Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition affecting millions worldwide, and recent years have shown a notable increase in the number of diagnoses. This surge has sparked considerable discussion and debate, raising critical questions about the factors driving this trend. Are we facing an overdiagnosis epidemic, fueled by the over-prescription of stimulant medications? Or are we finally recognizing and addressing previously undiagnosed cases, particularly within underrepresented populations?

This article delves into the complex issue of rising ADHD diagnosis rates, exploring the historical evolution of the disorder, changes in diagnostic criteria, and the growing awareness among both healthcare professionals and the public. By examining these different facets, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of why ADHD diagnoses are on the rise and what this means for individuals and communities.

ADHD: Understanding the Fundamentals

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is characterized as a neurodevelopmental disorder with a global impact, affecting an estimated 5% to 7.2% of young individuals and 2.5% to 6.7% of adults. In the United States, recent data suggests an even higher prevalence among children, reaching approximately 8.7%, or 5.3 million individuals. While historically considered a childhood condition, it is now recognized that ADHD symptoms persist into adulthood for up to 90% of those diagnosed in childhood. Furthermore, a significant number of adults with ADHD, as high as 75% in one study, were not diagnosed during their childhood years. Interestingly, the gender ratio shifts with age: while boys are diagnosed more frequently than girls in childhood (4:1), this ratio becomes nearly equal (1:1) in adulthood.

The etiology of ADHD is believed to be multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental influences. Twin studies have highlighted a strong hereditary component, estimating heritability at 60–70%, and research has identified several genes potentially linked to ADHD vulnerability. These genes include those regulating Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor, crucial for learning and memory, and those involved in the brain’s dopamine system modulation. Environmental factors, such as perinatal complications and exposure to toxins, are also considered contributing risks.

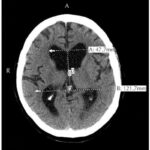

Diagnosis of ADHD is primarily clinical, relying on a combination of questionnaires, clinical interviews, and, in some cases, neuropsychiatric testing. Although neuroimaging studies have indicated potential links between ADHD and white matter volume abnormalities in specific brain pathways, current biomarkers are not sufficiently sensitive for diagnostic use.

Treatment strategies for ADHD typically involve a multimodal approach, integrating medication, skill-building techniques, and psychotherapy. The serendipitous discovery in the 1930s by Dr. Charles Bradley, who observed improved behavior and academic performance in children treated with amphetamine sulfate, marked the beginning of stimulant medication use for ADHD. Stimulants remain the first-line and gold-standard pharmacological treatment, demonstrating effectiveness in up to 70% of cases. However, it’s important to acknowledge the potential side effects, such as decreased appetite, anxiety, nausea, and headaches, as well as concerns about tolerance, weight loss, and insomnia, particularly in children. Long-term stimulant use continues to be studied, with recent reviews suggesting general safety but advising caution in prescribing to very young children, adolescents at high risk of substance abuse, and individuals with tics or psychosis.

Beyond medication, various non-pharmacological treatments are available, including behavioral parent training, mindfulness-based attention training, and psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Neurofeedback, a newer approach, shows promise but requires further research to establish its efficacy and practical clinical application.

ADHD Google Search Trends from 2004 to present

ADHD Google Search Trends from 2004 to present

The Shifting Sands: Evolution of ADHD Diagnostic Criteria

To understand the increasing diagnosis rates, it’s crucial to trace the historical evolution of ADHD and its diagnostic criteria. Early descriptions of attention-related disorders date back to the 18th century when Sir Alexander Crichton, in his 1798 book On Attention and its Diseases, described “morbid alterations” of attention hindering individuals’ ability to focus on education.

In the early 20th century, Sir George Frederic Still, a British physician, described children with a “defect of moral control,” characterized by impulsivity and poor frustration tolerance, traits now recognized as ADHD features, although his description also overlaps with conduct and oppositional disorders. Later, in the 1930s, Kramer and Pollnow described “hyperkinetic disease of infancy,” a syndrome closely resembling modern ADHD, encompassing hyperactivity, emotional excitability, impulsivity, and inattention.

ADHD officially entered the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1968 as “Hyperkinetic Reaction of Childhood,” emphasizing hyperactivity and distractibility. Subsequent DSM editions marked a significant shift towards attention deficit as the core feature. The DSM-III in 1980 introduced “attention deficit disorder,” or ADD, a term still commonly used, and established specific criteria including symptom count, age of onset, symptom duration, and exclusion of other psychiatric disorders and substance use.

