Introduction

Diagnosing white lesions in the oral cavity, commonly manifesting as a white tongue, presents a considerable clinical challenge for healthcare professionals. These lesions encompass a broad spectrum of conditions, ranging from benign and transient to premalignant and malignant, each with distinct etiologies and prognoses. Accurate differential diagnosis is paramount to ensure timely and appropriate management, preventing delays in treatment, particularly for lesions with malignant potential. This article provides a comprehensive guide to the differential diagnosis of white tongue, employing a clinical decision tree approach to aid clinicians in navigating this complex diagnostic landscape.

Oral white lesions, while constituting a relatively small percentage of oral pathologies, carry significant clinical importance due to the malignant potential associated with certain conditions such as leukoplakia, lichen planus, and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. These lesions necessitate a systematic diagnostic approach to rule out malignancy and guide appropriate intervention.

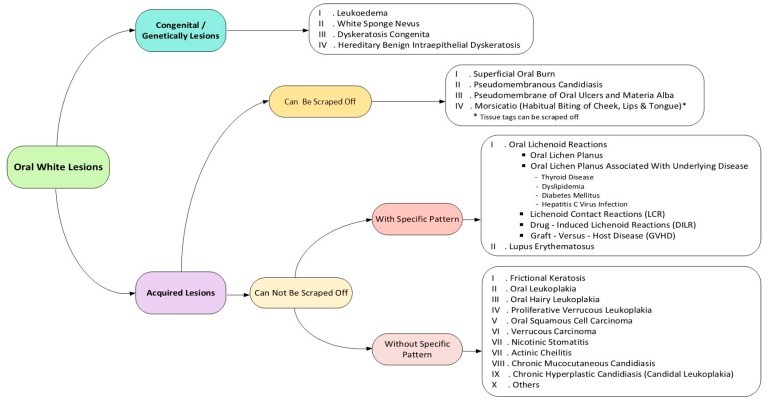

The development of white tongue and associated oral white lesions can be broadly categorized as congenital or acquired. Congenital lesions often present early in life and are typically long-lasting, whereas acquired lesions develop later due to various factors. The clinical appearance of white lesions stems from either a thickened keratin layer or the accumulation of non-keratinized material on the oral mucosa. A crucial initial step in diagnosis involves determining whether the white lesion can be scraped off. Scrapeable lesions often indicate superficial non-keratotic material, such as pseudomembranes commonly associated with fungal infections or chemical irritations. Conversely, non-scrapeable white lesions usually arise from an increased keratin layer thickness, potentially induced by local irritation, immunological responses, or more serious processes like premalignant or malignant transformation.

Further diagnostic refinement involves assessing the clinical pattern of the white lesion. Specific patterns, such as papular, annular, reticular, or erosive-ulcerative presentations, are characteristic of certain conditions, particularly lichenoid lesions, and aid in differentiating patterned from non-patterned white lesions.

This guide utilizes a three-step clinical approach to evaluating white tongue and oral white lesions: determining if the lesion is congenital or acquired, assessing its scrapeability, and identifying any specific clinical patterns. This diagnostic framework is presented as an updated clinical decision tree, designed to facilitate a logical and systematic approach to differential diagnosis, moving away from haphazard assessments towards rational clinical decision-making.

Search Strategy

The information presented in this guide is based on a comprehensive review of relevant literature. General search engines and specialized databases, including PubMed, PubMed Central, EBSCO, Science Direct, Scopus, and Embase, were utilized to identify pertinent articles and textbook chapters. Search terms included MeSH keywords such as “mouth disease,” “oral keratosis,” “oral leukokeratosis,” and “oral leukoplakia.” English-language articles published between 2000 and 2017, encompassing reviews, meta-analyses, original research papers (randomized and non-randomized clinical trials, cohort studies), case reports, and case series related to oral diseases, were evaluated for inclusion. This review focused on clinically relevant aspects of approximately 20 distinct entities associated with white tongue and oral white lesions, categorized by their nature of development (congenital or acquired) and clinical characteristics (scrapeable or non-scrapeable, patterned or non-patterned), as summarized in the decision tree (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Congenital/Genetic White Tongue Lesions

Congenital or genetically determined white lesions of the oral mucosa are typically present from birth or early childhood and often have a familial inheritance pattern. These lesions are generally non-scrapeable and lack specific patterns, requiring careful differentiation based on clinical features and patient history.

3.1. Leukoedema

Leukoedema is a common, benign variation of the oral mucosa, often observed as a diffuse, milky-white or gray-white, non-scrapeable appearance, particularly on the buccal mucosa. It is more prevalent in individuals with darker skin pigmentation and smokers, although the exact etiology remains unclear. A key diagnostic feature of leukoedema is its temporary disappearance upon stretching the mucosa (Figure 2). It is asymptomatic and requires no treatment.

Figure 2.

3.2. White Sponge Nevus

White sponge nevus (WSN) is a rare, inherited condition characterized by thickened, white, spongy plaques affecting the oral mucosa, most commonly the buccal mucosa bilaterally. Lesions typically appear in early childhood and are caused by genetic mutations affecting keratin production. WSN lesions are non-scrapeable, asymptomatic, and benign, requiring no treatment.

