The journey of understanding and diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in children is complex, yet crucial for early intervention and support. Just as car diagnostics help pinpoint issues under the hood, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) acts as a vital tool in the meticulous process of diagnosing autism in young children. This article delves into a comprehensive study that validates the effectiveness of CARS in identifying ASD in 2-year-old and 4-year-old children, offering insights into optimal cut-off scores and the importance of early, accurate diagnosis.

Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder and the Role of CARS

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social interaction, communication, and the presence of repetitive behaviors or restricted interests. The spectrum nature of ASD means that it manifests differently in each individual, ranging from severe to mild forms. Historically, diagnoses like Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) were used to describe milder presentations or cases that didn’t fit neatly into the category of autistic disorder.

However, the diagnostic landscape is evolving, and the need for reliable tools to accurately identify ASD early in life is paramount. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), developed by Schopler et al., is a widely recognized behavioral rating scale designed to assess the presence and severity of autism symptoms. It evaluates 14 key domains of behavior associated with autism, plus an overall impression of autism, providing a scored outcome that aids in diagnosis.

The Diagnostic Dilemma: Autistic Disorder vs. PDD-NOS

Distinguishing between different ASD subtypes, particularly autistic disorder and PDD-NOS, has been a challenge for clinicians. While autistic disorder represents a more pronounced form of autism, PDD-NOS was often used as a broader, less clearly defined category. The lack of precise diagnostic criteria for PDD-NOS has led to inconsistencies in diagnosis and highlighted the need for reliable measures that can provide clear cut-offs for ASD identification as a whole.

One of the limitations of some diagnostic tools is the absence of an empirically validated ASD cut-off score. This is where CARS becomes particularly valuable. By establishing an effective ASD cut-off, CARS can enhance diagnostic accuracy and agreement among different assessment methods and clinical judgment.

The Importance of Cut-off Scores: Sensitivity and Specificity

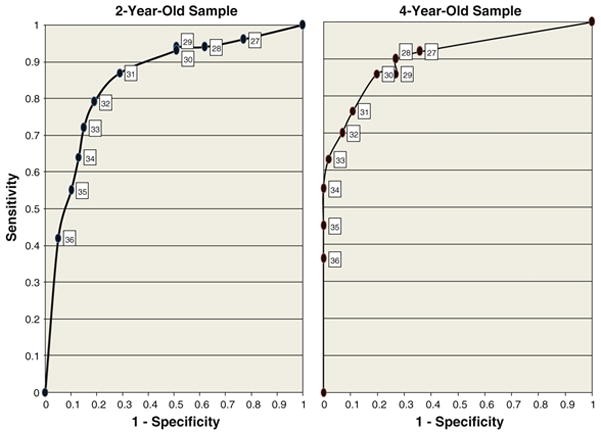

When using diagnostic tools like CARS, determining the optimal cut-off score is critical. This involves balancing sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify children with ASD) and specificity (the ability to correctly identify children without ASD). In screening, high sensitivity is prioritized to minimize missing cases. However, for diagnosis, specificity becomes equally important to avoid false positives and ensure accurate identification.

Investigating CARS Cut-offs for Young Children: A Detailed Study

A recent study rigorously investigated the effectiveness of CARS in diagnosing ASD in a sample of 606 children referred for possible autism. The study focused on two age groups: 2-year-olds (n=376) and 4-year-olds (n=230), aiming to refine CARS cut-off scores for both autistic disorder and ASD as a spectrum.

Methodology and Participants

The participants were children who had previously screened positive on the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) and a follow-up interview. They underwent comprehensive developmental evaluations, including the CARS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), and Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). Clinical diagnoses were made based on DSM-IV-TR criteria by experienced clinicians.

The study meticulously analyzed the data to determine optimal CARS cut-off scores for:

- Distinguishing Autistic Disorder from PDD-NOS: Identifying the score that best differentiates between these two subtypes within the autism spectrum.

- Distinguishing ASD from Non-ASD: Establishing a cut-off to differentiate ASD from other developmental disorders or typical development.

