| Gluteal Stretch | Lie flat with knees bent and ankle of one leg over knee of other. Then hold thigh of bottom leg and pull toward chest. Hold for 30 seconds, repeat 3×. |

Referred Pain from the Lumbar Spine: A Primary Culprit

Referred pain from the lumbar spine is the most frequent cause of posterior hip pain. Common lumbar issues like herniated discs and sciatic radiculopathy are often implicated. This pain referral is due to the lumbar plexus innervation of the hip, particularly via the L3 nerve root. Patients typically report worsening low back pain preceding the onset of posterior hip and/or buttock pain. Symptoms often reproduce with lumbar spine flexion or extension, and radicular symptoms may radiate down the leg. Treatment for referred pain targets the underlying lumbar pathology, ranging from conservative measures like therapy and activity modification to steroid injections or surgical intervention.

SI Joint Dysfunction: When the Pelvis is the Problem

SI joint dysfunction arises from various factors, including hypermobility, hypomobility, trauma, degenerative arthritis, inflammatory arthropathy (sacroiliitis), infection, ligament strain, and stress fractures. Patients may experience pain near the posterior superior iliac spine, with buttock pain radiating down the leg. Diagnosing SI joint pathology can be challenging, necessitating a thorough neurological exam to rule out other conditions like tumors. Imaging, including radiographs, CT scans, and MRIs (Figure 1), can be helpful. Fluoroscopic-guided SI joint injection, providing pain relief, is considered diagnostic. Treatment varies based on the cause, from physical therapy for strength/flexibility deficits to antirheumatic agents and NSAIDs for inflammatory conditions. Surgical correction, manipulation, and radiofrequency neurotomy are considered in refractory cases.

Figure 1. Sagittal MRI of Lumbosacral Spine Showing Herniated Nucleus Pulposus

Alt text: Sagittal view MRI of the lumbosacral spine revealing a substantial herniated nucleus pulposus at the L5-S1 level, depicted in both T2-weighted and proton density fat-saturated imaging sequences.

Extensor or Rotator Muscle Pain: Muscular Imbalances

The hip’s muscular support is complex, with numerous muscles in a confined space, often with overlapping functions. Strain or overuse in one muscle group can lead to generalized hip pain, complicating diagnosis. Hip extensor muscles, including the biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus, attach to the posterior pelvis. Strain or tears in these tendons can cause posterior hip pain. The biceps femoris has two proximal attachments: the long head to the ischial tuberosity and sacrotuberous ligament, and the short head to the linea aspera and lateral intermuscular septum. The semimembranosus and semitendinosus also originate from the ischial tuberosity. Injury to any hamstring tendon can result in posterior hip pain. Rotator muscles, both internal and external, also attach posteriorly; strain or overuse can cause posterior hip pain. Gluteal tendinopathy, while often causing lateral hip pain, should be considered. Treatment for muscle overuse is typically conservative: activity modification, physical therapy, and NSAIDs.

Piriformis Syndrome: Entrapment of the Sciatic Nerve

Piriformis syndrome is another significant cause of posterior hip pain, potentially accounting for up to 5% of low back, buttock, and leg pain cases. Patients typically experience sciatic nerve distribution pain: buttock pain radiating down the leg. Classic piriformis syndrome features include pain in the SI joint region, greater sciatic notch, and piriformis muscle, exacerbated by stooping or lifting, and potentially gluteal atrophy. Straight leg raise may be painful. The Pace test (pain with resisted hip abduction seated) and Freiberg test (pain with forceful hip internal rotation) can be positive. Pelvic or rectal examination might reveal a tender, palpable piriformis muscle mass. Diagnosis is often by exclusion due to vague clinical presentations and limited validated diagnostic tests. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies, if piriformis syndrome is suspected, may show sciatic nerve compression at the piriformis level. Traditional treatment involves conservative therapy, physical therapy, stretching, and steroid or analgesic injections. Botulinum toxin and arthroscopic release are emerging therapies showing promise.

