Introduction

Hyperammonemia, characterized by elevated plasma ammonia levels (above 80 µmol/L in infants up to 1 month and >55 µmol/L in older children), is a critical medical emergency in pediatrics. This condition poses an immediate threat to life due to its potential to induce severe neurological damage and cerebral edema. The primary causes in children are severe liver failure and inherited metabolic disorders. This article provides an updated review of the pathophysiology, current diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic management strategies for hyperammonemia in children, emphasizing medications, dialysis, and emerging treatment modalities relevant to critical care settings.

Pathophysiology of Hyperammonemia

Ammonia Metabolism in the Body

Ammonia (NH3) is a natural byproduct of protein breakdown, amino acid metabolism, and gut bacteria activity, serving as a major nitrogen source in the body. It is transported via the portal circulation to periportal hepatocytes, where approximately 90% enters the urea cycle for conversion into urea. Since ammonia itself is not readily excreted due to its poor water solubility, the remaining 10% is processed in perivenous hepatocytes. Here, ammonia combines with glutamate to form glutamine, facilitated by glutamine synthetase (GS), a system with lower capacity. Glutamine synthetase is also present in brain astrocytes, kidneys, and skeletal muscles, aiding in ammonia removal across various tissues.2 Glutamine is then either excreted through urine or utilized by the gut for energy production.3 Hyperammonemia arises when ammonia production overwhelms elimination, leading to systemic accumulation, brain influx, and subsequent neurological dysfunction.4

Mechanisms of Neurologic Impairment in Hyperammonemia

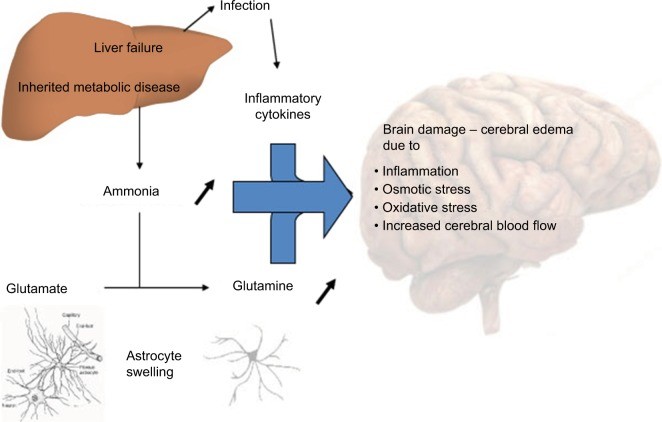

Figure 1.

Alt text: Diagram illustrating the proposed mechanisms of hyperammonemia-induced encephalopathy and cerebral edema, highlighting ammonia metabolism in astrocytes, glutamine accumulation, NMDA receptor activation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress.

Several hypotheses attempt to explain the neurological damage caused by hyperammonemia (Figure 1). At physiological pH, ammonia predominantly exists in its ionic form (NH4+), which poorly permeates cell membranes. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is significantly less permeable to NH4+ compared to the gaseous form, NH3 (approximately 5 times more permeable). Alkalosis can therefore exacerbate ammonia accumulation in the central nervous system.

Within astrocytes, glutamine synthetase converts ammonia to glutamine. Under normal conditions, GS operates near its maximum capacity and can become easily saturated. Glutamine is then released into the extracellular space via the sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter (SNAT5) and subsequently taken up by neurons. In neurons, glutaminase converts glutamine back to glutamate. Glutamate release into the synaptic cleft stimulates N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Overactivation of NMDA receptors leads to calcium influx, increased nitric oxide production, and excitotoxicity.5

