Primary eye care is a cornerstone of community health services, encompassing both clinical services and proactive eye health protection and promotion. For these initiatives to be effective and sustainable, they must be deeply rooted within the community itself, with the eye care sector acting as a supportive partner.

A critical first step in establishing effective primary eye care is conducting a thorough “community diagnosis” through an epidemiological approach. This study allows for the prioritization of community eye problems based on a structured assessment of:

- Magnitude (M): The prevalence and incidence of specific eye conditions, reflecting the number of affected individuals and anticipated new cases.

- Implication (I): The broader social and economic repercussions of these conditions, including healthcare costs, lost productivity, and educational impact.

- Vulnerability (V): The availability and effectiveness of interventions to address these conditions.

- Cost (C): The resources required to implement and sustain control programs.

Prioritization can then be objectively determined using a model that balances these factors:

Priority = (M × I × V) / C

This scientific approach ensures that planning is driven by data and community needs, rather than solely by individual clinical experiences or preferences.

Service Components of Primary Eye Care: A Holistic Approach

Community-based eye care distinguishes itself from hospital-centric models by offering a comprehensive spectrum of services. These services span primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, targeting all community members, regardless of their current eye health status.

Effective primary eye care acknowledges the diverse needs within a community, recognizing three key groups for targeted screening and intervention:

- The Healthy Group: Individuals with no apparent eye problems, requiring preventative education and health promotion.

- The Group with Eye Diseases or Problems: Individuals with existing conditions needing diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing management. This is where differential diagnosis becomes paramount.

- The At-Risk Group: Individuals with predisposing factors for eye diseases, requiring targeted preventative strategies and monitoring.

Therefore, primary eye care extends beyond clinical treatment to encompass a broader public health mandate, addressing the eye health needs of the entire community.

The Clinical Service Component: Differential Diagnosis at the Forefront

Community diagnosis serves as the foundation for all primary eye care activities, often revealing unique eye health landscapes within different communities. This understanding necessitates adaptable clinical service components that are tailored to the specific social, economic, and healthcare contexts of each community. The “essential elements” of primary eye care are thus not universally fixed but rather community-specific, extending beyond major blinding conditions to include common, yet impactful, eye disorders.

Decisions regarding service provision must be guided by public health principles, prioritizing conditions that are both preventable and manageable at the primary care level, and are prevalent within the community. This might include addressing reading difficulties in the elderly or managing seasonal conjunctivitis, alongside more sight-threatening conditions. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides essential guidelines to inform the scope of primary eye care services.

WHO Guidelines for Primary Eye Care and Differential Diagnosis

The WHO guidelines categorize eye conditions based on the level of primary health care worker training and the appropriate management strategy, inherently emphasizing the need for differential diagnosis at each level:

-

Conditions to be Recognized and Treated by a Trained Primary Health Care Worker: These are typically common and easily manageable conditions where primary health workers can be trained to confidently make a differential diagnosis and initiate treatment.

- Conjunctivitis and Lid Infections:

- Acute Conjunctivitis: Differentiating between viral, bacterial, and allergic conjunctivitis is key to appropriate management.

- Ophthalmia Neonatorum: Requires urgent differential diagnosis to distinguish between gonococcal and chlamydial infections, and prompt treatment to prevent blindness.

- Trachoma: Differential diagnosis from other causes of follicular conjunctivitis is crucial for targeted public health interventions.

- Allergic and Irritative Conjunctivitis: Identifying and differentiating triggers from infectious causes is essential for effective relief.

- Lid Lesions (Stye and Chalazion): While often straightforward, differential diagnosis from more serious lid conditions may be necessary.

- Trauma:

- Subconjunctival Hemorrhages: Usually benign but differential diagnosis should rule out more serious underlying causes, especially with recurrent cases.

- Superficial Foreign Body: Requires careful examination and removal, ensuring differential diagnosis from penetrating injuries.

- Blunt Trauma: Initial assessment and differential diagnosis to identify potential for more severe internal eye damage.