3.3. Dyskeratosis Congenita

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a rare, inherited bone marrow failure syndrome associated with oral leukoplakia, nail dystrophy, and abnormal skin pigmentation. Oral manifestations include bullae, erosions, and leukoplakic lesions, often progressing to premalignant leukoplakia with a significant risk of malignant transformation. Management focuses on symptom alleviation and monitoring for malignant changes.

3.4. Hereditary Benign Intraepithelial Dyskeratosis

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (HBID) is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder primarily affecting the conjunctiva and oral mucosa. Oral lesions resemble WSN, presenting as thick, white plaques, while ocular lesions manifest as gelatinous plaques on the conjunctiva. HBID is benign in the oral cavity, requiring treatment only for secondary candidal infections or symptomatic ocular involvement.

Acquired Scrapeable White Tongue Lesions

Acquired white lesions that can be scraped off typically indicate superficial deposits or pseudomembranes on the oral mucosa. These lesions are often associated with infections, trauma, or poor oral hygiene.

4.1. Superficial Oral Burn

Superficial oral burns, whether thermal or chemical, can result in a white, sloughy appearance of the oral mucosa. Thermal burns are commonly caused by hot foods or beverages, while chemical burns can arise from topical medications or caustic agents (Figure 3). These lesions are scrapeable and typically resolve spontaneously with symptomatic management, such as analgesics and antiseptic mouthwashes.

Figure 3.

4.2. Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

Pseudomembranous candidiasis, or oral thrush, is a common fungal infection characterized by creamy white plaques that can be easily scraped off, revealing an erythematous base (Figure 4). It is frequently observed in infants, the elderly, immunocompromised individuals, and those using broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antifungal medications are the mainstay of treatment.

Figure 4.

4.3. Pseudomembrane of Oral Ulcers and Materia Alba

Pseudomembranes can form over oral ulcers as a protective layer composed of fibrin and necrotic cells, appearing as a white or yellowish-white coating. Materia alba, accumulated oral debris due to poor hygiene, can also present as a scrapeable white coating on the tongue. Both are easily removed, revealing an underlying ulcerated or normal mucosa, respectively. Management involves addressing the underlying cause and improving oral hygiene.

4.4. Morsicatio

Morsicatio, or chronic cheek/lip biting, results in shaggy, thickened, gray-white patches on the buccal mucosa, lips, or lateral tongue borders (Figure 5). These lesions are scrapeable and caused by habitual self-inflicted trauma. Management focuses on behavior modification and eliminating the habit.

Figure 5.

Acquired Non-Scrapeable White Tongue Lesions with Specific Patterns

Acquired non-scrapeable white lesions with specific patterns often indicate underlying inflammatory or immune-mediated conditions. These lesions require careful clinical examination and may necessitate biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

5.1. Lichenoid Reactions

Lichenoid reactions encompass a group of lesions with similar clinical and histological features but diverse etiologies, including oral lichen planus, lichenoid contact reactions, drug-induced lichenoid reactions, and graft-versus-host disease. These lesions typically present with reticular, papular, plaque-like, or erosive-ulcerative patterns.

5.2. Oral Lichen Planus

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory condition of unknown etiology, commonly manifesting as reticular white striae (Wickham’s striae), papules, or plaques, often bilaterally on the buccal mucosa (Figure 6). Other forms include erythematous, bullous, and ulcerative variants. OLP is considered a potentially malignant disorder, requiring long-term monitoring. Management depends on the clinical form and symptom severity, often involving topical corticosteroids and antifungal agents.

Figure 6.

5.3. Oral Lichen Planus Associated with Underlying Diseases

OLP has been associated with several systemic conditions, including hepatitis C virus, dyslipidemia, thyroid disease, and diabetes mellitus. Clinicians should consider these associations in patients diagnosed with OLP.

5.4. Lichenoid Contact Reactions

Lichenoid contact reactions (LCRs) are hypersensitivity reactions to dental materials, such as amalgam or composite restorations, manifesting as lichen planus-like lesions adjacent to the offending material (Figure 7). Lesions typically resolve upon removal of the dental material.

Figure 7.

5.5. Drug-Induced Lichenoid Reactions

Drug-induced lichenoid reactions (DILRs) are adverse drug reactions mimicking OLP, caused by various medications. DILRs are often unilateral and may resolve upon drug withdrawal.

5.6. Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD)

Oral graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a complication of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, presenting with lichenoid lesions throughout the oral mucosa, often accompanied by skin and liver involvement.

5.7. Lupus Erythematosus

Oral lesions in lupus erythematosus (LE), both systemic (SLE) and chronic cutaneous (CCLE), can present with white striae radiating from erythematous areas, resembling OLP, or as ulcerations and plaques. Diagnosis requires correlation with systemic and cutaneous findings and often necessitates biopsy.