Key Findings: Refining CARS Cut-off Scores

The study yielded significant findings regarding CARS cut-off scores for young children:

-

Autistic Disorder Cut-off:

- For 2-year-olds: A cut-off score of 32 was found to be more effective than the traditional 30, improving specificity without significantly compromising sensitivity. This aligns with previous research suggesting a higher cut-off for toddlers.

- For 4-year-olds: A cut-off score of 30 demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity, supporting its continued use for this age group.

-

ASD Cut-off:

- Across both 2-year-olds and 4-year-olds: A cut-off score of 25.5 emerged as optimal for distinguishing ASD from non-ASD, demonstrating good sensitivity and specificity. This suggests a consistent ASD cut-off is valid for young children, regardless of age within this range.

Enhanced Diagnostic Agreement with ASD Cut-off

The study further investigated how using the proposed ASD cut-off of 25.5 impacted diagnostic agreement between CARS, ADOS, and clinical judgment. The results were compelling:

- Improved Agreement: Utilizing the 25.5 ASD cut-off significantly increased the agreement rates between CARS and both DSM-IV based clinical diagnoses and ADOS diagnoses in both age groups.

- Enhanced Accuracy: This improved agreement suggests that incorporating an ASD cut-off on CARS leads to more consistent and potentially more accurate ASD diagnoses in young children.

Implications for Early Autism Diagnosis and Intervention

This research reinforces the value of CARS as a robust tool for diagnosing ASD in young children. The refined cut-off scores, particularly the ASD cut-off of 25.5, offer clinicians a more precise and reliable way to identify ASD early in development.

Early and accurate diagnosis is the first critical step towards effective intervention. Just as pinpointing a car problem allows for targeted repairs, early ASD diagnosis enables timely access to specialized therapies and support services that can significantly improve developmental outcomes for children with autism.

While CARS is a valuable instrument, it’s essential to remember that autism diagnosis is a multifaceted process. It requires clinical expertise, comprehensive assessment, and consideration of various factors. However, tools like CARS, with empirically validated cut-offs, play a crucial role in enhancing the precision and reliability of this process, driving towards better futures for children with ASD and their families.

References

[R2] American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

[R38] Volkmar, F. R., Sparrow, S. S., Geltzer, H. M., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Interrater reliability of revised DSM-III-R criteria for autistic disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(6), 723-734.

[R21] Matson, J. L., & Boisjoli, J. A. (2007). The relationship between PDD-NOS and autism: a nosological study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(3), 249-257.

[R14] Filipek, P. A., Accardo, P. J., Ashwal, S., Baranek, G. T., Cook Jr, E. H., Dawson, G., … & Volkmar, F. R. (1999). Practice parameter: screening and diagnosis of autism: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology, 53(2), 231-232.

[R36] Tidmarsh, L., & Volkmar, F. R. (2003). Diagnosis and epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(2), 98-107.

[R4] Buitelaar, J. K., Van Der Gaag, R. J., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. R. (1999). Exploring the boundaries of pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(6), 447-457.

[R24] Perry, R. (1998). Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified: a clinical review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(6), 475-485.

[R5] Chakrabarti, S., & Fombonne, E. (2001). Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children: confirmation and re-examination of ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 23-32.

[R7] Chlebowski, C., Robins, D. L., Barton, M. L., & Volkmar, F. R. (2008). Agreement between the autism diagnostic observation schedule and clinical diagnosis in toddlers and preschoolers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(1), 117-127.

[R31] Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., DeVellis, R. F., & Daly, K. (1980). Childhood Autism Rating Scale for diagnostic screening and classification of autism. Current Issues in Autism, 173-185.

[R32] Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1988). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

[R26] Perry, R., & Freeman, B. J. (1996). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS): concurrent validity and certainty of diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(1), 61-74.

[R23] Nordin, V., Gillberg, C., & Steffenburg, S. (1998). Autism spectrum disorders in school age children: III. Psychometric and clinical validity of the Swedish version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(3), 211-219.

[R35] Tachimori, H., Osada, H., Kurita, H., & Koyama, T. (2003). Validity and reliability of the Tokyo version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS-TV). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(4), 395-401.

