Introduction

Global healthcare expenditure has been on a continuous rise, projected to escalate from US$7.9 trillion in 2017 to a staggering $11.0 trillion by 2030. This surge is further highlighted by the annual healthcare spending growth rate of 4.0% between 2000 and 2015, significantly outpacing the global economy’s growth rate of 2.8%. Hospital service expenses constitute a substantial portion of this expenditure across nations, irrespective of their economic status. The Asia-Pacific region is increasingly becoming a major contributor to global medical supply and demand. Simultaneously, low- and middle-income countries are facing a sustainability crisis due to prevailing health spending patterns. Optimizing health expenditure per capita can be achieved through effective measures like decreasing out-of-pocket payments (OOP). Provider payment methods play a pivotal role in healthcare resource allocation. Reforming hospital payment mechanisms can lead to significant efficiency gains, influencing the behaviors of both healthcare providers and patients, and contributing to broader health system objectives.

Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) represent a critical hospital payment mechanism, alongside fee-for-service models, global budgets, capitation payments, and hybrid approaches. DRGs categorize patients into groups based on clinical similarities such as age, gender, disease severity, complications, comorbidities, and resource consumption, ensuring comparable expenses within each group. This classification implies that patients within the same DRG are medically and economically alike. Originating in the US in 1983 as a prospective case-based reimbursement system, DRG-based payment systems have since been adopted globally to manage healthcare costs, particularly in Europe, rapidly developing Asian nations, and sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately 25 countries worldwide employ similar case-mix models. This payment system provides a fixed reimbursement for each Medicare patient, irrespective of the actual treatment cost, thereby promoting hospital performance transparency and resource efficiency through standardized reimbursement. This system aims to enhance efficiency by minimizing unnecessary services and boosting productivity. Furthermore, DRGs enhance transparency, enabling quality and efficiency comparisons among hospitals based on case-mix index-measured morbidity. They also prospectively determine patient OOP payments for inpatient care, thus controlling patient cost burdens. Previous research suggests that DRG-based payments can modestly improve efficiency and control costs without significantly compromising healthcare quality, provided close monitoring is in place. However, some evidence indicates potential compromises in equity and healthcare quality, especially for patients not covered under DRG schemes, despite slight efficiency improvements. A systematic review highlighted that while DRG-based payment improves healthcare efficiency by reducing length of stay (LOS), its impact on healthcare quality remained ambiguous. Although a meta-analysis by Meng et al. assessed DRG-based payment effectiveness on LOS and readmission rates, it did not explore other quality of care outcomes.

Significant advancements in hospital technology and the evolution of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system have facilitated the worldwide adoption of DRG-based payment systems. Nevertheless, their precise effects on healthcare quality and overall efficacy are still not fully understood. Prior systematic reviews have either focused on the development of DRG-based payment systems without assessing their impact on medical care, or lacked specific focus on DRG-based payments. Consequently, there is a limited body of research in this area. This meta-analysis was conducted to thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of DRG-based payment on inpatient care quality. The findings are expected to support informed decision-making and contribute to better guidelines for implementing DRG-based reimbursement systems.

Methods

Registration

This meta-analysis was pre-registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020205465) and adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis) guidelines for network meta-analysis checklists.

Search Strategy

Two independent researchers conducted comprehensive searches across PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), NHS Economic Evaluation, Global Health, and Health Policy Reference Center. The search spanned from database inception up to December 30, 2022. Keywords used for DRG searches included: “diagnosis-related group*,” “DRGs,” “diagnosis related group*,” and “case mix.” For other patient classification-based payment systems, keywords “GHM,” “DBC,” “HRG,” and “LKF” were employed. The detailed search strategy is available in Additional File 1: Appendix 1. Reference lists of relevant reviews were also consulted to identify additional eligible studies. No restrictions were placed on publication status or date.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) Participant type: Inpatients of all ages and genders, with diverse medical conditions and clinical procedures. (2) Study design: Designs approved by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC), such as interrupted time series studies (ITS), randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials (non-RCTs), controlled before-after studies (CBA), and uncontrolled before-after studies (BA). (3) Interventions: Payment systems based on DRGs or similar patient classifications (e.g., DBC, HRGs, LKF) applied at institutional, regional, or individual levels within tertiary, secondary, or primary care settings for inpatient service reimbursement. Studies focusing on the Japanese diagnosis procedure combination system (DPC), a mixed reimbursement system with prospective and cost-based elements including a flat-rate per diem based on diagnosis categories, were excluded. (4) Comparisons: Studies comparing DRG-based payment with cost-based payment systems. Cost-based payment criteria included: (a) retrospective payment; (b) cost-based hospital reimbursement; (c) per service payment unit. (5) Outcomes: Primary outcomes of interest were healthcare quality indicators (including 30-day readmission, in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, 30-day mortality, etc.) and efficiency metrics (e.g., LOS).