Glutamine acts as an osmotic agent; its accumulation within astrocytes causes cellular swelling and cerebral edema. Reduced SNAT5 expression can further exacerbate this by trapping glutamine within astrocytes. Furthermore, neurotransmission disruption leads to excessive neuro-inhibition, contributing to encephalopathy. In mitochondria, glutamine is converted back to ammonia by phosphate-activated glutaminase. Ammonia is known to disrupt mitochondrial permeability, leading to mitochondrial swelling and dysfunction.6 Hyperactivation of NMDA receptors also triggers neurotoxic pathways that result in axonal degeneration and cellular death.5 Another proposed mechanism involves the activation of phosphatase calcineurin, which increases ATP consumption by up to 80% through Na/K ATPase dephosphorylation, inducing oxidative stress and cellular death.5 Finally, elevated brain ammonia levels may disrupt cerebral autoregulation, causing hyperemia.6

If left untreated, hyperammonemia can cause irreversible damage to the developing brain, leading to seizures, motor and cognitive impairments, cerebral palsy, and potentially death.

Diagnosis and Etiology of Hyperammonemia in Critical Care

Diagnostic Approach to Hyperammonemia

Acute hyperammonemia is often precipitated by protein catabolism resulting from prolonged fasting, fever, infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, dehydration, high protein intake, anesthesia, and surgical procedures. Clinical manifestations are diverse, ranging from digestive symptoms (nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, failure to thrive) to neuropsychiatric symptoms (headaches, ataxia, dysarthria, behavioral changes, neurodevelopmental delay, hypotonia). Severe cases may present with seizures, altered consciousness, and central hyperventilation. Signs of liver failure (jaundice, bleeding) and/or multiorgan failure (hypotension, oliguria) may also be observed. In neonates, clinical signs can be nonspecific, mimicking sepsis.

In any child presenting with unexplained neurological signs, measuring plasma ammonia levels is crucial. However, obtaining reliable ammonia measurements in clinical practice can be challenging. Most laboratories employ methods based on the amino reduction of α-ketoglutarate, which requires NADPH. The reduction rate is directly proportional to plasma ammonia levels, and NADPH concentration changes are measured spectrophotometrically. A critical limitation of this method is the stringent sample handling requirements: blood samples must be drawn without a tourniquet, immediately placed on ice, and rapidly transported to the lab, as ammonia is only stable for a short period.

False positive results are common due to preanalytical errors such as hemolysis or delays in sample processing. According to guidelines from the Urea Cycle Disorders Conference Group, if immediate assay is not possible, plasma samples should be stored at -70°C, and capillary samples should be avoided.8 Given these technical challenges and a positive predictive value of approximately 60%, repeat ammonia testing is recommended if hyperammonemia is initially detected.7,9

Neuroimaging plays a supportive role in diagnosing hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Cerebral computed tomography (CT) can rule out other critical conditions like intracranial hemorrhage or mass lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically reveals either a diffuse pattern affecting the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, thalami, and brainstem, or a central pattern involving the basal ganglia, perirolandic region, and internal capsule.10 Gunz et al.10 observed that extensive cerebral involvement on MRI correlated with poorer developmental outcomes in neonates with urea cycle defects (UCDs), although diffuse patterns were also seen in patients with milder outcomes. Central MRI patterns did not correlate with outcome. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), particularly apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, can be valuable in highlighting cytotoxic edema.11

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is a noninvasive technique to measure cerebral concentrations of specific biochemicals, particularly glutamine. MRS can also monitor treatment response by tracking glutamine levels.11,12

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) emerges as a valuable tool in hyperammonemic encephalopathy. TCD dynamically assesses cerebral blood flow, detects cerebral edema, and evaluates cerebral vascular resistance. Notably, cerebral blood flow may increase before overt signs of intracranial hypertension.13 Therefore, vigilant TCD monitoring can facilitate early diagnosis of intracranial hypertension. Clinical experience suggests TCD as a preferred method for routine, noninvasive cerebral blood flow monitoring to guide therapy.

Electroencephalography (EEG) in hyperammonemic newborns has shown similar features, such as multifocal spikes or paroxysmal activity during crises,13 but lacks specificity. Its main utility is in detecting seizures in comatose or sedated patients.

