Have you ever observed how seamlessly nurses transition between patients, instantly grasping their needs and delivering tailored care? This proficiency stems from a systematic approach: the nursing process. It’s the essential framework that empowers nurses to provide structured, patient-centered care, ensuring safety and promoting well-being. This article will delve into the nursing process, with a specific focus on nursing care plans, documentation, nursing diagnoses, and collaborative problem-solving, highlighting their critical role in contemporary nursing practice.

Understanding the Foundations: Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning in Nursing

Before exploring the nursing process in detail, it’s crucial to understand the cognitive skills that underpin effective nursing practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking in nursing extends beyond simply following protocols. It’s a multifaceted process that involves analyzing clinical scenarios, considering teamwork dynamics, fostering collaboration, and optimizing workflow efficiency.[^1] A critical thinker in nursing proactively validates patient information, bases care plans on individual needs and current best practices, and prioritizes patient safety above rote task completion.

Key attitudes of critical thinkers include:

- Independent Thinking: Formulating your own judgments and not blindly accepting information.

- Fair-mindedness: Approaching all perspectives with impartiality and without prejudice.

- Insight into Self-centeredness: Recognizing and mitigating personal biases and considering the broader good in patient care decisions (sociocentricity vs. egocentricity).

- Intellectual Humility: Acknowledging the limits of one’s knowledge and being open to learning.

- Non-judgmental Approach: Applying professional ethics rather than personal moral standards in decision-making.

- Integrity: Maintaining honesty and strong ethical principles in all nursing actions.

- Perseverance: Remaining persistent in providing optimal care, even when faced with challenges.

- Confidence: Believing in your ability to deliver competent and safe care.

- Openness to Explore Feelings and Thoughts: Willingness to consider diverse perspectives and methods of understanding patient needs.

- Curiosity: Continuously questioning “why” and seeking deeper understanding of patient conditions and care strategies.

Clinical reasoning, closely linked to critical thinking, is defined as “a complex cognitive process that employs both formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient data, evaluate its significance, and consider various courses of action.”[^2] Effective clinical reasoning allows nurses to generate potential solutions, weigh evidence, and select the most appropriate interventions for each patient. This skill develops with experience and a strong foundation of nursing knowledge.[^3]

The Power of Inductive and Deductive Reasoning in Clinical Judgment

Inductive and deductive reasoning are essential components of critical thinking that directly inform clinical judgment within the nursing process.

Inductive reasoning is about moving from specific observations to broader generalizations. It involves noticing cues – deviations from expected patient findings that signal potential issues. Nurses gather these cues, identify patterns, and form generalizations. This is akin to piecing together clues to understand a larger clinical picture. From these generalizations, nurses develop hypotheses about the patient’s problems – proposed explanations for the situation. Identifying the “why” behind a patient’s condition is crucial for developing effective solutions.

Paying meticulous attention to patient details, their environment, and interactions is fundamental to inductive reasoning. Nurses, like detectives, must be observant, utilizing their senses to gather cues.

Figure 4.1

Inductive Reasoning: Observing Cues for Clinical Insights

Example of Inductive Reasoning: A nurse observes redness, warmth, and tenderness at a surgical incision site. Recognizing these cues as a pattern indicative of infection, the nurse hypothesizes a surgical site infection. This leads to communication with the provider and subsequent orders for antibiotics.

Deductive reasoning, conversely, is “top-down thinking.” It applies general rules or standards to specific situations. Nurses utilize established guidelines from Nurse Practice Acts, regulatory bodies, professional organizations like the American Nurses Association, and institutional policies to guide patient care decisions and problem-solving.

Example of Deductive Reasoning: A hospital policy promoting quiet zones at night, based on research showing improved patient recovery with rest, exemplifies deductive reasoning. Nurses implement this policy by minimizing noise and light at night for all patients, regardless of their individual sleep patterns.

Clinical judgment, the outcome of critical thinking and clinical reasoning, is defined by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) as “the observable outcome of critical thinking and decision-making, utilizing nursing knowledge to assess situations, identify prioritized concerns, and generate evidence-based solutions for safe patient care.”^4 It’s the cornerstone of safe and effective nursing practice, assessed by the NCLEX licensure exam.

