Dementia, a syndrome characterized by a decline in cognitive function, poses significant challenges for individuals and their families. Beyond memory loss, dementia encompasses a spectrum of unmet palliative care needs, including behavioral disturbances, pain management, complex decision-making regarding treatment and care settings, and substantial caregiver burden.1–9 While hospice care has demonstrated benefits for dementia patients and their families at the end of life,10,11 historically, access to palliative care, especially earlier in the disease trajectory, has been limited.

Research from 1995 indicated that only a small fraction of hospice programs actively admitted patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia.12 Referral rates to hospice for dementia patients in nursing homes and home care settings remained low, ranging from 6% to 22%.9,13 These low figures highlight significant barriers hindering the provision of palliative care to this vulnerable population.

One major obstacle is the misperception of dementia as a non-terminal condition.14 This is despite increasing evidence demonstrating dementia as a leading cause of death.9 The cognitive and communication impairments inherent in dementia further complicate symptom recognition and management.8 Caregiving for individuals with dementia is often prolonged and intensely demanding, marked by unique patterns of anticipatory grief and bereavement that differ from other terminal illnesses.14–16 Furthermore, the traditional hospice model, primarily designed for cancer patients with predictable decline, struggles to accommodate the protracted and fluctuating disease course of dementia.14,17 Existing hospice eligibility criteria for dementia have also been criticized for their inaccuracy in predicting mortality and their rigid application, which often fails to capture the complex realities of dementia progression.18 These factors collectively contribute to difficulties in prognostication, a crucial requirement for Medicare hospice benefits.12,19,20

Figure 1

Figure 1

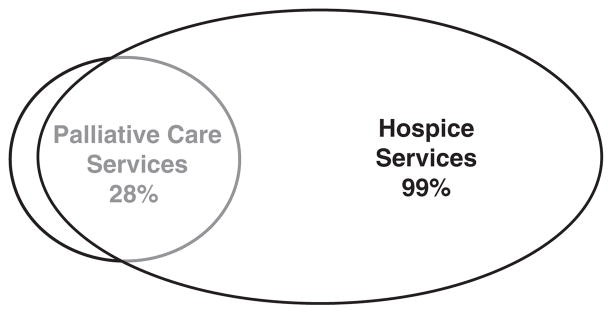

Figure 1: Weighted proportion of programs offering palliative care or hospice services, illustrating the prevalence of hospice services compared to palliative care services outside of hospice benefit.

Despite these challenges, there has been a positive shift. The proportion of hospice patients with a primary dementia diagnosis has risen from 6.8% in 2001 to 11.1% in 2008,21,22 indicating increasing recognition of dementia as a condition requiring end-of-life care. Simultaneously, palliative care programs outside of hospice have expanded, offering another avenue for supporting dementia patients who may not yet meet hospice criteria but have substantial palliative needs.23,24 This expansion of non-hospice palliative care presents a crucial opportunity to address the unmet needs of dementia patients earlier in their illness trajectory.25,26 However, even within non-hospice palliative care settings, challenges related to prognostication, communication, and disease-specific complexities persist.27 Understanding the current landscape of palliative care provision for dementia and identifying remaining barriers is essential for improving care delivery.

This study aimed to assess the extent to which hospice and non-hospice palliative care programs serve patients with dementia. It further sought to identify the barriers and facilitators encountered by program administrators in providing non-hospice palliative care for dementia patients, from initial diagnosis through the bereavement period for families.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

This research employed a two-phase survey design, approved by the Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI)/Clarian institutional review board. The study population was drawn from the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) program list, a comprehensive database of hospice and palliative care organizations in the United States. The NHPCO database is regularly updated to include all Medicare-certified hospice providers and known non-certified hospice providers.

The NHPCO list was categorized into three strata: organizations providing hospice care only (Stratum 1), programs offering both hospice and non-hospice palliative care (Stratum 2), and programs providing non-hospice palliative care exclusively (Stratum 3). To ensure adequate representation of non-hospice palliative care programs, stratified sampling was used to oversample programs in Strata 2 and 3. A random sample of 800 programs was initially selected, aiming for 100 responses to a detailed web-based survey focusing on non-hospice palliative care. After removing duplicates, the final sample size was 796 programs.

Data Collection Instruments

Data collection involved two survey instruments: a brief telephone survey followed by a more in-depth online survey. The telephone survey was administered to executive directors or senior administrators of sampled programs, considered the most knowledgeable individuals regarding patient populations and program operations. Eligibility criteria included programs providing palliative or hospice care to adults.

The telephone survey screened programs for provision of palliative care and hospice services to patients with dementia within the past year. Specific questions included: “Within the past year, has your program provided palliative care to any patient with a primary diagnosis of dementia?” and a similar question for hospice services. Additional questions gathered information on program characteristics such as size, setting (inpatient/outpatient), location (urban/suburban/rural), and affiliations with other healthcare organizations.