- Blinding Malnutrition: Recognizing and addressing nutritional deficiencies that can lead to ocular complications requires understanding the differential diagnosis of nutritional blindness.

- Conjunctivitis and Lid Infections:

-

Conditions to be Recognized and Referred After Treatment Initiation: These conditions require prompt referral to specialized care, but primary health workers can initiate crucial first-line treatments after making a preliminary differential diagnosis.

- Corneal Ulcers: Differential diagnosis of infectious vs. non-infectious ulcers is important for guiding initial antimicrobial therapy before referral.

- Lacerating or Perforating Injuries of the Eyeball: Immediate referral is paramount, but initial assessment involves differential diagnosis to understand the extent of injury.

- Lid Lacerations: Requires referral for surgical repair, but primary care can provide initial wound care and differential diagnosis of associated injuries.

- Entropion/Trichiasis: Referral for surgical correction is needed, but primary care can offer temporary relief and differential diagnosis from other causes of eye irritation.

- Burns (Chemical, Thermal): Urgent referral is necessary, but initial management involves irrigation and differential diagnosis of burn severity.

-

Conditions that Should be Recognized and Referred for Treatment: These conditions necessitate specialist care for definitive differential diagnosis and management.

- Painful Red Eye with Visual Loss: This is a red flag symptom requiring urgent referral for differential diagnosis of conditions like acute glaucoma, uveitis, or corneal pathology.

- Cataract: While common, differential diagnosis of cataract type and associated conditions is important for surgical planning and patient counseling.

- Pterygium: Referral is needed if symptomatic or encroaching on vision, requiring differential diagnosis from other conjunctival growths.

- Visual Loss: A broad symptom requiring thorough investigation and differential diagnosis to identify the underlying cause, ranging from refractive errors to retinal diseases.

Based on WHO guidelines and epidemiological data, countries like Thailand and Myanmar, starting primary eye care in 1981, integrated conditions like cataract, trachoma, eye injuries, corneal ulcers, glaucoma, ophthalmia neonatorum, eye infections, pterygium, refractive errors, and conditions with low visual acuity into their primary health care models. These conditions, prevalent in the region, became essential elements of clinical primary eye care services. Similar needs were identified in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and even China, highlighting regional commonalities.

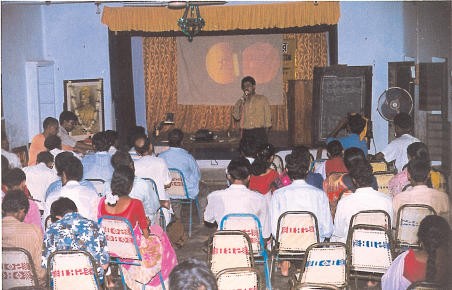

Discussion on common eye diseases for community volunteers, utilizing ICEH slide sets for training. Vivekananda Mission Asram, West Bengal, India.

However, the specific needs of primary eye care can vary significantly across regions. For example, in areas with high onchocerciasis prevalence, targeted interventions for this condition become a critical component of primary eye care.

Integration Matrix: Embedding Primary Eye Care within Primary Health Care

Primary eye care should never be a standalone initiative but rather an integrated component of broader primary health care systems. It serves as a crucial entry point to engage communities with comprehensive health services. Effective integration requires a thorough situational analysis of the community, focusing on the essential elements of primary health care and how eye care services can be seamlessly incorporated.

Cultural evening promoting health care awareness in India.

The integration matrix below illustrates how primary eye care can be interwoven with various aspects of primary health care, assuming a foundational health care system is in place.