Evidence-based practice (EBP), as defined by the ANA, is integral to clinical judgment. EBP involves “integrating the best evidence from research, clinical expertise, patient preferences, and available resources into decision-making.”[^5] It ensures that nursing care is informed by the most current and reliable knowledge.

The Nursing Process: A Systematic Approach to Patient-Centered Care

The nursing process is a systematic, patient-centered, critical thinking model. It provides a roadmap for nurses to deliver holistic and individualized care. Rooted in the American Nurses Association (ANA) Standards of Professional Nursing Practice, the nursing process is represented by the mnemonic ADOPIE: Assessment, Diagnosis, Outcomes Identification, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.

This process is dynamic and cyclical, constantly adapting to the patient’s evolving health status.

Figure 4.3

The Cyclical Nursing Process: ADOPIE

Patient Scenario A: Illustrating the Nursing Process[^6]

Consider a patient prescribed Lasix 80mg IV daily for heart failure. During morning assessment, the nurse notes a blood pressure of 98/60, heart rate of 100, and reports of lightheadedness and dry mouth. Reviewing the patient’s baseline vital signs, the nurse observes a significant drop in blood pressure. Assessment: The nurse collects data (vital signs, patient reports, weight decrease). Diagnosis: Analyzing cues, the nurse formulates a nursing diagnosis of Fluid Volume Deficit. Outcomes Identification: The nurse sets goals for restoring fluid balance. Planning: The nurse decides to withhold Lasix and contact the provider. Implementation: The nurse contacts the provider, promotes oral fluid intake, and monitors hydration status. Evaluation: By the end of the shift, the patient’s fluid balance is restored.

In this scenario, the nurse’s clinical judgment, guided by the nursing process, prevents potential harm by questioning the medication order based on patient assessment.

Let’s examine each component of the nursing process in detail:

1. Assessment: Gathering Comprehensive Patient Data

The Assessment phase, the first Standard of Practice, involves the “registered nurse collecting comprehensive data relevant to the healthcare consumer’s health and/or situation.”[^7] This goes beyond physical data to include psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle factors. For instance, assessing a patient in pain includes understanding their emotional response, coping mechanisms, and impact on daily life.[^8]

Subjective Data: This is information gathered directly from the patient and/or family, reflecting their perspective. Documented subjective data is crucial for understanding the patient’s experience. It’s essential to build rapport to gain accurate subjective data. Primary data comes directly from the patient, while secondary data is obtained from family, medical records, or other sources.

Example: “The patient reports their pain is a 2 out of 10,” is an example of subjective data.

Objective Data: This is observable and measurable data obtained through senses – sight, sound, touch, smell. It is reproducible and verifiable by another observer. Examples include vital signs, physical exam findings, and lab results.

Example: “Radial pulse is 58 and regular; skin is warm and dry,” is objective data.

Sources of Assessment Data:

- Interview: Engaging the patient in conversation, active listening, and observing verbal and nonverbal cues. Reviewing the patient chart beforehand helps focus the interview.

- Physical Examination: A systematic hands-on assessment using techniques like inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. This includes vital sign measurement. RNs conduct initial and ongoing assessments, while certain tasks can be delegated to LPNs/LVNs or UAPs.

- Review of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests: Analyzing results to understand the patient’s health status and inform care decisions. Nurses must verify the appropriateness of prescriptions based on these results.

Types of Assessments:

- Primary Survey: Rapid assessment of consciousness, airway, breathing, and circulation in emergency situations.

- Admission Assessment: Comprehensive initial assessment upon admission to a healthcare facility.

- Ongoing Assessment: Regular, often shift-based, head-to-toe assessments in acute care settings.

- Focused Assessment: In-depth assessment of a specific problem or condition.