Studies lacking specific data, such as protocols, conference abstracts, proceedings, and commentaries, were excluded.

Study Selection

EndNote X7 was used to manage literature search records. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts against selection criteria, removing duplicates. Potentially eligible and overlapping studies underwent full-text review. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer provided the final decision when consensus could not be reached.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently used a standardized form to extract data, including: first author, publication year, country, setting, diagnosis, outcome measures, sample size, mean age, estimation method, payment type, and policy details for each country.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed bias risk in included studies using EPOC methods. Studies were categorized as having high, low, or unclear risk of bias. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate cohort study quality based on selection, comparability, and outcome parameters. Quality was assessed for each item; consistent items received one point, while inconsistent, uncertain, or unmentioned items received zero. The highest NOS score was 9; scores below 6 were considered low quality, and above 6 as high quality. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Statistical Analyses

Standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used for continuous outcome variables. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ .05. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs were calculated for dichotomous outcomes using the Mantel-Haenszel method. Relative difference change with 95% CI was used for ITS outcomes, measured by step change (immediate DRG-based payment effect) and slope change (long-term effect). The conversion formula from absolute to relative difference change is in Additional File 1: Appendix 2. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics and Higgins I2 test. A random effects model was used if heterogeneity was statistically significant (P for I2 > 50%); otherwise, a fixed effects model was applied. Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were used to explore heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was conducted for the primary outcome across different study designs, age groups (mixed age vs. ≥65 years), and DRG implementation length. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.0.