Etiological Investigations for Hyperammonemia

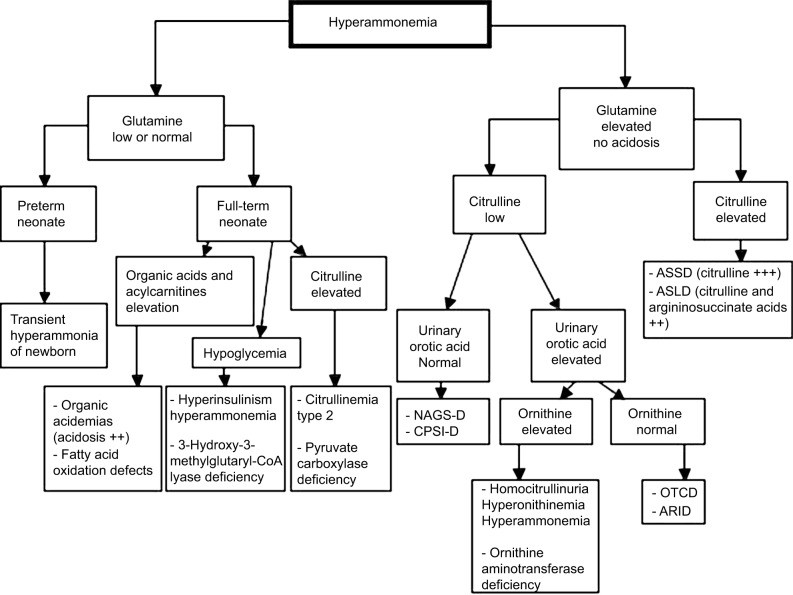

Figure 2.

Alt text: Diagnostic algorithm for hyperammonemia, outlining initial assessments, laboratory investigations including blood gas, electrolytes, liver function tests, amino acids, organic acids, and acylcarnitine profiles, and differentiation between liver failure, urea cycle defects, and other metabolic disorders.

Note: Adapted from Haberle J, Boddaert N, Burlina A, et al. Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:32.27

Abbreviations: AR1D, arginase 1 deficiency; ASLD, arginosuccinate lyase deficiency; ASSD, arginosuccinate synthetase deficiency; CPS1-D, carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 deficiency; NAGS-D, N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency; OTCD, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.

In pediatric intensive care, the causes of acute hyperammonemia are diverse, with liver failure being the most common (64%), followed by UCDs (23%), and other etiologies (13%) like toxic exposures and medications.1 Initial diagnostic workup involves clinical examination and laboratory investigations, including blood gas analysis, electrolyte and anion gap measurement, ketonuria, glycemia, lactic acid, liver enzyme and function tests (AST, ALT, bilirubin, GGT, factor V, prothrombin ratio, INR), renal function tests (BUN, creatinine), plasma and urine amino acid analysis, urine organic acid chromatography, plasma acylcarnitine profile on dried blood, total, esterified and free carnitine levels, and urinary orotic acid.

Acute Liver Failure (ALF) and Hyperammonemia

ALF is a significant cause of hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy (HE)14 (Table 1). Numerous primary liver diseases can lead to ALF and subsequent hyperammonemia if severe. Drug-induced liver injury, particularly acetaminophen, accounts for approximately 50% of ALF cases in the USA. A substantial proportion (18%–47%) remain of undetermined etiology.15 Inborn errors of metabolism are implicated in 10%–34% of pediatric ALF cases.15 Galactosemia typically presents in neonates after milk introduction, often mimicking Gram-negative sepsis. Diagnosis is confirmed by measuring galactose-1-phosphate levels or galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase enzyme activity in erythrocytes, or through genetic testing. Tyrosinemia often manifests as ALF around the second month of life, with characteristic nodular liver appearance on ultrasound. Hereditary fructose intolerance presents after fructose-containing food introduction, with liver and digestive symptoms and hypoglycemia. Other inborn metabolic errors causing liver failure include mitochondrial hepatopathies, fatty acid oxidation disorders, and congenital disorders of glycosylation. Viral infections, notably enteroviruses and herpes simplex virus, account for 6%–22% of ALF cases. Other etiologies include hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, fetal alloimmune hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis (giant cell hepatitis with autoimmune hemolytic anemia), and vascular diseases (veno-occlusive disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome). In the pediatric ICU, liver failure can also be secondary to multiorgan failure.