Respondents indicating provision of non-hospice palliative care in the telephone survey were invited to participate in a subsequent web-based survey. This survey delved into four key areas: perceived barriers to providing palliative care for dementia patients, palliative care needs of this population, opinions on palliative care in dementia, and detailed program information (program age, funding sources, staff composition). The web-based survey utilized a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions.

Both survey instruments were developed by the research team and pilot-tested with national palliative care experts and local hospice administrators. Feedback from pilot testing led to revisions for clarity and content validity. Cognitive interviewing with five programs from the selected sample further refined the surveys. The telephone survey was programmed into Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview software, and the web-based survey was developed and tested across different web browsers.

Survey Administration Procedures

In July 2008, introductory letters explaining the study’s purpose, sponsoring organizations (including the Alzheimer’s Association), and mailing list source (NHPCO) were mailed to executive directors. Participants were given contact information and the option to opt out of further participation.

Telephone surveys commenced in August 2008, conducted by trained interviewers following a standardized script. Interviewers attempted to reach the executive director or a designated senior administrator. Up to 15 call attempts were made per program, with messages left after the 8th and 15th attempts. Non-responding programs received a follow-up letter from the principal investigator reiterating the study’s importance. Quality control procedures were implemented by the Survey Research Center at IUPUI.

Respondents who agreed to participate in the web-based survey received an email link upon completion of the telephone survey. Email reminders with the survey link were sent at 2 days, 1 week, 2 months, and before data collection closure. Reminder letters and phone calls were also used to maximize response rates.

Data Analysis

Telephone survey data were analyzed to estimate program characteristics for the entire NHPCO population, as well as for programs providing palliative care and hospice services separately. Weighted averages were calculated to account for stratified sampling. Web-based survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression to identify predictors of providing palliative care to dementia patients. Attitudes, barriers, and successful strategies were also analyzed descriptively.

Qualitative data from open-ended survey questions were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.28,29 Two investigators independently coded responses related to barriers, successful strategies, and palliative care needs. Categories and themes were identified through iterative discussions and consensus-building within the research team. Frequencies of themes were then compiled.

RESULTS

Telephone Survey Response and Program Characteristics

Out of 797 initially sampled programs, 84 were deemed ineligible due to invalid contact information and 6 because they did not serve a general adult population. Of the 713 eligible programs, 426 completed the telephone survey, yielding a 60% response rate. Responders and non-responders did not differ geographically. Executive directors participated in 96% of surveys. Among respondents, 173 provided both palliative care and hospice, 240 provided hospice only, and 13 provided palliative care only.

Table 2 details the estimated program characteristics for all respondents. It was estimated that 28% of NHPCO-listed programs offered non-hospice palliative care, and 99% provided hospice care. Program characteristics such as for-profit status and freestanding status differed slightly from national hospice averages, potentially reflecting the sampling frame.

Dementia Care Provision

Among programs offering non-hospice palliative care, 72% had served at least one patient with a primary dementia diagnosis in the past year. No significant program characteristic differences were found between palliative care programs serving dementia patients and those that did not. A striking 94% of hospice programs had provided care to dementia patients in the same timeframe. Hospice programs were more likely to have served dementia patients if they were larger, affiliated with nursing homes, or located in suburban areas.

Palliative care and hospice services were equally prevalent in rural versus urban/suburban settings and among for-profit and faith-based programs. Palliative care services were less common than hospice in assisted living and nursing homes.

Online Survey Response and Program Demographics

Eighty out of 186 eligible palliative care programs responded to the online survey (43% response rate). Responders and non-responders were similar in program affiliation, for-profit status, and dementia care provision, but responders were less likely to be in rural areas. Of responders, 93% were hospice-affiliated, and 80% provided palliative care to dementia patients. The majority (36%) had operated for over 6 years. Funding sources included Medicare (63%), Medicaid (54%), commercial insurance (56%), and philanthropy (50%). Team members commonly included nurses (94%), social workers (83%), physicians (74%), and chaplains (59%). Among palliative care programs also offering hospice, 92% reported dementia patients transitioning out of hospice before death.

Barriers to Palliative Care for Dementia

Table 3 summarizes the perceived barriers to providing palliative care for dementia patients. The highest-rated barriers included reimbursement challenges (58% rated as extremely important), lack of family and provider awareness of palliative care for dementia (54% and 50%, respectively), need for respite services (46%), and lack of available family caregivers (47%).

Qualitative responses echoed these themes, emphasizing caregiver stress and reimbursement difficulties when patients did not meet hospice criteria or require skilled nursing. Lack of awareness led to low and late referrals, with prognosis determination cited as another significant barrier.

Lower-rated barriers included lack of expertise in managing behavioral symptoms (12% extremely important), staff training (10%), and relationships with dementia-focused organizations (13%). No significant differences in barrier ratings were found between programs that did and did not serve dementia patients.