Results

Study Selection

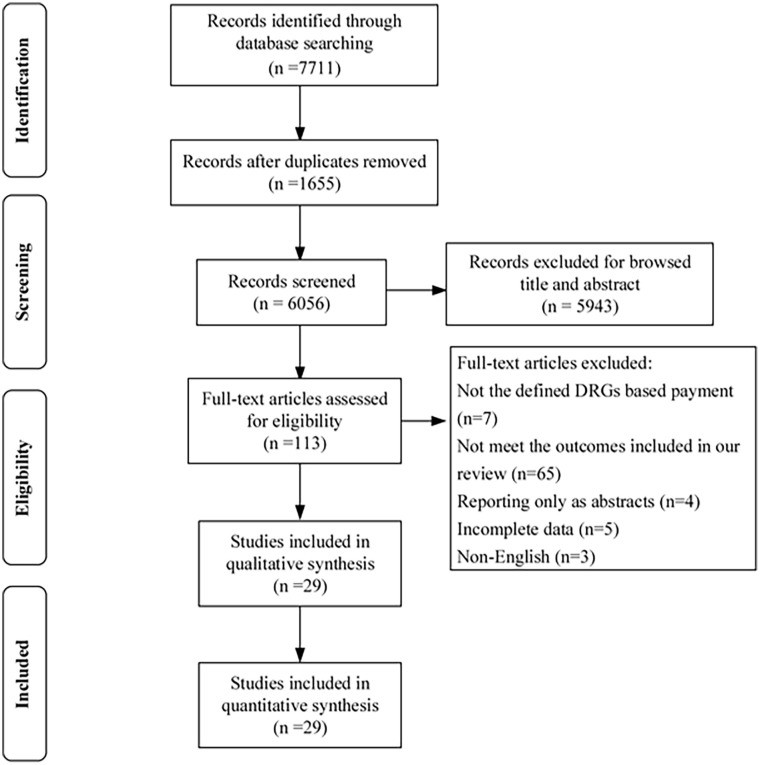

The initial search yielded 7711 potentially relevant articles, reduced to 6056 after removing duplicates. Title and abstract screening based on inclusion/exclusion criteria led to 113 records for full-text review. Ultimately, 29 studies were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The 29 studies comprised fifteen cohort studies, nine CBA studies, and five ITS studies, encompassing 36,214,219 patients, published between 1988 and 2019. Five studies (17.2%) focused on pneumonia, five (17.2%) on appendicitis, and three (10.3%) on psychosis. Participant ages ranged from 5 to 77 years, primarily from the United States, China, Korea, and Switzerland. DRG systems varied in implementation conditions, details, and timelines, including start year and study period. Seventeen studies reported full DRG adoption, with a median study period of 30 months. DRG implementation varied across countries for different disease groups, with varying complexity levels and reimbursement rates. In total, 26 trials (89.7%) reported length of stay, 10 trials (34.5%) reported 30-day readmission, and 5 trials (17.2%) reported in-hospital mortality. Detailed characteristics of each trial are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies on Diagnosis Related Groups and Quality of Care.

| Study | Participants (Number, Gender(F/M), Age) | Study design | Hospital type | Diagnosis/procedures | DRG | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years started DRGs | Study periods after DRGs adoption | Implementation condition of DRGs | Some details of DRGs implementation | |||

| Kim 2014, Korean | DRG, 212, 118/94;34.27 ± 18.29CON, 204 119/85; 36.72 ± 19.07 | Retrospective cohort study | Medical center | Acute or other appendicitis and underwent a procedure of appendectomy | 2013 | 6 months |

| Schwartz 1998, United States | DRG, 145, 73/72; mean age 68CON, 301 154/147; mean age 68 | Cohort study | Private hospital | Colorectal cancer surgery | 1987 | 12 months |

| Simons 1988, United States | DRG, 31, NA; 74.9 ± 8.00CON, 25, NA; 74.3 ± 7.57 | Cohort study | Medical center | Primary or secondary diagnosis of pneumonia | 1984 | 12 months |

| Yuan 2018, China | DRG, 2168, 1692/476; 61.99 ± 14.08CON, 727, 566/160; 62.18 ± 13.27 | Retrospective cohort study | Tertiary hospital | Acute myocardial infarction | 2009 | 9 years |

| Jeon 2019, Korean | DRG, 3450, NA; 66.53 ± 9.45CON, 3912, NA; 65.69 ± 9.93 | Retrospective cohort study | Tertiary hospital | Undergo hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse | 2013 | 4 years |

| Jung 2018, Korean | DRG,16 760, NA; NACON,18 369, NA; NA | Retrospective cohort study | Tertiary hospital | Undergo C-secs, hysterectomies, and adnexectomies | 2013 | 1 year |

| Kim 2016, Korean | Large hospitals: DRG,30 884, 15 883/15 001;≧20 CON,189 349,96 302/93 047;≧20Small hospitals: DRG,16 327, 8335/7992; ≧20 CON, 43 502, 21 558/21 944;≧20 | Retrospective cohort study | Large hospital: Tertiary hospitalSmall hospital: Regional hospital | Appendectomy | 2012 | 2 years |

| Kim 2015, Korean | DRG, 354, 197/157; 29.7 ± 15.8)CON, 253, 139/114; 29.6 ± 14.5 | Retrospective cohort study | University-affiliated hospital | Undergo laparoscopic appendectomy | 2013 | 1 year |

| Thommen 2014, Switzerland | DRG, 412, 222/190; 76 (66-83)CON, 429, 205/224; 77 (66.7-83.6) | Prospectivecohort study | Tertiary hospital | Community-acquired pneumonia, acute heart failure, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or hip fracture | 2012 | 1 year |

| Weissenberge 2013, Switzerland | DRG, 175, 80/95; 65.2 ± 25.3CON, 275, 134/141; 74.8 ± 13.4 | Cohort study | University-affiliated hospital | Community-acquired pneumonia, acute heart failure, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and total prosthesis of the hip | 2012 | 1 year |

| Kutz 2019, Switzerland | DRG,1 408 318,730 228 /678 090; 70 (56-81)CON,1 018 404,531 226/487 178; 69 (55-80) | Cohort study | General hospital | Community-acquired pneumonia, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, and pulmonary embolism | 2012 | 1 year |