The term ADHD as we know it today emerged in 1987 with the DSM-III-R, combining inattention and hyperactivity into a single diagnosis. The DSM-IV further refined the diagnosis, categorizing it into three subtypes: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined type. The DSM-5, released in 2013, broadened the definition of ADHD significantly. Key changes are summarized in the table below. Notably, the DSM-5 allowed for co-diagnosis of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which was previously not permitted. This change, along with others, undoubtedly contributed to the increased ADHD prevalence by including a substantial group previously excluded.

Table 1. Changes in ADHD Diagnostic Criteria: DSM-IV vs. DSM-V

| DSM-IV | DSM-V |

|---|---|

| Number of symptoms required | 6 or more in either inattention or hyperactivity domains |

| Age of symptom onset | Symptoms causing impairment before age 7 |

| Impairments at onset | Onset of impairment required |

| Pervasiveness | “Evidence of impairment in 2 or more settings” |

| Autism exclusionary? | Yes |

The evolution of diagnostic criteria undeniably accounts for a portion of the rise in ADHD diagnoses. Epidemiological research has consistently shown that variations in prevalence rates across studies are often linked to differences in diagnostic measurement, particularly the criteria used and the inclusion or exclusion of functional impairment.

However, these evolving criteria also complicate clinical diagnosis. In the absence of definitive biomarkers, diagnosis relies on subjective signs and symptoms. Clinicians utilize screening questions (examples in Table 2) to aid assessment, but this inherent subjectivity can lead to both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis. The overlapping nature of psychiatric symptoms further complicates matters, often resulting in missed ADHD diagnoses and inaccurate psychiatric labels. This is particularly concerning given ADHD’s high comorbidity rates with other conditions like behavioral disorders (52%), anxiety (33%), depression (17%), and autism (14%). While comorbidity might contribute to overdiagnosis in some cases, it more frequently leads to ADHD being misdiagnosed and inadequately treated. Adult ADHD self-report scales (ASRS) and reports from schools and family members are valuable tools in assessment. Neuropsychiatric testing is also an option, though not mandatory for diagnosis.

Table 2. Sample Questions for ADHD Assessment by Clinicians

| Helpful Diagnostic Questions for Clinicians |

|---|

| Could you describe how it feels when you have to sit through a long movie or meeting? |

| Tell me how you did with being attentive in class in middle school compared to other students? |

| What is your experience when you try to read or focus on work for an extended period of time? |

| Have you ever made a mistake on an exam or at work that could have easily been prevented? |

| Do you often lose things like your keys or cell phone? If so, what do you do to keep track of them? |

| How likely are you to remember to do a task without writing it down (make a phone call, water the plants, do the laundry etc..) |

| What happens when you have a lot of tasks to do and need to get them all done? |

| Tell me about your ability to focus on things you like and want to do as opposed to harder less exciting things. |

| Do your friends and family ever ask you if you are paying attention to them? Do you feel you need to ask them to repeat something? Do you sometimes pretend you heard the conversation but actually didn’t? |

| Do you ever feel the urge to say whatever is on your mind right there and then, sometimes interrupt people? Does it ever get you in trouble with others? For example, losing friendships, or having difficulties with your boss? |

| Do you drink coffee? If so, how much and how do you notice it affects you? |

The Power of Awareness: How Knowledge Fuels Prevalence

Beyond diagnostic criteria changes, increased awareness among physicians and the general public is a significant factor contributing to rising ADHD diagnoses. This heightened awareness is driven by multiple factors, including dedicated awareness campaigns, improved access to healthcare, and cultural shifts. Notably, October has been designated ADHD Awareness Month since 2004. Google Trends data illustrates this growing public interest, showing a consistent increase in ADHD-related searches, peaking in March 2022.

ADHD has also permeated popular culture. Characters exhibiting ADHD traits have appeared in literature for centuries, such as “Fidgety Philip” and “Johnny Look-in-the-Air” in Heinrich Hoffman’s mid-1800s stories. Today, numerous movie and television characters, like Barney Stinson from “How I Met Your Mother” and Phil Dunphy from “Modern Family,” incorporate ADHD-like traits into their personalities and storylines. Social media platforms, particularly TikTok and Twitter, have further amplified ADHD awareness. The hashtag #adhd on TikTok has garnered billions of views, with many individuals crediting these platforms for helping them recognize their symptoms and seek diagnosis and treatment. However, the accessibility of information on the internet also comes with the risk of misinformation. Studies indicate that a significant portion of ADHD content on TikTok is misleading, particularly content from non-healthcare providers. Conversely, content from healthcare professionals is generally found to be accurate and beneficial.