- Time-lapsed Reassessment: Periodic assessments in long-term care to evaluate progress over time. [^9]

Scenario C: Putting Assessment into Practice[^10]

Consider Ms. J., a 74-year-old admitted with shortness of breath, ankle swelling, and fatigue. Her history includes hypertension, heart failure, and diabetes. Admission vital signs: BP 162/96, HR 88, SpO2 91% on room air, RR 28, Temp 97.8°F. Weight is up 10 lbs in 3 weeks. She reports, “I’m so short of breath,” and “My ankles are so swollen.” Physical exam reveals lung crackles and 2+ pitting edema. Potassium is 3.4 mEq/L. Her daughter expresses concern about Ms. J. living alone.

- Subjective Data: Patient reports of shortness of breath, swollen ankles, fatigue, dizziness, desire to learn about health. Daughter’s worry.

- Objective Data: Vital signs (elevated BP, RR, HR; low SpO2), weight gain, lung crackles, edema, low potassium.

- Secondary Data: Daughter’s statement, medical history.

2. Diagnosis: Formulating Nursing Diagnoses and Collaborative Problems

The Diagnosis phase, the second Standard of Practice, involves “analyzing assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[^11] The RN prioritizes diagnoses to guide care planning, documenting them to facilitate outcome development and collaborative planning.

Analyzing Assessment Data: Nurses analyze collected data to identify deviations from expected norms and determine clinically relevant cues.

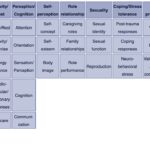

Clustering Information: Relevant cues are grouped into patterns using frameworks like Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns. This helps identify generalizations and potential nursing diagnoses.

Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns:[^12]

- Health Perception-Health Management

- Nutritional-Metabolic

- Elimination

- Activity-Exercise

- Sleep-Rest

- Cognitive-Perceptual

- Self-perception and Self-concept

- Role-Relationship

- Sexuality-Reproductive

- Coping-Stress Tolerance

- Value-Belief

Identifying Nursing Diagnoses: A nursing diagnosis is a “clinical judgment about a human response to health conditions/life processes.”[^13] It’s distinct from a medical diagnosis and focuses on the patient’s experience of health issues. Nurses use resources like NANDA International (NANDA-I) to select standardized nursing diagnoses. NANDA-I provides a comprehensive list of diagnoses, regularly updated based on research.

Nursing Diagnoses vs. Medical Diagnoses: Medical diagnoses focus on diseases; nursing diagnoses focus on patient responses to health problems. Patients with the same medical diagnosis can have different nursing diagnoses based on their unique responses. Nursing diagnoses are the foundation for individualized care plans.

Example: Ms. J.’s medical diagnosis is heart failure. Her nursing diagnosis relates to her response to heart failure, such as Fluid Volume Excess.

Types of Nursing Diagnoses:

- Problem-Focused: Describes an existing undesirable human response. Requires related factors (causes) and defining characteristics (signs/symptoms).

- Health Promotion-Wellness: Focuses on a patient’s desire to improve well-being. Used when a patient is ready to enhance specific health behaviors.

- Risk: Describes vulnerability to developing a negative human response. Supported by risk factors.

- Syndrome: A cluster of nursing diagnoses that frequently occur together and are best addressed collectively.

Establishing Nursing Diagnosis Statements: NANDA-I recommends a statement structure including the nursing diagnosis, related factors, and defining characteristics. This is often referred to as PES format (Problem, Etiology, Signs/Symptoms), although NANDA-I terminology has evolved.

- Problem (P): The nursing diagnosis itself.

- Etiology (E): Related factors, the “cause” of the diagnosis (phrased as “related to”).

- Signs and Symptoms (S): Defining characteristics, the evidence supporting the diagnosis (phrased as “as manifested by” or “as evidenced by”).

Examples of Nursing Diagnosis Statements for Ms. J.:

- Problem-Focused: Fluid Volume Excess related to excessive fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles, 2+ pitting edema, 10-pound weight gain, and patient report of “My ankles are so swollen.”

- Health Promotion: Readiness for Enhanced Health Management as manifested by expressed desire to “learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

- Risk: Risk for Falls as evidenced by dizziness and decreased lower extremity strength.

- Syndrome: Risk for Frail Elderly Syndrome related to activity intolerance, social isolation, and fear of falling.