| Kwak 2017, Korea | DRG-AT, 490, 298/192; 6.61 ± 3.04; CON-AT, 485, 313/173;6.74 ± 4.73DRG-T, 224, 108/116; 24.87 ± 15.19; CON-T, 203, 90/113; 27.16 ± 11.16 | Cohort study | Tertiary hospital | Adenotonsillectomy and tonsillectomy | 2013 | 1 year |

| Zhang 2016, China | DRG, 75, 45/30; 40.0 ± 10.4CON, 133, 72/61; 37.9 ± 13.1 | Cohort study | Primary, secondary and tertiary hospital | Acute uncomplicated appendicitis with no complications | 2013 | 3 years |

| Moon 2015, South Korea | DRG,30; 18/12;12.9(5-18)CON,30; 19/11;13.4(6-18) | Cohort study | Every class of hospital | Pediatric appendicitis | 2013 | 28 months |

| Schuetz 2011, Switzerland | DRG, 259, 154/105; 66 ± 18.2CON, 666, 390/276; 68 ± 17.8 | Cohort study | NA | Community-acquired pneumonia | 2006 | 5 years |

| Ellis 1995, USA | DRG, 3204, 1227/1977;15-64CON,10 500, 3852/6648; 15-64 | CBA | General hospital | Psychiatric patients | 1989 | 3.5 years |

| Lave 1988, USA | DRG,66 268, NA; >65CON,93 627, NA; >65 | CBA | General health | Psychiatric patients | 1984 | 1 year |

| McCue 2006, United States | DRG, 120, NA; NACON, 26, NA; NA | CBA | Rehabilitation hospital | Patients requiring extensive rehabilitation services | 2002 | 1 year |

| Mayer-Oakes 1988, United States | DRG, 258, 124/134; ≧65CON, 140, 71/69; 50-64 | CBA | Community Hospitals | Patients requiring intensive care services | 1983 | 2 years |

| Lang 2004, Taiwan | DRG,15 499, 6178/9321; 53.46 ± 15.03CON,11 507, 4595/6912; 54.20 ± 14.93 | CBA | Medical center, regional, district hospital | Laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy | 1997 | 2 year |

| Zhang2010, China | 14 000, NA; NA | CBA | A+ class hospital | 13 diseases including Appendicitis | 2004 | 2 years |

| Cheng 2012, Taiwan | DRG,10 824, 7923/2901; NACON,28 415,19 294/9121; NA | CBA | NA | Cardiovascular diseases | 2010 | 1 year |

| Jian 2015, China | DRG,141 263,73 033/68 230; NACON,124 400,65 434/58 966; NA | CBA | Tertiary hospital | Cerebral ischemia, Lens surgery, Vascular procedures, Unilateral uterine adnexectomy | 2011 | 1 year |

| Jian 2019, China | DRG, 1374, 1082/292; ≧19CON, 1351, 1129/222; ≧19 | CBA | Tertiary hospital | Acute myocardial infarction care | 2011 | 1 year |

| Hu 2015, Taiwan | DRG, 495, NA; NACON, 272, NA; NA | ITS | Tertiary hospital | Type I tympanoplasty | 2010 | 3 years |

| South 1997, Australia | 11 939, 7522/4417; 5.4-5.48 | ITS | General hospital | Asthma | 1993 | 4 years |

| Muller 1993, USA | NA, NA; >65 | ITS | Community hospital | NA | 1983 | 10 years |

| DesHarnais 1990, USA | NA, NA; >65 | ITS | General hospital | Psychiatric patients | 1984 | 4 years |

| Vuagnat 2018, France | 32 921 156, NA; 48.6-51.3 | ITS | General hospital | All surgical procedures | 2005 | 4 years |

Quality Assessment

All nine CBA studies were assessed to have a high risk of bias in random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Two studies lacked sufficient information on baseline characteristics and outcome measurements. All studies demonstrated low risks of bias in contamination protection and outcome assessment. Three studies did not explicitly report differences between intervention completers and non-completers, and due to disparities in dropout rates between intervention and control groups, they were rated as having an unclear risk of attrition bias. Two studies were assigned an unclear risk of reporting bias. Among ITS studies, one was considered at high risk of bias due to potential outcome influence from a concurrent policy on peer review organization restructuring for quality monitoring, alongside DRG-based payment. Among cohort studies, two scored 6, five scored 7, and eight scored 8 on the NOS scale. The NOS item “the results of follow up were long enough” scored less than 40% in these studies, while other items scored above 80%. Detailed bias risk assessments are in Additional File 1: Appendix 3.

