INTRODUCTION

Dementia, encompassing a spectrum of progressive neurological conditions, poses a significant and growing health challenge in the UK. It’s a terminal illness profoundly impacting individuals and families, placing immense strain on society. 1 In 2015, approximately 850,000 individuals in the UK were estimated to be living with dementia, with projections exceeding 2 million by 2052. 2 Historically, underdiagnosis of dementia was widespread; as of 2009, it was considered “the norm,” with a staggering one-half to two-thirds of people with dementia in the UK lacking a formal diagnosis. 1,3 Recognizing this critical gap, the 2009 Dementia Strategy prioritized earlier diagnosis, leading to the introduction of several measures, notably two voluntary financial incentive schemes within primary care: the Directed Enhanced Service 18 (DES18) and the Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS). 4–7

DES18, active from April 2013 to March 2016, aimed to promote a proactive and timely approach to dementia diagnosis and support within primary care. 4–6 This involved identifying and assessing patients at risk of dementia, facilitating appropriate testing, and enhancing post-diagnosis support. Crucially, DES18 also focused on improving support for newly diagnosed individuals and their caregivers through referrals to specialist services and the provision of care plans and carer health checks.

Complementing DES18, the Dementia Identification Scheme (DIS) operated for six months, from October 2014 to March 2015. 7,8 DIS was designed to further encourage GP practices to proactively identify individuals with dementia. It encouraged collaboration between practices and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to develop relevant services and care pathways. Similar to DES18, DIS emphasized identifying at-risk patients, engaging with care and nursing homes to find symptomatic individuals, and offering dementia assessments to improve the accuracy of dementia registers within practices, ultimately aiming to enhance patient care.

While DES18 and DIS have been credited with increasing dementia diagnosis rates, 9 the broader, unintended consequences of these schemes, both positive and negative, remained largely unexplored. Financial incentive programs can inadvertently affect other facets of patient care, potentially diverting clinical and administrative resources from essential, non-incentivized services or conditions. 10 This study aimed to investigate the effects of DES18 and DIS on quality measures within the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) and on patient experience within primary care settings in the UK.

METHODOLOGY

To understand the potential broader impacts of primary care incentive schemes, a comprehensive literature review was undertaken to identify unintended consequences, both positive and negative, associated with DES18 and DIS. The search focused on UK-based studies of primary care incentive schemes published between 2006 and 2016. Databases including MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and HMIC were searched.

How This Study Adds Value

Previous evaluations of the DES18 and DIS schemes have confirmed their effectiveness in achieving their primary goal: increasing dementia diagnosis rates. However, a critical gap remained in understanding the wider impact of these schemes beyond their intended outcomes. This study addresses this gap by investigating the unintended consequences. The research reveals that while the schemes are linked to improved quality of care for dementia and other long-term conditions, certain aspects of patient experience may have been negatively affected. The study emphasizes the importance of using patient feedback, such as the GP Patient Survey, to identify and address any adverse effects arising from such incentive schemes.

The literature review, screening 509 records, identified 22 relevant studies. 10–31 None specifically examined the unintended consequences of DES18 or DIS. However, evidence from other incentive schemes revealed 12 potential unintended effects. These included changes in provider behaviors such as:

- Gaming: Inappropriate exception reporting to maximize incentive payments. 10,17,28

- Reduced clinical autonomy: Incentives potentially influencing clinical decision-making. 17,24,26,29

- Impact on internal motivation and provider professionalism: Potential shifts in intrinsic motivation due to external financial incentives. 17,26,10,24

Practice-level effects included:

Patient-related effects were identified as:

- Health inequalities: Incentives potentially exacerbating or mitigating existing health disparities. 10,11,15–20,22,30

- Loss of patient-centeredness: Care becoming less focused on individual patient needs and preferences. 13,14,18,19,21,25,27,30

- Impact on the doctor-patient relationship: Potential changes in the quality and nature of the doctor-patient interaction. 14,21,27

- Access to care: Changes in the ease and timeliness of accessing primary care services. 14

- Continuity of care: Effects on the consistency and ongoing nature of patient care with a preferred doctor. 13,14,18,19,22,28,30

- Spillover effects on quality of care: Influence on the quality of care for conditions and services outside the scope of the incentive schemes. 10,12,14,17,21,25,30,31

Data Collection

This study employed a retrospective cohort quantitative design, analyzing data from primary care practices in England. A balanced panel dataset was constructed, encompassing all practices over a 10-year period from 2006/2007 to 2015/2016. The data sources used to create the dependent and explanatory variables are detailed in Box 1.

Box 1. Datasets used for the analysis.

| Dataset | Reporting level | Year range | Type of variable(s) derived | Details of variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOF | GP practice | 2006/2007 to 2015/2016 | Dependent | Overall QOF achievement on clinical domain. Used to generate variables of the achievement of different QOF clinical indicators |

| Control | Practice-list size, percent of practice patients ≥65 years | |||

| GPPS (unweighted)a | GP practice | 2008/2009 to 2015/2016 | Dependent | Practice-level responses to each question in the survey Used to generate variables to investigate: patient-centred care, access to care, continuity of care, and the doctor–patient relationship |

| Dementia assessments data | GP practice | 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 | Policy | Used to identify participation in Directed Enhanced Services (DES18): Facilitating Timely Diagnosis and Support for People with Dementia |

| List of participation for DIS | GP practice | 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 | Policy | Used to identify participation in DIS |

| Dementia Assessment and Referral data collection | GP practice | 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 | Control | Used to construct ‘hospital effort’ indicator |