Palliative Care Needs of Dementia Patients

Table 4 outlines the perceived palliative care needs and services for dementia patients. Respondents overwhelmingly rated all listed needs as very or extremely important (over 75%). The most highly prioritized needs were family information on disease progression (83% extremely important), behavioral symptom management (83%), and addressing caregiver burden and guilt (78%). Open-ended responses highlighted an additional key need: patient care beyond symptom management, including nurse aides, general medical services, and care coordination. Caregiver support and symptom management (confusion, agitation, pain) were consistently emphasized.

Successful Strategies in Palliative Care for Dementia

Table 1 presents successful strategies identified by programs providing palliative care for dementia. The most frequent theme centered on program staff, particularly the interdisciplinary team and family-centered approaches. Collaboration with community organizations (support groups, nursing homes) and comprehensive patient/family services were also prominent.

Attitudes Toward Palliative Care in Dementia

Table 5 displays attitudes toward palliative care for dementia patients. Overwhelmingly, respondents agreed or strongly agreed that dementia is a terminal illness (96%) and that palliative care is effective in dementia (98%). Programs providing palliative care for dementia patients were more likely to believe in palliative care’s effectiveness for this population (76% vs 44%).

DISCUSSION

This study reveals a significant and encouraging trend: nearly all hospice programs and a majority of hospice-affiliated palliative care programs now provide services for patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia. This represents a substantial increase from earlier surveys and suggests improved access to end-of-life care for this population. The near-universal recognition of dementia as a terminal illness among respondents, coupled with the belief in palliative care’s effectiveness, indicates a positive shift in provider attitudes.

However, despite this progress, significant barriers remain, particularly in non-hospice palliative care settings and earlier in the dementia trajectory. Lack of awareness among families and referring providers remains a major obstacle, hindering timely referrals and access to palliative care services. This finding underscores the need for targeted educational initiatives directed at both healthcare professionals and the public to enhance understanding of palliative care benefits in dementia, from diagnosis through bereavement. While education for palliative care staff was not highly rated as a barrier, it is crucial to ensure ongoing training to equip teams with specialized knowledge for dementia care.

The study highlights the intense palliative care needs of dementia patients and their families, particularly regarding caregiver burden, behavioral symptom management, and the need for comprehensive information and support throughout the disease course. The identified reimbursement challenges are critical, particularly for non-hospice palliative care. Patients often require home-based care and interdisciplinary support before meeting hospice eligibility criteria, creating a gap in service provision. The reliance on philanthropy by many palliative care programs underscores the inadequacy of current insurance models to meet these needs.

The study’s findings emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary teams and collaborative relationships with community organizations as key facilitators of successful palliative care for dementia. These elements should be prioritized in program development and policy initiatives. The interdisciplinary team model, a cornerstone of palliative care, is particularly well-suited to address the multifaceted needs of dementia patients and their families, offering holistic support encompassing physical, emotional, social, and spiritual domains.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The use of the NHPCO list may underrepresent non-hospice palliative care programs, especially newer programs. Data relied on self-reported information from program administrators, which may not fully reflect program characteristics or objective quality metrics. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators represent administrator opinions, potentially differing from those of direct care providers. The study’s program-level data preclude patient-level analyses of palliative care utilization. Response bias, particularly in the web-based survey, is a potential concern, although program characteristics of responders were generally consistent with national data.

Conclusion and Future Directions

In conclusion, palliative care provision for dementia has expanded significantly, particularly within hospice settings. However, substantial unmet needs persist, especially in non-hospice palliative care and earlier stages of dementia. Future efforts should prioritize:

- Education: Targeted education for families and referring providers to increase awareness of palliative care benefits in dementia from diagnosis to bereavement.

- Policy Reform: Reforming reimbursement structures to ensure coverage for interdisciplinary palliative care earlier in the disease course, when patients have significant needs but are not hospice-eligible.

- Caregiver Support: Strengthening support systems for caregivers of dementia patients, including respite care and resources to address caregiver burden.

- Interdisciplinary Care: Promoting and supporting interdisciplinary team-based palliative care models as the standard of care for dementia.

- Community Collaboration: Fostering collaborations between palliative care programs and community organizations to expand reach and resources.

By addressing these areas, we can significantly enhance the quality and accessibility of palliative care for individuals living with dementia and their families, ensuring comprehensive support throughout their journey from diagnosis to bereavement.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures for Greg A. Sachs: Consultant to CVS Caremark’s National Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee.

During the conduct of this study, SC was affiliated with NHPCO as the Vice President for Research and International Development, National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Foundation for Hospice in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This project was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Torke is supported by a Geriatrics Health Outcomes Research Scholars Award sponsored by the American Geriatrics Society and the John A. Hartford Foundation and a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG031323).

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

The study was presented in part at the Annual Meetings of the American Geriatrics Society, April 29–May 2, 2009, Chicago, IL and May 12–15, 2010, Orlando, FL and the Society of General Internal Medicine, May 13–16, 2009, Miami Beach, FL.

Author Contributions: All authors took significant part in all aspects of this manuscript.