Meta-Analysis

DRG Impact on Length of Stay (LOS)

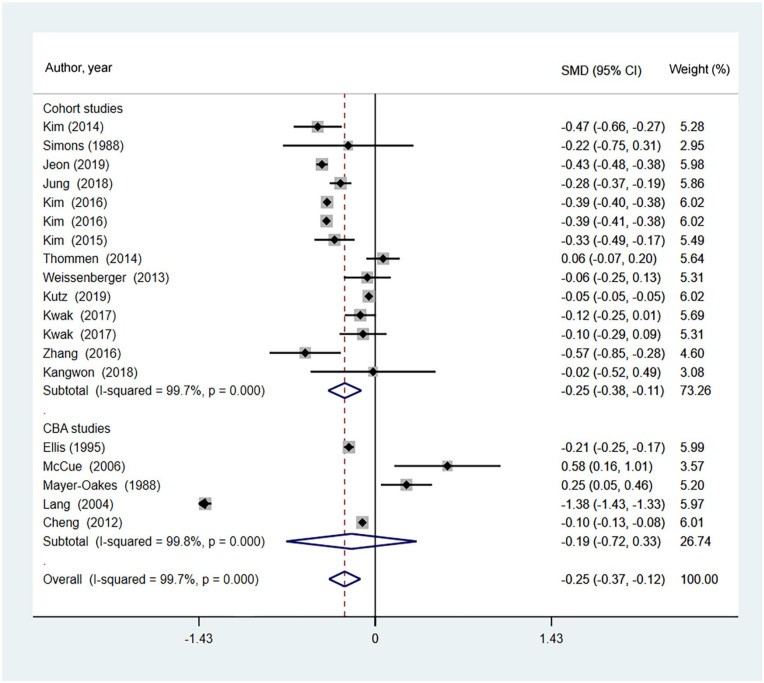

Seventeen studies, comprising 12 cohort and 5 CBA studies, examined the changes in LOS following DRG-based payment implementation (Figure 2). A random-effects model analysis indicated that DRG-based payment effectively reduced LOS (pooled effect: SMD = −0.25, 95% CI = −0.37 to −0.12, Z = 3.81, P < .001). Subgroup analysis by study design showed cohort studies significantly reducing LOS (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI = −0.40 to −0.14, Z = 4.04, P < .001), while CBA studies did not show a significant reduction (SMD = −0.19, 95% CI = −0.72 to 0.33, Z = 0.72, P = .474). Five ITS studies showed DRG-based payment associated with a significant LOS reduction (RDC = -10.76, 95% CI = −18.54 to −2.98, Z = 2.71, P = .007) (Supplemental Figure 1). Subgroup analysis by age showed significant LOS reduction in mixed-age studies (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI = −0.41 to −0.13, Z = 3.77, P < .001) but not in older age studies (SMD = −0.17, 95% CI = −0.40 to 0.05, Z = 1.59, P = .111; Pinteraction = .487). Furthermore, subgroup analysis by DRG implementation length showed significant LOS reduction in studies with shorter implementation (SMD = −0.30, 95% CI = −0.45 to −0.15, Z = 3.95, P < .001) and longer implementation (SMD = −0.21, 95% CI = −0.37 to −0.04, Z = 2.45, P = .014; Pinteraction = .093). Meta-analysis of CBA studies did not indicate a significant LOS decrease post-DRG implementation (SMD = −0.19, 95% CI = −0.72 to 0.33, Z = 0.72, P = .474). Finally, LOS for appendectomy inpatients decreased after DRG-based payment (Supplemental Figure 2).