Table 1.

Comparison of Etiologies of Acute Liver Failure in Children Across Studies

| Causes | Bicêtre Hospital (1996–2006) Monocenter study 235 patients (n [%]) | PALF (1999–2008) Multicenter study 20 centers in the USA 703 patients (n [%]) | PALF (1999–2009) Multicenter study 24 centers (USA, Canada, UK) 148 patients ≤90 days (n [%]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | 81 (34%) | 68 (10%) | 28 (19%) |

| Infectious | 52 (22%) | 45 (6%) | 24 (16%) |

| Undetermined | 42 (18%) | 329 (47%) | 56 (38%) |

| Toxic | 32 (14%) | 111 (16%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Autoimmune | 15 (6%) | 48 (7%) | |

| Hematologic diseases | 10 (4%) | – | 5 (3.4%) |

| Vascular diseases | 3 (1%) | – | |

| Other diagnosis | – | 102 (14%) |

Note: Reproduced from Devictor D, Tissieres P, Afanetti M, Debray D. Acute liver failure in children. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35(6–7):430–437. Copyright ©2011, published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved.15

Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HHV6, herpes virus-6; HSV, herpes simplex virus; PALF, Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study Group.

Urea Cycle Defects (UCDs) and Hyperammonemia

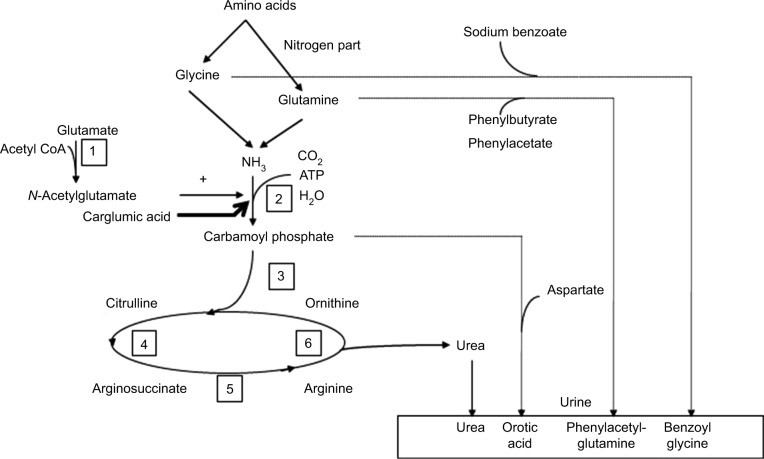

UCDs account for a significant proportion (23%) of acute hyperammonemia in critically ill children.1 Prevalence and incidence of these disorders vary geographically (Figure 3). UCDs can manifest as either acute or chronic hyperammonemia, depending on the severity of the enzyme deficiency. Most UCDs are diagnosed via plasma amino acid chromatography and can be detected through newborn screening programs.

Figure 3.

Alt text: Diagram of the urea cycle, illustrating the six enzymatic steps and associated urea cycle disorders (UCDs), numbered 1 through 6, along with pharmacological therapies targeting different points in the cycle to manage hyperammonemia.

Notes: Each number corresponds to a urea cycle deficiency disease: 1 = N-acetylglutamate synthase; 2 = carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1; 3 = ornithine transcarbamylase; 4 = arginosuccinate synthetase; 5 = arginosuccinate lyase; 6 = arginase deficiency.

Abbreviation: CoA, coenzyme A.

Specific Urea Cycle Defects

Ornithine Transcarbamylase (OTC) Deficiency: The most common inherited ureagenesis defect (>50% of UCDs), with a prevalence of 1 in 14,000 to 1 in 62,000–77,000 live births.16 OTC deficiency is X-linked. In males, it’s often lethal in the neonatal period, though milder forms exist. Females exhibit variable symptoms due to X-inactivation patterns; 15%–20% experience severe symptoms. In OTC deficiency, citrulline levels are low or normal, and urinary orotic acid is elevated.3,16

N-Acetylglutamate Synthetase (NAGS) Deficiency: An autosomal recessive disorder reducing carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) activity, causing hyperammonemia.17,18 Citrulline is normal or low, and urinary orotic acid is not increased. Carglumic acid, an NAGS analog, is the treatment of choice. In acute hyperammonemia, standard management should be initiated alongside carglumic acid administration.