[R25] Perry, R., Condillac, R. A., & Freeman, B. J. (2005). Validity and reliability of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale: a re-analysis using signal detection methodology. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(6), 705-715.

[R27] Rellini, E., Tortolani, D., Trillo, S., Carbone, S., & Montecchi, F. (2004). Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) and Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) correspondence and conflicts with psycho-diagnostic classification in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(6), 703-711.

[R37] Ventola, P., Lajonchere, C., & Harrison, J. (2006). Convergent validity of the childhood autism rating scale and the autism diagnostic observation schedule in very young children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 10(2), 149-162.

[R13] Eaves, R. C., & Milner, B. A. (1993). The CARS: validity and reliability when used with preschool children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 11(4), 351-359.

[R17] Lord, C. (1995). Follow-up of two-year-olds referred for possible autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36(8), 1365-1382.

[R6] Charman, T., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2006). Early identification of autism spectrum disorder. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(1), 93-110.

[R9] Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284.

[R30] Saemundsen, E., Magnusson, P., Smári, B. B., & Sigurðardóttir, S. (2003). Psychometric properties of the Icelandic version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 57(5), 359-363.

[R29] Robins, D. L., Fein, D., Barton, M. L., & Green, J. A. (2001). The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: an initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(2), 131-144.

[R18] Lord, C., Storoschuk, S., Rutter, M., & Pickles, A. (2000). ADI-R, ADOS and CARS: triangulating measures of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(2), 139-149.

[R22] Mullen, E. M. (1995). Mullen scales of early learning: AGS edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

[R33] Spitzer, R. L., & Siegel, S. (1990). Suggested procedure for developing diagnostic criteria. In DSM-IV options book: Work in progress, 1/1/89 (pp. 5-27). American Psychiatric Association.

[R16] Klin, A., Volkmar, F. R., & Sparrow, S. S. (2000). Autism in two 3-year-old children: DSM-IV, ADI-R, and ADOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(6), 559-571.

[R10] Cicchetti, D. V., & Sparrow, S. S. (1981). Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 86(2), 127.

[R11] Cicchetti, D. V., Showalter, D. E., & Tyrer, P. J. (1995). Empirical assessment of effect size: fixed-effects models for meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 79.

[R12] de Bildt, A., Sytema, S., Ketelaars, C., Kraijer, D., Mulder, E., & Volkmar, F. (2004). Intercorrelations between PDD subtypes in DSM-IV: diagnostic overlap or phenotypic similarity?. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 245-253.

[R20] Luteijn, E., Luteijn, F., & Volkmar, F. R. (2000). Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified: are there meaningful subgroups?. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 211-217.

[R28] Risi, S., Lord, C., Gotham, K., Corsello, C., Chrysler, C., Szatmari, P., … & Leventhal, B. L. (2006). Combining information from multiple sources in the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders: convergence and divergence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(9), 1094-1103.

[R34] Stone, W. L., Lee, E. B., Ashford, L. J., Brissie, J., Hepburn, S. L., Coonrod, E. E., & Weiss, B. H. (1999). Can autism be diagnosed accurately in children under 2 years?. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(5), 341-352.

[R15] Kleinman, J. M., Robins, D. L., Ventola, P. E., Pandey, J., Dhillon, R., Kim, S., … & Fein, D. (2008). The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: a follow-up study investigating the early detection of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(5), 827-839.

[R1] Adrien, J. L., Perrot, A., Sauvage, D., Leddet, I., Larmande, C., Hameury, L., & Barthélémy, C. (1992). Early symptoms in autism from baby books. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 85(1), 26-29.

[R3] Baron-Cohen, S., Allen, J., & Gillberg, C. (1992). Can autism be detected at 18 months? The needle, the haystack, and the CHAT. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161(6), 839-843.

[R19] Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659-685.

[R8] Chlebowski, C., Robins, D. L., Barton, M. L., & Volkmar, F. R. (2009). Longitudinal assessment of autism spectrum disorders in toddlers with the modified checklist for autism in toddlers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(2), 237-246.