Prioritization of Nursing Diagnoses: After identifying diagnoses, prioritize them based on patient needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation) are common prioritization frameworks. Acute problems often take precedence over chronic ones, and actual problems over potential risks (though risk diagnoses can be high priority).

Example: For Ms. J., Fluid Volume Excess and Risk for Falls are high priority due to physiological needs and safety concerns.

Figure 4.7

Prioritization in Nursing Care: Key Considerations

3. Outcome Identification: Setting SMART Goals

Outcome Identification, the third Standard of Practice, involves the “registered nurse identifying expected outcomes for an individualized plan.”[^14] Outcomes are measurable, patient-centered goals, developed collaboratively with the patient and healthcare team, reflecting patient values and culture. They are documented with a timeframe for achievement.

Outcomes are “measurable behaviors demonstrated by the patient in response to nursing interventions.”[^15] They guide care planning and evaluation. Outcome identification involves setting both short- and long-term goals and creating specific expected outcome statements for each nursing diagnosis.

Goals are broad statements of desired change, either short-term or long-term, depending on the care setting. A nursing goal is the desired direction of patient progress to address the nursing diagnosis.

Example: For Ms. J.’s Fluid Volume Excess, a broad goal is: “Ms. J. will achieve fluid balance.”

Expected Outcomes are specific, measurable, and time-bound. Nurses may use resources like the Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC), a standardized system of nursing outcomes linked to NANDA-I diagnoses.

SMART Criteria for Outcome Statements:[^16]

- Specific: Clearly defines what needs to be achieved.

- Measurable: Uses quantifiable parameters for assessment.

- Attainable/Action-oriented: Realistic and patient-driven, using action verbs.

- Relevant/Realistic: Considers patient’s condition, values, and resources.

- Time-bound: Includes a specific timeframe for evaluation.

Figure 4.9

SMART Outcome Statements: A Guide

Example of a SMART Outcome for Ms. J.: “The patient will have clear bilateral lung sounds within the next 24 hours.”

4. Planning: Developing Nursing Care Plans and Collaborative Strategies

Planning, the fourth Standard of Practice, involves the “registered nurse developing a collaborative plan to achieve expected outcomes.”[^17] This includes selecting evidence-based nursing interventions tailored to the patient. The care plan is documented to ensure consistent care across the healthcare team.

Nursing Interventions are evidence-based actions nurses take to achieve patient outcomes. They should address the related factors of the nursing diagnosis. Resources like the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) system provide standardized, evidence-based interventions.

Types of Nursing Interventions:

- Direct Care: Interventions involving direct patient contact (e.g., wound care, repositioning).

- Indirect Care: Actions performed away from the patient but supporting their care (e.g., care conferences, documentation).

- Independent Interventions: Actions nurses can initiate without a provider order (e.g., patient education, repositioning for edema).

- Dependent Interventions: Require a provider’s prescription (e.g., medication administration).

- Collaborative Interventions: Implemented in collaboration with other healthcare team members (e.g., respiratory therapy, physical therapy).

Figure 4.12

Collaborative Care Planning: Teamwork in Nursing

Example Interventions for Ms. J.’s Fluid Volume Excess:

- Independent: “Reposition patient every 2 hours to promote fluid redistribution in dependent edema areas.”

- Dependent: “Administer prescribed diuretic medication as scheduled.”

- Collaborative: “Consult with respiratory therapy for management of decreased oxygen saturation if needed.”

Nursing Care Plans: These are documented plans that outline the nursing process for individual patients. They are legally required in many healthcare settings to ensure quality and continuity of care. Care plans should be individualized and may be standardized templates customized for each patient.

Figure 4.13

Standardized Nursing Care Plan Example

5. Implementation: Putting the Plan into Action

Implementation, the fifth Standard of Practice, is when the “registered nurse implements the identified plan.”[^18] This involves prioritizing interventions, ensuring patient safety, delegating appropriately, and documenting actions. Continuous reassessment is crucial during implementation to adapt the plan as needed.