CPS1 Deficiency: An autosomal recessive disorder biochemically indistinguishable from NAGS deficiency.19

Arginosuccinate Synthetase Deficiency (Citrullinemia Type I): An autosomal recessive disorder characterized by elevated citrulline and urinary orotic acid.

Arginosuccinate Lyase Deficiency: An autosomal recessive disorder with increased citrulline and arginosuccinic acid in plasma amino acids.20 This is unique among UCDs for its high incidence of neurological complications even without hyperammonemia, and progressive chronic liver disease and fibrosis.21

Arginase 1 Deficiency: An autosomal recessive disorder leading to arginine accumulation in plasma amino acids and elevated urinary orotic acid. Acute hyperammonemia is less common; patients typically present with progressive spasticity, intellectual disability, and sometimes seizures after age two.3

Organic Acidurias (OA) and Hyperammonemia

OA are autosomal recessive inherited disorders mainly affecting branched-chain amino acid degradation. Hyperammonemia in OA results from decreased acetyl-CoA and inhibition of NAGS and CPS1 activities22 by toxic metabolites. These conditions are characterized by hyperammonemia accompanied by severe metabolic acidosis with high anion gap and ketonuria. Diagnosis is made by urinary organic acid chromatography and plasma acylcarnitine profile.

Other Causes of Hyperammonemia

Other inherited metabolic diseases, such as fatty acid oxidation defects, can cause hyperammonemia, possibly due to generalized mitochondrial dysfunction7 and acetyl-CoA deficiency from blocked acylcarnitine degradation.22 These disorders often manifest with acute liver disease, hypoglycemia, elevated creatine kinase, and cardiomyopathy, alongside hyperammonemia. HMG-CoA lyase deficiency combines features of organic acidemia and fatty acid oxidation defects. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency and other mitochondrial defects may also present with liver failure and hyperammonemia. Lactic acidosis warrants cautious use of intravenous glucose and insulin. Hyperammonemia is also seen in lysinuric protein intolerance. Citrin deficiency is a specific metabolic disorder where high-carbohydrate diets can induce hyperammonemia, requiring a distinct management approach.23

Perinatal asphyxia has been identified as a cause of hyperammonemia due to hypoxic stress, which can increase catabolism and reduce hepatic urea synthesis, leading to mild hyperammonemia. In a study of 100 patients with perinatal asphyxia, 20% had hyperammonemia >90 µmol/L, with a mean level of 117±41 µmol/L in asphyxia stages 2 and 3.24

Transient hyperammonemia of the newborn (THAN) is a condition of potentially severe hyperammonemia caused by transient platelet activation and portosystemic shunting through a large ductus venosus. Neurological outcomes can range from normal development to severe intellectual disability and seizures.3,24 Favorable neurological outcomes are achievable with prompt treatment.7 Drug-related causes of hyperammonemia include valproic acid (interferes with glutamine synthesis), carbamazepine, salicylates (Reye’s syndrome25), topiramate, tranexamic acid, and chemotherapy agents.