Table 1. Primary Eye Care Integration Matrix

| PHC PEC | Health education | Family planning & MCH | Food & nutrition | Safe Water & basic sanitation | Extended programme of immunisation (**) | Essential drugs | Control of local endemic diseases (****) | Care for mild ailments (‘simple’ treatment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cataract Surgical Non-surgical | +++ ++ | + for congenital cataract | NA | NA | NA | ++ post operation care | +++ case finding, referral & community care | +++ case finding, referral & community care |

| Trachoma Active Complications | +++ ++ | +++ | +++ ++ | NA | +++ tetracycline ointment | trachoma programme +++ +++ | trachoma programme +++ +++ | |

| Glaucoma Acute attack Angle-closed(*) | ++ ++ | + for congenital glaucoma | NA | NA | NA | ++ pilocarpine eye drops | ++ pilocarpine eye drops | |

| Eye injuries | ++ | +++ accident prevention | ++ improve environment | NA | +++ tetracycline ointment | +++ tetracycline ointment | ||

| Corneal ulcer | +++ | +++ accident prevention | NA | NA | measles immunisation | +++ tetracycline ointment | +++ tetracycline ointment | |

| Eye infections EKG Chronic | ++ ++ | +++ ++ | NA | ++ ++ | NA | +++ ++ | disaster management sometimes | +++ tetracycline ointment |

| Ophthalmia neonatorum | +++ | +++ | NA | +++ | +++ immediate referral | |||

| Pterygium Surgical Non-surgical | ++ + | NA | NA | ++ ++ | NA | ++ referral | ||

| Refractive error & Reading difficulties | ++ | ++ family screening | NA | NA | NA | + providing simple spectacles | + providing simple spectacles | |

| VA less than 0.05 ( | ++ | ++ family screening | NA | NA | NA | ++ referral |

(*) In many instances, angle-closure glaucoma refers to the acute attack, with one eye already blind and prophylaxis required for the second eye. Secondary glaucoma is common among neglected age-related cataract patients.

(**) EPI staff are good health communicators, educators and gather community information.

(***) Diabetic retinopathy is common in some communities. This is the category 4 in the WHO categories of visual impairment.

(****) The cataract backlog might be regarded as an endemic disease in the given region, like tuberculosis, malaria and leprosy, etc. Trachoma, and its control is also relevant here. When the conditions are welt controlled, they become part of a successful integrated health programme in that locality.

Cataract Programs as a Model for Primary Eye Care Integration

Cataract programs serve as a powerful example of how primary eye care can function effectively within the primary health care framework. The success of these programs in numerous countries hinges on robust community involvement, particularly in case finding and referral. Surgical eye teams can then operate efficiently and cost-effectively, provided community-level preparations are well-organized prior to surgical interventions.

Cataract program activities typically begin with brief training sessions for community health workers on cataract recognition. This is followed by proactive door-to-door visits for case finding. Multi-stage screening is integral to primary eye care in identifying cases and encouraging patients to seek surgical treatment. Simultaneously, comprehensive eye care information should be disseminated throughout the community using diverse communication channels. Table 2 summarizes potential community-level activities within a cataract program.

Table 2. Cataract Program at Community Level

| Level | Individual | Family | Community | 1st level of contact (Health Centre) | 1st level of referral (District Hospital) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Action | Aware of own vision. Slowly progressing, painless visual impairment, either one or both eyes. Respond to health workers after screening. Prompt report to eye team for operation. | Help bringing the cataract patient to eye unit. Encourage operation and prepare hospitalisation. Adequate postoperative care and suitable home and out-door activites. | Co-operate with health workers and visiting eye personnel in surgical care. Surgical subsidies for the poor. | Co-operate with visiting eye team in community activities. Co-ordinate community in the cataract programmes. | Co-operate with visiting eye team and preparation of service sites. Post-operative follow-up. Proper care for complicated cases. |

| Input | Health education, posters, booklets, etc. | Health education, posters, booklets, etc. | Primary eye care course. Primary eye care kits, manual and guidelines, records and reporting systems. | Primary eye care course, minimum supplies and equipment, records and reporting systems. | Short, clinical training, minimum required supplies and equipment. Monitoring/supervision. |

Footnotes

(*) Highly prevalent in Thailand

(**) Implies possible cases with disorders of the posterior segment of the eye, which may need referral.