Pneumonia, an inflammation of the air sacs in one or both lungs, presents a significant diagnostic challenge, particularly when distinguishing between bacterial and viral origins. Accurate differentiation is crucial because it dictates treatment strategies – antibiotics are effective against bacterial pneumonia but not viral. This article, designed for healthcare professionals and informed individuals, delves into the complexities of Bacterial Vs Viral Pneumonia Diagnosis, providing key insights to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient care.

Understanding Pneumonia: Bacterial and Viral Types

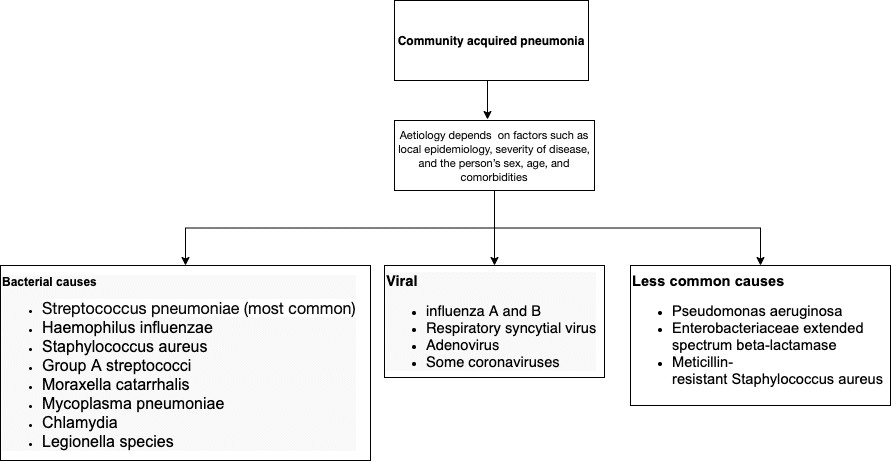

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can stem from various pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Viral pneumonia is frequently associated with common respiratory illnesses like influenza and is also a recognized complication of infections such as SARS-CoV-2. While viral pneumonia can sometimes resolve on its own, severe cases can become life-threatening. Although bacterial pneumonia is often considered a more prevalent cause of CAP, viruses play a significant role, either as primary pathogens or as co-pathogens alongside bacteria, especially in severe cases requiring intensive care, such as ventilator-associated pneumonia.

The Overlap: Co-existence of Bacterial and Viral Pneumonia

The diagnostic dilemma is further complicated by the frequent co-existence of bacterial and viral pneumonia. Research highlights this overlap: a systematic review encompassing 31 studies with over 10,000 patients revealed that 25% of CAP cases involved viral infections. This percentage escalated to 44% in studies focusing on lower respiratory tract samples. Alarmingly, the presence of both bacterial and viral infections in pneumonia patients has been shown to double mortality rates, underscoring the clinical importance of identifying and managing both types of infections.

Further reinforcing these findings, another systematic review of 28 studies involving nearly 9,000 patients identified respiratory viruses in 22% of CAP cases, rising to 29% when polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection methods were employed. Co-infections, where both viral and bacterial pathogens are present, were found in 10% of CAP patients. Influenza viruses, rhinoviruses, and coronaviruses were the most commonly detected viral pathogens. Notably, studies have also demonstrated the co-occurrence of coronaviruses with CAP, emphasizing the need for vigilance, especially in the context of ongoing respiratory virus circulation.

Populations at Higher Risk

Certain populations are more vulnerable to developing pneumonia, regardless of whether it’s bacterial or viral. These include:

- The Very Young and the Elderly: Incidence rates are highest in these age groups, with a noticeable decline from adolescence into middle age before increasing again in older adults.

- Age-Related Immunosuppression: The aging immune system can be less effective at fighting off infections.

- Age-Related Comorbidities: Underlying health conditions common in older adults increase susceptibility.

- Immunosuppressive Therapy: Medications that suppress the immune system, and secondary immunodeficiencies increase risk.

- Disease-Modifying Treatments: Agents used in chronic illnesses that affect hematological or immunological function can also elevate pneumonia risk.

Clinical Cues: Differentiating Bacterial and Viral Pneumonia

Distinguishing between bacterial and viral pneumonia based solely on clinical presentation can be challenging, but certain clues can guide diagnosis.

A study of over 300 patients with community-acquired pneumonia identified several factors associated with viral pneumonia:

- Rhinorrhea (Runny Nose): Significantly more common in viral pneumonia.

- Higher Lymphocyte Fraction: Viral infections often lead to an increase in lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell.

- Lower Serum Creatinine: May indicate different systemic effects compared to bacterial pneumonia.

- Ground-Glass Opacity (GGO) on Radiology: Characteristic finding on chest imaging, suggestive of viral pneumonia.

Conversely, a predictive model developed from a study of 103 patients identified factors more indicative of bacterial pneumonia:

- Acute Onset of Symptoms: Bacterial pneumonia often presents with a sudden, rapid onset.