Acute Management and Critical Care Treatment of Hyperammonemia

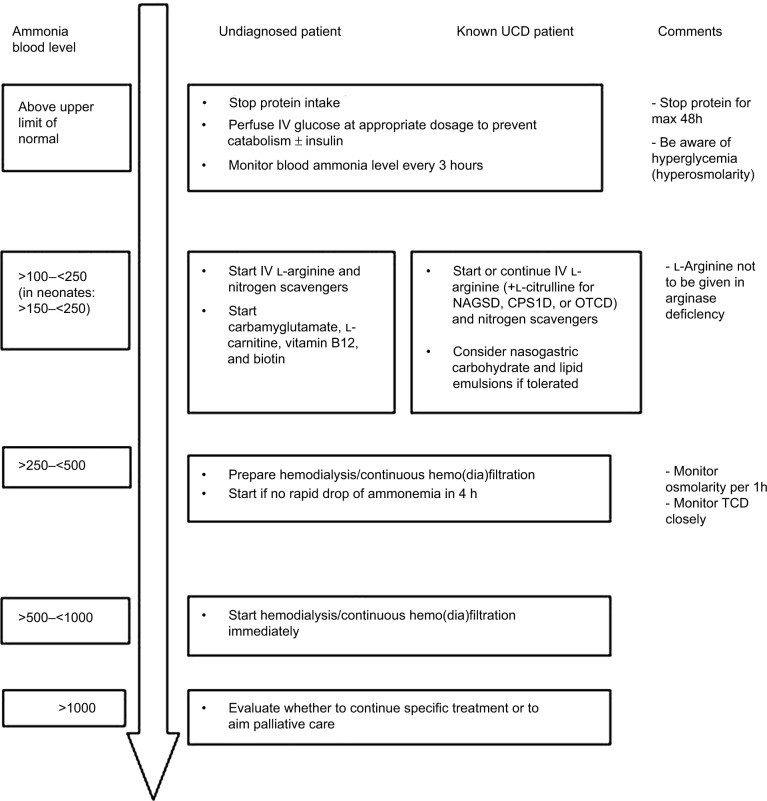

Therapeutic interventions for hyperammonemia aim to rapidly reduce plasma ammonia levels and protect the brain from ammonia toxicity (Figure 4). Prompt diagnosis and management are crucial to minimize the risk of irreversible brain damage. Patients suspected of hyperammonemia should be quickly transferred to pediatric ICUs equipped with readily available first-line medications and established protocols. Coma duration and peak ammonia levels are primary determinants of neurological outcome.22 Plasma ammonia concentrations above 300 µmol/L are generally considered severe, but levels above 200 µmol/L within 48 hours of ICU admission are a better predictor of 28-day mortality (odds ratio 5.07; 95% CI [1.22–21.02]).4 Hyperammonemia lasting >3 days is a major risk factor for cerebral edema, according to Kumar et al.26 While no definitive prognostic ammonia threshold exists, aggressive and sustained efforts to control elevated ammonia levels are essential in all management protocols.

Figure 4.

Alt text: Algorithm for managing symptomatic hyperammonemia patients in critical care, detailing initial stabilization, ammonia lowering therapies including protein restriction, intravenous medications like sodium benzoate and sodium phenylacetate, dialysis considerations, and specific treatments for urea cycle disorders.

Source: Adapted from Haberle J, Boddaert N, Burlina A, et al. Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:32.27

Abbreviations: CPS1D, carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 deficiency; IV, intravenous; NAGSD, N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency; OTCD, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; TCD, transcranial Doppler; UCD, urea cycle defect.

Initial Critical Care Management of Hyperammonemia

The initial step in managing hyperammonemia involves immediately stopping all protein intake for 24–48 hours. Simultaneously, ensure adequate hydration with high glucose content (10% dextrose) at 1–1.5 times maintenance rates to provide sufficient calories, promote anabolism, and reverse catabolism. Continuous glucose infusion may be initiated at 8–10 mg/kg/min in neonates. Insulin can be added, if necessary, to maintain normoglycemia, considering the presence of lactic acidosis which requires careful glucose and insulin administration. Intravenous lipids (1–2 g/kg/day) can be introduced to achieve a caloric intake of 130–150 kcal/kg/day in neonates or 1,500 kcal/m²/day, after ruling out fatty acid oxidation defects. Enteral feeding should be initiated as soon as feasible with a formula composed of carbohydrates and lipids to maximize caloric intake. Once blood ammonia levels fall below 100 µmol/L, protein can be cautiously reintroduced, starting at 0.4–0.5 g/kg/day, and gradually increased under close clinical and ammonia level monitoring, guided by genetic and nutritional specialists.