Proximal Hamstring Rupture: A Tear in the Powerhouse

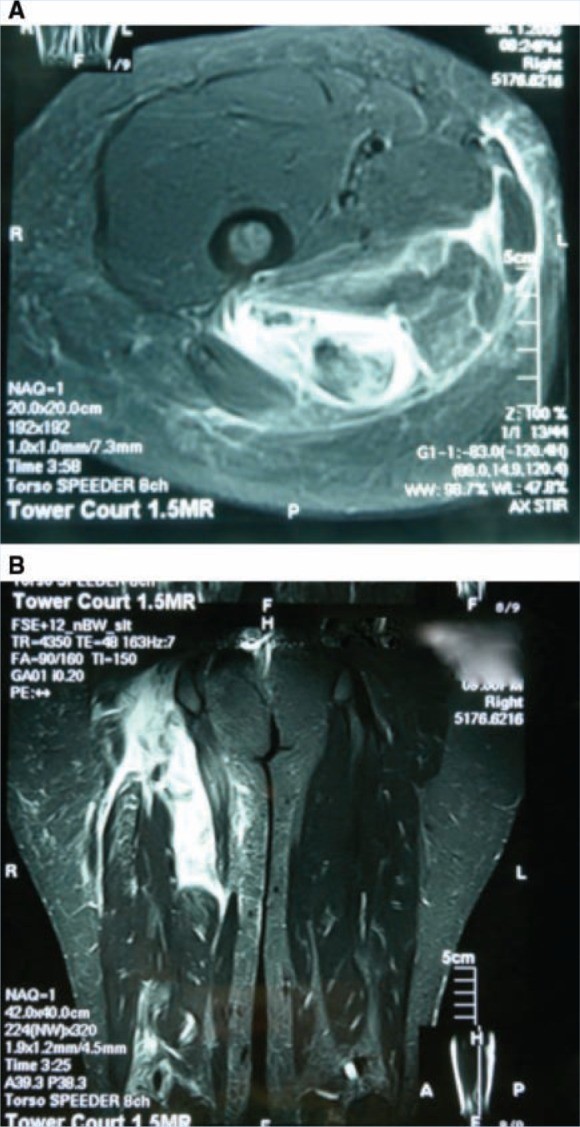

Proximal hamstring tendon rupture is a common cause of posterior hip pain. Injury can be acute, from a traumatic rupture, or chronic, from repeated hamstring strains and tendinitis. Patients present with posterior hip pain, muscle weakness, and sciatica signs. Historically, treatment was conservative, but recent research favors early surgical intervention over conservative treatment or delayed surgery for better outcomes. Surgical repair with allograft tendons has shown success in both acute and chronic cases (Figures 2-4).

Figure 2. Ecchymosis After Hamstring Tear

Alt text: Visual representation of ecchymosis, or bruising, observed during a physical examination, indicative of a torn hamstring muscle in the posterior thigh region.

Figure 3. MRI of Acutely Torn Hamstring Tendons

Alt text: T2-weighted MRI scans illustrating acutely torn hamstring tendons, with axial views showing tendon disruption and surrounding fluid, and coronal views displaying tendon retraction and hematoma formation.

Figure 4. Intraoperative Images of Proximal Hamstring Repair

Alt text: Intraoperative photographs capturing the surgical repair of a proximal hamstring rupture. Image A shows the proximal hamstring tendon end tagged with sutures, while Image B demonstrates the tendon repair to the ischium using suture anchors.

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI): A Less Common Posterior Cause

While FAI typically presents with groin pain, posterior hip pain presentations exist. FAI results from structural abnormalities causing chondral and labral injury with hip motion. Osseous abnormalities of the acetabulum and/or femoral head, including CAM and Pincer impingement, can lead to hip impingement (Figure 5). Athletes with recurrent groin strains unresponsive to physical therapy and resulting in range of motion loss may have FAI. These patients often have groin pain worsened by prolonged sitting or rotation. Physical exam reveals limitations in hip flexion, internal and external rotation. Less than 20° internal rotation is suspicious for FAI. The impingement sign (groin pain with flexion, adduction, internal rotation) is often positive. Posterior impingement test (hip extension and external rotation) can be positive in global acetabular overcoverage. Fluoroscopic hip injection with lidocaine can aid diagnosis; pain relief confirms intra-articular pain. MRI or CT scans further delineate hip morphology and cartilage/labrum injury. Surgery, open or arthroscopic, may be needed for refractory cases.

Figure 5. Bilateral Global Acetabular Overcoverage

Alt text: Radiographic image illustrating bilateral global acetabular overcoverage due to acetabular protrusio, with acetabular line medial to the ilioischial line and a visible crossover sign indicating anterior wall laterality.

Clinical Workup: A Systematic Approach

A systematic approach is crucial for diagnosing posterior hip pain and guiding treatment. For acute pain with low back pain or radiating symptoms, lumbar spine imaging is indicated to assess for herniated nucleus pulposus, degenerative disc disease, arthropathy, or spinal stenosis. Conservative treatment is typically the initial step. For gradual onset pain, common in overuse or sports-related injuries, physical examination helps narrow the differential. A positive FABER test or pelvic asymmetry suggests SI joint dysfunction, treated with physical therapy, activity modification, and injections. If symptoms persist, MRI or bone scan rules out pelvic stress reactions. Pain with resisted extensor/rotator muscle testing and gluteal tenderness points to muscle strain, treated with activity modification, physical therapy, and NSAIDs. Persistent groin strain with range of motion limitations may indicate FAI, requiring specialist referral and radiographic evaluation. Proximal hamstring avulsion necessitates immediate orthopedic referral for potential surgical repair.

Conclusions: Charting the Course to Relief

Posterior hip pain, while less common than other hip pain locations, presents diagnostic complexities. A structured, logical approach is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning. Common culprits behind posterior hip pain include referred pain from the lumbar spine, SI joint dysfunction, hip extensor or rotator muscle strain, proximal hamstring rupture, and piriformis syndrome. By systematically considering these diagnoses, clinicians can navigate the complexities of posterior hip pain and guide patients toward appropriate and effective management strategies.

Conflict of Interest: Shane J. Nho and Charles A Bush-Joseph report receiving research and institutional support from Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, Livatec, Miomed, Athletico, and DJ Ortho.

References (Same as original article)