DRG Impact on Readmission Rates

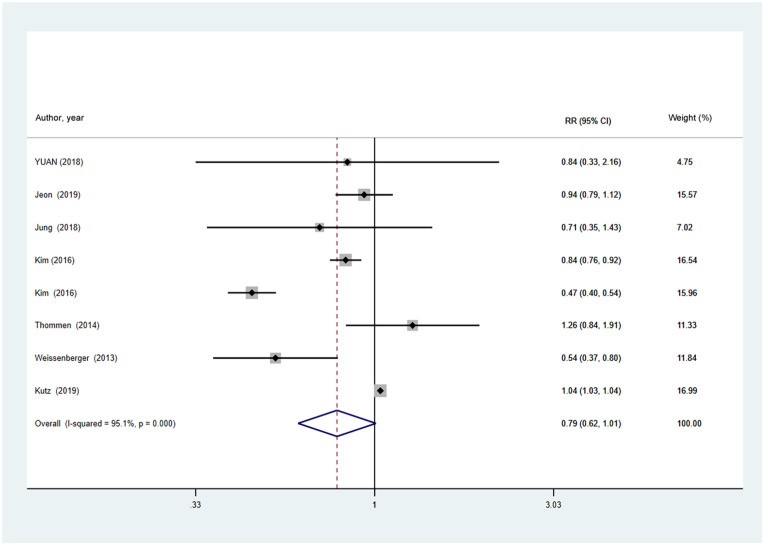

Seven cohort studies investigated the relationship between DRG-based payment and 30-day readmission rates. Meta-analysis indicated no significant overall effect on 30-day readmission rates following DRG-based payment (RR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.62-1.01, Z = 1.89, P = .058) (Figure 3). Meta-analysis of three studies focusing on community-acquired pneumonia, acute heart failure, or COPD exacerbation showed no significant increase in readmission rates after DRG-based payment (Supplemental Figure 3). No significant subgroup effects were found for DRG implementation length (Pinteraction = .616) or age (Pinteraction = .248) (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2- Appendix 4).

DRG Impact on Mortality Rates

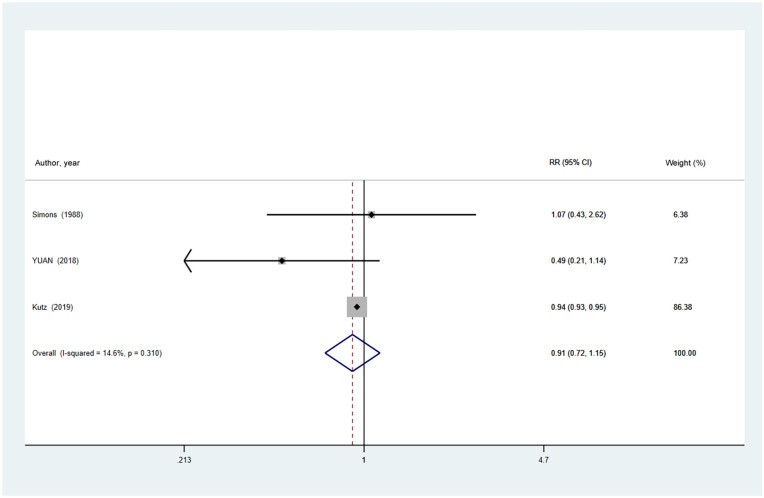

Only three cohort studies reported on the association between DRG-based payment and in-hospital mortality. Meta-analysis revealed no significant overall effect on mortality rates after DRG-based payment implementation (RR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.72-1.15, Z = 0.82, P = .411) (Figure 4).

Discussion

This meta-analysis assessed existing research on DRG-based payment implementation and its impact on inpatient healthcare quality. By synthesizing available data, the study demonstrated a significant reduction in LOS for patients following DRG-based payment adoption. However, it found no compelling evidence of adverse effects regarding readmission or in-hospital mortality, although some literature suggests potential detrimental impacts on these outcomes under certain conditions.

The findings indicate that DRG-based payment effectively reduces LOS, aligning with policy objectives and theoretical expectations. Consistent with this, multiple systematic reviews have established that DRG-based payments lead to significant LOS reductions. Subgroup analysis by DRG implementation length revealed variations in LOS results, potentially due to time lags between implementation and patient outcome changes. Prior research suggests that LOS initially decreases with DRG-based payment but stabilizes thereafter. Extended LOS is often linked to profit maximization in hospital reimbursement systems with fixed prices per case, whereas under DRG-based payment, longer stays reduce average profits. Therefore, DRG system implementation may encourage behavioral changes, promoting more efficient discharge planning. Reduced LOS can positively impact per-case costs, enhancing efficiency, productivity, and hospital profits under DRG-based payment. However, earlier research suggests that inappropriate premature discharges might increase under DRG-based payment to cut costs and maximize profits. While reducing LOS can be beneficial, concerns exist about potential adverse effects on healthcare quality through early discharges and service intensity reduction, possibly withholding necessary patient services. Conversely, Jian et al. reported no LOS reduction after DRG-based payment implementation. Similarly, Thommen et al.’s review indicated stable or slightly increased LOS shortly after SwissDRG implementation. Thus, caution is needed to ensure that new systems do not degrade medical service quality. Consequently, larger, well-powered studies are needed to confirm the positive impact of DRG-based systems on LOS.