Nitrogen-scavenging medications are crucial for managing hyperammonemia caused by inborn errors of metabolism and can also aid in reducing ammonia levels in ALF (Figure 3). Sodium benzoate combines with glycine to form hippurate, which is excreted in the urine. A bolus dose of 250 mg/kg over 90–120 minutes is followed by a maintenance infusion of 250–500 mg/kg/day.27 Sodium phenylacetate or sodium phenylbutyrate binds with glutamine to form phenylacetylglutamine, also eliminated in urine, with similar dosing as sodium benzoate.27 Ammonul® (Ucyclyd Pharma Inc, Scottsdale, AZ, USA), an intravenous formulation combining sodium benzoate and sodium phenylacetate, contains a significant sodium load, as do all intravenous NH3 scavengers.28

Adjunct Treatments for Hyperammonemia

Lactulose and specific antibiotics are utilized in hepatic encephalopathy to decrease ammonia levels. Lactulose acidifies the colonic environment, promoting the conversion of NH3 to NH4+, reducing its absorption and creating a less favorable environment for urease-producing bacteria. However, its effectiveness remains debated.29 Lactulose is generally not used in inherited metabolic disorders causing hyperammonemia. Rifaximin, a broad-spectrum oral antibiotic effective against both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, can inhibit ammonia-producing gut bacteria.30 Neomycin inhibits glutaminase activity in the intestinal mucosa, reducing ammonia production, but carries risks of ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and enterocolitis.31 Oral metronidazole and vancomycin also target anaerobic gut flora, reducing ammonia production. Except for rifaximin, these antibiotics are typically used in conjunction with lactulose.31 Probiotics are used to promote non-urease-producing bacteria in cirrhotic patients and may reduce blood ammonia levels in long-term management, although their impact on clinical outcomes is not definitively established.29

Intravenous L-arginine and L-citrulline can enhance nitrogen excretion via the urea cycle. Arginine becomes an essential amino acid in UCDs (except arginase deficiency). The recommended L-arginine dosage is a 250–500 mg/kg bolus over 90–120 minutes, followed by a 250 mg/kg/day maintenance dose.27

L-carnitine is essential for fatty acid beta-oxidation, facilitating mitochondrial energy metabolism and acetyl-CoA production. It is crucial in treating OA and can be administered intravenously at 200 mg/kg/day in undiagnosed hyperammonemia. Studies in rats using MRS have shown L-carnitine improves mitochondrial energy metabolism in the brain and muscles.32

Neuroprotective Strategies in Critical Care

Critically ill, comatose children with hyperammonemia should be presumed to have cerebral edema and managed accordingly. This includes elevating the head to 30°, maintaining a neutral neck position, providing sedation and analgesia to prevent agitation, and initiating mechanical ventilation based on coma severity. Sedative agents must be carefully chosen and dosed due to potential accumulation in liver and/or renal dysfunction. Short-acting agents like propofol or fentanyl are preferred. Alpha-2-agonists (e.g., clonidine) have been explored for their potential to reduce glutamate release, thereby decreasing NMDA receptor activation and hyperexcitability. Calligaris et al. reported the efficacy of intravenous clonidine in a 7-month-old infant with UCDs.33

Cerebral perfusion monitoring with TCD is beneficial for detecting decreased cerebral blood flow due to intracranial hypertension. The use of intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring in children remains debated due to hemorrhagic risks, especially in ALF, despite its value in monitoring cerebral edema.

Osmolarity should be closely monitored, and osmotic agents considered to reduce cerebral edema.