The Shadow of Undertreatment: Addressing the Missed Cases

While concerns about rising ADHD diagnoses often center on potential overdiagnosis, it’s crucial to recognize the significant issue of undertreatment. A U.S. national survey in 2006 revealed that only 11% of adults with ADHD were receiving treatment. Untreated ADHD can have profound consequences, impacting education, career, and finances, leading to higher dropout rates, unemployment, and lower income. Interpersonal relationships also suffer, with higher rates of divorce reported among adults with ADHD. Furthermore, untreated ADHD elevates the risk of substance abuse, car accidents, injuries, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. The implications of underdiagnosis extend far beyond mere difficulty focusing.

Concerns about non-medical stimulant use, particularly among students seeking cognitive enhancement or recreational use, are often raised. However, studies suggest that non-prescribed stimulant use, while present, often occurs among students already struggling with attentional difficulties, potentially indicating undiagnosed ADHD rather than purely performance enhancement motives. Importantly, recent research suggests that pharmacological treatment of ADHD is associated with a decrease in substance use risk, not an increase.

Unmasking Disparities: ADHD in Minoritized Populations

A comprehensive understanding of ADHD diagnostic trends necessitates examining disparities among minoritized populations. Increased awareness of these disparities may also contribute to rising diagnosis rates as previously overlooked groups are increasingly identified. For two decades, research has highlighted persistent disparities in ADHD diagnosis related to race and gender. For instance, in the mid-2000s, Black students were more likely to exhibit ADHD symptoms than White students, but less likely to receive a diagnosis. However, in the following decade, diagnosis rates among Black individuals increased at a faster pace than among White individuals. Similar trends are observed among girls, whose diagnosis rates have risen more rapidly than boys’ rates over the past two decades. Experts suggest that changes in DSM-IV criteria, emphasizing inattention over hyperactivity, contributed to the increased diagnoses in females, who often present with predominantly inattentive symptoms. Between 1991 and 2008, diagnosis rates in girls increased significantly more than in boys. This suggests that greater awareness of previously missed presentations of ADHD, particularly in girls and underrepresented groups, is leading to more accurate diagnoses.

Despite these positive trends, data indicates that ADHD continues to be underdiagnosed in BIPOC youth and females compared to their White male counterparts, even after accounting for socioeconomic factors and adverse childhood experiences. Girls are often diagnosed at older ages and report higher stress levels. These disparities stem from systemic factors, including racial and gender bias. Diagnosis relies on subjective interpretation of behaviors and clinician integration of reports from various sources. Studies have found that clinicians may be more responsive to White parents seeking ADHD diagnosis and treatment compared to BIPOC parents. Furthermore, BIPOC youth with ADHD are disproportionately misdiagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder (CD).

Gender also plays a role in symptom presentation and recognition. Social expectations may lead girls to internalize hyperactivity, while boys are more likely to exhibit externalizing behaviors, leading to earlier detection. Historically, boys have been more likely to be diagnosed due to hyperactivity, while girls, often presenting with inattentive symptoms, were overlooked. Interestingly, some research suggests that there may not be a true difference in hyperactivity levels between genders, but rather a bias among teachers leading to under-recognition of hyperactive symptoms in girls. Focusing solely on “overdiagnosis” concerns may be detrimental, particularly for these underdiagnosed populations, creating further barriers to accessing appropriate care.

Conclusion: Navigating the Landscape of Rising ADHD Diagnoses

The increasing prevalence of ADHD diagnoses is a multifaceted phenomenon, influenced by evolving diagnostic criteria, growing public and professional awareness, and improved identification of previously underdiagnosed groups, particularly women and minorities. Media and social media have played a significant role in raising public awareness, prompting individuals to seek professional evaluations. While concerns about overdiagnosis and stimulant misuse exist, evidence suggests that these factors have a limited impact on overall diagnostic trends. Instead, focusing on “overdiagnosis” may be harmful, especially for populations who have historically been missed by the diagnostic process, creating additional obstacles to care and reinforcing stigma. A holistic, patient-centered approach is crucial, balancing the risks of both treatment and undertreatment. For individuals struggling with unrecognized ADHD, accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment can be transformative, improving mental health, social functioning, and overall quality of life.

References

References from the original article should be listed here. (Since the original article provides numbered in-text citations and a reference list implicitly, I will assume the user has access to these and can re-insert them here if needed for the final output).