This meta-analysis found no overall effect on readmissions after DRG-based payment implementation, consistent with previous reports by Epstein et al. and Palmer et al. A Korean study also found that DRG payments reduced LOS without increasing readmission rates. Similarly, other studies reported no significant differences in readmission and mortality post-system implementation. However, the evidence might obscure actual readmission increases. To maintain healthcare quality, hospitals might increase outpatient visits, potentially leading to unintended readmission increases due to operative complications. Hamada et al. reported increased readmission rates following DRG system introduction. Conversely, intensified physician follow-ups in response to earlier discharges might reduce readmissions. Additionally, given that 30-day readmission is a key healthcare quality indicator, hospitals in competitive areas aim to minimize readmissions. Inconsistent readmission rate results may stem from the inclusion of studies across comprehensive medical areas and diverse medical fields. Furthermore, the mechanisms through which hospital payment reform affects patient care quality remain unclear. Further high-quality studies are needed to rigorously monitor and report the association between DRG-based payment and readmissions.

This review found no consistent impact of DRG-based payment on in-hospital mortality, aligning with Brügger and Eichler’s scoping review of international experiences in 2010, which noted minimal changes in death rates with DRG system implementation. However, an OECD countries review linked DRG system introduction to slower quality improvements in surgical and medical adverse event mortality. Despite DRG benefits for quality, this review did not corroborate evidence for DRG-based system effects on in-hospital mortality, possibly due to limited study quality and small sample sizes. Moreover, mortality and readmission rates, while useful for DRG-based payment measurement, are criticized as insufficiently sensitive to healthcare quality. The validity of in-hospital mortality as a quality metric is also questioned, as physicians might discharge terminally ill patients to nursing homes under prospective payment systems. Moreover, merely increasing hospital cost control awareness through DRGs without specific quality-promoting efforts, including healthcare professional training levels and patient-physician interaction time, poses challenges for enhancing medical care quality. Therefore, definitive conclusions about the association between DRG-based payment and in-hospital mortality are difficult. The limited number of eligible mortality analysis studies and the lack of this data in many related reviews highlight the need for more high-quality research before firm conclusions can be drawn.

This study has limitations. First, some studies were excluded due to data unavailability despite extensive database and reference searches. Second, significant heterogeneity was observed, possibly due to variations in DRG system design, treatment settings, and study designs. However, a random-effects model was used to pool results, and subgroup analyses were conducted to explore heterogeneity sources. Third, most eligible studies were before-after studies, and hospital funding reform is rarely an isolated intervention; thus, observed differences might reflect temporal trends independent of DRGs. Finally, the review’s conclusions are contingent on the quantity and quality of current literature, which may evolve. Future high-quality research may refine these conclusions.

Nonetheless, this study contributes by extensively searching electronic databases and including a significant number of studies across diverse DRG-based payment programs. It comprehensively analyzed the impact of DRG-based payment on healthcare quality, including 30-day readmission, in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, and LOS.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that Diagnosis-related group (DRG) based payment positively impacts length of stay but shows no significant effect on inpatient mortality and readmission rates. Current understanding of DRG-payment effects on medical care quality is primarily based on studies with mixed-diagnosis patients. Given the limitations in the quantity and quality of included studies, future research with larger sample sizes and controlled confounding factors is necessary to validate these findings.

Supplemental Material

[Supplemental Material Links]

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to all members of our study team for their dedicated collaboration and to the original authors of the included studies for their valuable work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: [Author contribution details]

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: [Funding source details]

Data Availability: Datasets and materials are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval and consent were not required for this meta-analysis of published studies.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: [ORCID iD link]

Supplemental Material: Available online.