Acquired Non-Scrapeable White Tongue Lesions without Specific Patterns

Acquired non-scrapeable white lesions without specific patterns encompass a diverse group of conditions, including reactive, premalignant, and malignant lesions. These lesions often require biopsy for definitive diagnosis and risk assessment.

6.1. Frictional Keratosis

Frictional keratosis is a reactive white plaque caused by chronic mechanical irritation, such as cheek biting or rubbing against a sharp tooth. The lesion typically resolves upon removal of the irritant.

6.2. Oral Leukoplakia

Oral leukoplakia (OL) is a descriptive term for a white plaque that cannot be clinically or histopathologically diagnosed as any other specific lesion (Figure 8). OL is a potentially malignant disorder, with a variable risk of malignant transformation depending on clinical subtype and location. Management includes risk factor modification, close monitoring, and biopsy for dysplasia assessment.

Figure 8.

6.3. Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is a white, non-scrapeable, vertically corrugated lesion typically located on the lateral border of the tongue, associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with HIV/AIDS (Figure 9). OHL is not premalignant but serves as an indicator of immunosuppression.

Figure 9.

6.4. Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (PVL) is a high-risk, aggressive form of leukoplakia characterized by slow but relentless progression, multifocal involvement, and a high rate of malignant transformation, often to verrucous carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 10). PVL typically affects elderly women and requires aggressive management and lifelong monitoring.

Figure 10.

6.5. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common oral malignancy and can present as a white, red, or mixed red-and-white lesion, often with surface texture changes, ulceration, or induration (Figure 11). Early detection and diagnosis are crucial for improving survival rates.

Figure 11.

6.6. Verrucous Carcinoma

Verrucous carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally invasive, low-grade variant of OSCC, often associated with smokeless tobacco use. It presents as a thick, white, papillary or verruciform plaque.

6.7. Nicotinic Stomatitis

Nicotinic stomatitis, or smoker’s palate, is a white lesion on the hard palate with scattered red dots representing inflamed salivary gland ducts, caused by heat and chemicals from smoking (Figure 12). It is not premalignant and typically resolves upon smoking cessation.

Figure 12.

6.8. Actinic Cheilitis

Actinic cheilitis is a premalignant condition of the lower lip vermilion caused by chronic sun exposure, presenting with dryness, cracking, atrophy, and white keratotic plaques. It carries a risk of malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma.

6.9. Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) is a rare, persistent Candida infection affecting the skin, nails, and mucous membranes, including the oral mucosa. Oral lesions are typically white plaques that are difficult to scrape off.

6.10. Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis (Candidal Leukoplakia)

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (CHC) is a form of candidiasis presenting as non-scrapeable white plaques, often in the retrocommissural area. It is considered a type of leukoplakia with an association with Candida infection and a potentially increased risk of malignant transformation.

7. Other White Tongue Conditions

Less common causes of white tongue or oral pallor include submucous fibrosis, certain granulomatous diseases, skin grafts, scar tissue, and uremic stomatitis.

8. Discussion

The differential diagnosis of white tongue and oral white lesions is a complex process requiring careful clinical assessment and a systematic approach. The decision tree presented in this guide provides a structured framework for clinicians to navigate this diagnostic challenge.

Congenital non-scrapeable white lesions are typically identified early in life, often with a family history. Differentiating leukoedema, WSN, DC, and HBID relies on specific clinical features, such as lesion disappearance upon stretching in leukoedema, extraoral involvement in WSN and HBID, and associated systemic findings in DC.

Acquired scrapeable white lesions are often related to trauma or infection. Superficial burns, morsicatio, and pseudomembranes of ulcers are usually diagnosed based on history and clinical presentation. Pseudomembranous candidiasis is a common differential, particularly in susceptible populations.

Acquired non-scrapeable white lesions are further categorized by the presence or absence of specific patterns. Patterned lesions, primarily lichenoid reactions, share overlapping clinical features and require careful consideration of etiology, such as dental materials in LCR, medications in DILR, and transplant history in GVHD. Lupus erythematosus should also be considered in the differential of patterned white lesions.

Non-patterned, non-scrapeable white lesions represent a diverse group with varying malignant potential. Frictional keratosis is a reactive lesion related to trauma. Oral leukoplakia is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring careful risk assessment and monitoring. OHL is associated with immunosuppression. PVL and OSCC represent high-risk lesions requiring prompt diagnosis and management. Nicotinic stomatitis and actinic cheilitis are associated with specific habits and exposures. CHC is linked to Candida infection and may carry an increased malignant risk.

9. Conclusion

White tongue and oral white lesions represent a diagnostic challenge necessitating a systematic and stepwise approach. This guide provides an updated clinical decision tree to aid clinicians in differential diagnosis, facilitating timely and appropriate management of these diverse conditions. Accurate diagnosis is critical for preventing delays in treatment and ensuring optimal patient outcomes, particularly for lesions with malignant potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.; methodology, H.M.; data collection, H.M., M.B., S.J; writing—original draft preparation, S.J., F.A., S.R., Y.S.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and F.A.; visualization, and supervision, H.M., and M.B.; project administration, H.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.