Dialysis in Hyperammonemia Management

Dialysis is indicated if ammonia levels remain >500 µmol/L or fail to decrease despite 4 hours of optimal medical management.27,34,35 Conventional hemodialysis (HD) has been shown to achieve significantly faster ammonia reduction rates within 4 hours compared to continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) (p<0.001).34 HD is therefore the preferred dialysis modality for rapid ammonia reduction in severe hyperammonemia. HD is often followed by CVVHD for ongoing ammonia control.27,35 Osmolarity shifts during HD pose a risk, particularly in infants. Careful hourly osmolarity monitoring during HD is crucial, and dialysate composition should be adjusted to prevent rapid osmolarity decreases to avoid cerebral herniation.36 Peritoneal dialysis has limited efficacy in ammonia removal in children.35

Novel and Emerging Therapies

Therapeutic hypothermia for ICP control in ALF with hyperammonemia has shown promise in animal models, extending survival, preventing brain edema, and reducing CSF ammonia levels. Mild hypothermia may limit ammonia transport across the BBB. Jalan et al. studied mild hypothermia (32°C–35°C) in adult ALF patients, observing a significant reduction in mean ICP from 36.5±2.7 mmHg to 17±0.9 mmHg within 4 hours, sustained thereafter.37,38 Lichter-Konecki et al., in a small study of 14 children with UCDs, reported faster ammonia reduction in patients treated with CVVHD and hypothermia compared to those with CVVHD and normothermia, without unexpected adverse events.39

Liver transplantation remains a critical option for ALF with severe hyperammonemia when detoxification measures are inadequate, or as an elective procedure for certain inborn errors of metabolism.

Carbamylglutamate, a synthetic analog of N-acetylglutamate (NAG), can be beneficial in NAGS deficiency. It can reduce ammonemia by substituting for NAG, an essential cofactor for CPS1. NAGS deficiency can be primary genetic or secondary to OA. Carbamylglutamate may stimulate residual CPS1 activity when partially deficient.40,41 Its safety, rapid action, and oral administration have led some to advocate for its early use in severe hyperammonemia, even before definitive diagnosis.27,28,40,42,43 Initial dosing is 200 mg/kg (range 100–300 mg/kg) bolus via nasogastric tube, followed by 200 mg/kg every 3–6 hours. L-ornithine-L-aspartate enhances the urea cycle in residual hepatocytes, promoting ammonia detoxification. L-ornithine can also be converted to glutamate, which removes ammonia. However, its clinical efficacy remains debated and is not currently standard care.29 L-ornithine phenylacetate activates the urea cycle and glutamine synthase and conjugates glutamine and glycine for elimination. Animal studies show it reduces blood and cerebral ammonia and ICP. A phase I study in cirrhotic patients showed mild adverse effects and a 50% reduction in blood ammonia within 36 hours under continuous infusion.29

Flumazenil, due to its anti-GABAergic activity, has been considered for HE, but a meta-analysis found no mortality reduction or clinical improvement in HE patients.44 Flumazenil may be considered in selected HE patients with chronic liver disease.31

Activated carbon microparticles have demonstrated reduced intestinal ammonia absorption and lower blood ammonia levels in animal and human studies.29

Gene therapy is a future direction for genetic diseases. Studies in animal models are ongoing, including adeno-associated virus vector delivery of OTC in OCTD mouse models, showing enzymatic activity restoration and ammonia level control. 45–47 A clinical trial in adults with late-onset OTCD is underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02991144).

Cell therapy aims to repopulate livers of UCD patients with functional hepatocytes.29 Bioartificial livers represent another promising future treatment for acute hyperammonemia.48

Conclusion: Critical Care for Hyperammonemia Requires Prompt Diagnosis and Multidisciplinary Treatment

Hyperammonemia should be rapidly suspected in children presenting with neurological symptoms. Immediate and appropriate management is essential, as coma duration and peak ammonia levels are major determinants of outcome. Effective critical care for children with hyperammonemia necessitates a multidisciplinary approach, involving geneticists/metabolic specialists, nephrologists, intensivists, neurologists, pharmacists, and nutritionists. Even in ALF, nitrogen scavengers can be valuable in reducing ammonia levels, often in conjunction with dialysis, depending on ammonia level trends.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Jouvet has presented at conferences supported by Medunik Inc and Air Liquide Santé. Philips Medical lent medical devices to Dr. Jouvet.

Footnotes

Disclosure

P. Jouvet has received financial support from the Fonds de Recherche Santé Québec and from the Quebec Ministry of Health as well as from Sainte-Justine University Hospital. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.