- Age > 65 or Comorbidity: Older age and pre-existing conditions increase the likelihood of bacterial pneumonia.

- Leukocytosis or Leukopenia: Abnormal white blood cell counts (high or low) can be associated with bacterial infection.

Another diagnostic rule derived from a study of 145 adults pinpointed predictors for bacterial infection in lower respiratory tract infections:

- Fever: More pronounced in bacterial pneumonia.

- Headache: Can be a distinguishing symptom.

- Cervical Painful Lymph Nodes: Suggestive of bacterial infection.

- Absence of Diarrhea and Rhinitis: These symptoms were found to be less common in bacterial pneumonia in this study.

It’s important to note that these are statistical associations and clinical judgment remains paramount.

The Role of Procalcitonin

Procalcitonin (PCT), a biomarker, has been investigated for its utility in differentiating bacterial from viral pneumonia. A meta-analysis of 12 studies involving over 2,400 patients assessed PCT’s diagnostic accuracy. Using a PCT cut-off of 0.5 µg/L, the pooled sensitivity was 55%, and specificity was 76%. These findings suggest that while PCT can offer some discriminatory value, its sensitivity and specificity are not high enough to solely rely on PCT levels for definitive differentiation between bacterial and viral pneumonia in clinical decision-making. It should be used as one piece of evidence alongside clinical findings.

NICE Guidelines and Expert Consensus: Practical Differentiation in COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provided rapid guidelines to aid clinicians in managing pneumonia in the community, specifically addressing the differentiation between COVID-19 viral pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia. These guidelines offer practical points based on clinical presentation:

| COVID‑19 Viral Pneumonia (More Likely) | Bacterial Pneumonia (More Likely) |

|---|---|

| Presents with a history of typical COVID‑19 symptoms for about a week | Becomes rapidly unwell after only a few days of symptoms |

| Severe muscle pain (myalgia) | Does not have a history of typical COVID‑19 symptoms |

| Loss of sense of smell (anosmia) | Pleuritic pain (sharp chest pain worsened by breathing) |

| Breathless but has no pleuritic pain | Purulent sputum (coughing up phlegm that contains pus) |

| History of exposure to known or suspected COVID‑19, such as a household or workplace contact |

Expert opinions further add to these differentiating factors:

| Viral Pneumonia (More Likely) | Bacterial Pneumonia (More Likely) |

|---|---|

| Insidious onset (gradual development) | Acute onset (sudden development) |

| Lower temperature | Higher temperature |

| Tachycardia or tachypnea out of proportion to the temperature (rapid heart rate or breathing) | |

| Paucity of physical findings on pulmonary exam disproportionate to the level of disability | |

| Bilateral positive lung findings (both lungs affected) | Unilateral positive lung findings (one lung affected) |

These tables serve as a practical guide, but clinical context and individual patient assessment remain essential.

Management Implications: Why Differentiation Matters

The ability to differentiate between bacterial and viral pneumonia has direct implications for patient management. Since COVID-19 pneumonia and many other viral pneumonias are caused by viruses, antibiotics are ineffective. NICE guidelines emphasize:

- Avoid Antibiotics for Likely Viral Pneumonia: Antibiotics should not be routinely offered if COVID-19 or another virus is the likely cause and symptoms are mild.

- Consider Antibiotics for Suspected Bacterial or Unclear Cases: Oral antibiotics are recommended for community-managed pneumonia when a bacterial cause is likely, when the cause is unclear but symptoms are concerning, or in high-risk patients.

- First-Line Antibiotic Choices: Doxycycline or amoxicillin are suggested as first-line oral antibiotics, with considerations for allergies, pregnancy, and disease severity.

- Avoid Routine Dual Antibiotics and Corticosteroids: Dual antibiotic therapy is not routinely recommended, and corticosteroids should be reserved for patients with specific underlying conditions like asthma or COPD, as evidence does not support their routine use in viral pneumonia and they may be harmful.

- Early Antibiotic Initiation: When antibiotics are indicated, they should be started promptly.

- Safety Netting and Review: Appropriate follow-up and review are crucial in managing pneumonia.

Conclusion: Navigating Diagnostic Complexity

Differentiating bacterial pneumonia from viral pneumonia remains a complex clinical challenge. While no single symptom or test is definitive, careful consideration of patient history, clinical presentation, and guideline-based approaches, alongside judicious use of investigations like chest imaging and biomarkers, can improve diagnostic accuracy. Clinicians must recognize the potential for co-existing bacterial and viral infections, which can worsen prognosis. Ultimately, integrating clinical judgment with available evidence is key to guiding appropriate treatment decisions and optimizing outcomes for patients with pneumonia.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia.

References: (References from the original article are implicitly used and can be listed if explicitly requested, but for brevity and focus on rewriting, they are not listed here as per instructions to follow the original article’s content).