Prioritizing Implementation: Use Maslow’s Hierarchy and ABCs to prioritize interventions. Less invasive actions are generally preferred initially. Consider the urgency and potential impact of delayed interventions.

Patient Safety during Implementation: Patient safety is paramount. Nurses must critically evaluate if planned interventions remain safe given the patient’s current condition. Preventing errors is a core nursing responsibility. Quality improvement initiatives are essential to enhance patient safety and reduce medical errors, as highlighted by reports like “To Err Is Human” and “Preventing Medication Errors.”

Delegation of Interventions: RNs may delegate tasks to LPNs/LVNs or UAPs, while retaining accountability. Delegation must be appropriate based on patient condition, task complexity, and the delegate’s competence. RNs must be aware of Nurse Practice Acts and agency policies regarding delegation.

Documentation of Interventions: Timely and accurate documentation of interventions in the patient’s Electronic Medical Record (EMR) is crucial for communication and legal accountability. If it’s not documented, it’s considered not done.

Coordination of Care and Health Teaching/Promotion: Implementation also includes coordinating care with the interprofessional team and providing patient education. Patient teaching is an ongoing intervention in every patient encounter.

Example Implementation for Ms. J.: Administer diuretic first (priority intervention), monitor lung sounds, delegate daily weight to CNA, educate patient on medications and edema management, and document all interventions in the EMR.

6. Evaluation: Assessing Progress and Refining the Care Plan

Evaluation, the sixth Standard of Practice, is when the “registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[^19] This involves continuously assessing patient status and the effectiveness of the care plan.

Evaluating Outcome Achievement: Nurses analyze reassessment data to determine if expected outcomes were met, partially met, or not met within the specified timeframes. If outcomes are not met, the care plan must be revised.

Revising the Care Plan: Evaluation prompts reflection and potential revisions. Questions to guide revision include:

- Were there any unexpected events?

- Has the patient’s condition changed?

- Were outcomes and timeframes realistic?

- Are diagnoses still accurate?

- Are interventions effectively targeted?

- What barriers were encountered?

- Does ongoing assessment suggest changes to diagnoses, outcomes, interventions, or implementation?

- Are different interventions needed?

Example Evaluation for Ms. J.:

For Fluid Volume Excess, outcomes were “Partially Met” as dyspnea and lung crackles improved, but edema persisted. The care plan was revised to include TED hose and leg elevation. Risk for Falls outcome was “Met” as the patient understood fall precautions and remained fall-free. Evaluation findings are documented in the patient record.

Conclusion: The Nursing Process as a Dynamic Framework for Excellence

The nursing process, encompassing Assessment, Diagnosis, Outcomes Identification, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADOPIE), is a dynamic and essential framework for delivering patient-centered, safe, and effective nursing care. It emphasizes critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and collaborative problem-solving, ensuring individualized care plans that address patient needs and promote positive outcomes. Mastery of nursing care plans, documentation, nursing diagnoses, and collaborative strategies within this framework is fundamental to professional nursing practice.

Video Review of Creating a Sample Care Plan[^20]

References

[^1]: Klenke-Borgmann L., Cantrell M. A., Mariani B. Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2020;41(4):215–221.

[^2]: Klenke-Borgmann L., Cantrell M. A., Mariani B. Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2020;41(4):215–221.

[^3]: Powers, L., Pagel, J., & Herron, E. (2020). Nurse preceptors and new graduate success. American Nurse Journal, 15(7), 37-39.

[^5]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^6]: “Patient Image in LTC.JPG” by ARISE project is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[^7]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^8]: American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/

[^9]: Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company.

[^10]: “grandmother-1546855_960_720.jpg” by vendie4u is licensed under CC0

[^11]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^12]: Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company.

[^13]: Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York.

[^14]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^15]: Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York.

[^16]: Campbell, J. (2020). SMART criteria. Salem Press Encyclopedia.

[^17]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^18]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^19]: American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

[^20]: RegisteredNurseRN. (2015, June11). Nursing care plan tutorial | How to complete a care plan in nursing school. [Video]. YouTube.

Figure 4.5

Building Rapport: Obtaining Subjective Data Through a Caring Nurse-Patient Relationship