| HES | Patient | 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 | Control | Used to construct ‘hospital effort’ indicator |

| GMSb | GP practice | 2011/2012 to 2015/2016 | Control | Proportion of practice patients in different age and sex bands (≥65 years) used to derive expected dementia registers. GMS contract status |

| ADS | GP practice | 2006/2007 to 2015/2016 | Control | Numbers of practice patients in each LSOA. Used to generate practice- level weighted averages of rurality and deprivation |

| ONS: urban | LSOA | 2004 to 2011 | Control | Source of urban classifications. Combined with ADS to derive practice rurality measure. The 2004 data were used for missing values in 2011 |

| ONS: deprivation | LSOA | 2010 to 2015 | Control | Source of IMD classifications. Combined with ADS to derive practice deprivation measure. The 2010 data were used for missing values in 2015 |

| CCG code | GP practice | 2006/2007 to 2015/2016 | Control | Practice CCG code |

GPPS is a questionnaire sent to a sample of registered patients at each practice in England to gather data on various aspects of patient experience.32 GMS data collection methods changed in 2015–2016, resulting in missing data for approximately 15% of practices. ADS = Attribution Dataset. CCG = clinical commissioning group. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. GMS = General and Personal Medical Services dataset. GPPS = GP Patient Survey. HES = Hospital Episode Statistics. IMD = Index of Multiple Deprivation. LSOA = lower-layer super output area. ONS = Office for National Statistics. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

From the 12 potential unintended consequences identified in the literature review, five patient-focused measures were selected for analysis based on data availability. These domains, along with the specific measures used to evaluate the impacts of DES18 and DIS, are detailed in Box 2.

Box 2. Outcomes for the analysis of unintended consequences.

| Domain | Measure |

|---|---|

| 1. Schemes’ impacts on quality of care outside DES18 and DIS | Population achievement of all QOF clinical indicators excluding the dementia annual review and diagnosis indicator (a weighted measure of overall achievement of the QOF clinical domains [excluding dementia review and diagnosis indicator], with the maximum points for each indicator used as weights)Population achievement of the QOF dementia annual review indicator |

| 2. Patient-centred care | Mean percentage of responders answering ‘good’ or ‘very good’ to each part of the question:‘Last time you saw or spoke to a GP from your GP surgery: – How good was that GP at involving you in decisions about your care? – How good was your GP at listening to you? – How good was that GP at treating you with care and concern?’ |

| 3. Access to care | Percentage of responders answering ‘good’ or ‘very good’ to: ‘Last time you saw or spoke to a GP from your GP surgery, how good was that GP at giving you enough time?’ |

| 4. Continuity of care | Percentage of responders answering ‘almost always’ or ‘always’ to: ‘How often do you see (or speak to) the doctor you prefer to see?’ |

| 5. Doctor–patient relationship | Percentage of responders answering good or very good to: ‘Last time you saw or spoke to a GP from you GP surgery, how good were they at explaining tests and treatments?’Percentage of responders answering ‘yes, definitely’ to: ‘Did you have confidence and trust in the GP you saw or spoke to?’ |

DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Domain 1: Quality of care outside DES18 and DIS: Two measures from the QOF data were used to evaluate the impact on the quality of care beyond the specific dementia schemes. The QOF is a voluntary financial incentive program designed to improve the quality of primary care. 33,34 It incentivizes performance across 19 clinical areas and public health indicators. 33 Dementia care was included in the QOF in 2006. 35 Practices can ‘exception report’ patients, excluding them from specific indicators when calculating achievement for payment purposes. 33 This study used a ‘population achievement’ measure, including exception-reported patients in the denominator for both of the following measures:

- Composite QOF measure (excluding dementia): A measure of overall achievement across all clinical indicators in the QOF, excluding the two dementia-specific indicators (annual review and post-diagnostic tests for reversible dementia).

- QOF dementia annual review indicator: A measure of performance specifically on the annual dementia review for existing patients. 33,36

The composite QOF measure aimed to assess whether the dementia schemes impacted the quality of care for other long-term conditions. This impact could be negative, if resources were diverted from other areas, or positive, if better-organized practices performed well across all areas. The dementia annual review indicator assessed the schemes’ impact on care for existing dementia patients. The study did not assess the QOF indicator related to tests for reversible dementia in newly diagnosed patients, as improved post-diagnostic care was considered an intended positive outcome of the schemes.

Domains 2-5: Patient Experience: These domains focused on patient-centered care, access to care, continuity of care, and the doctor-patient relationship, measured using data from the GP Patient Survey (GPPS). Including these indicators allowed for the examination of whether the dementia incentive schemes had unintended consequences on broader patient experiences within primary care, which could be positive or negative depending on how practices managed their resources.

Explanatory Variables: The key explanatory variables were practice participation in DES18 and DIS. Practices were defined as DES18 participants in any year they reported data on dementia assessments, even if the number was zero, as this indicated engagement with the scheme. Data on DIS participation was provided by NHS England based on payment records collected by Local Area Teams.

Control Variables: To account for other factors influencing practice outcomes, the researchers controlled for various practice characteristics, including:

- Proportion of patients aged ≥65 years

- Practice list size

- Proportion of patients in the most deprived 20% small areas

- Proportion of patients in urban areas

- Number of full-time equivalent GPs per 1000 patients (in deciles)

- General and Personal Medical Services Contract status

- Hospital dementia screening activity (‘hospital effort’ indicator) 9,37–39

- Regional characteristics (CCG)

Data on deprivation and rurality were obtained from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and were attributed to practices as weighted averages based on patient distribution across lower-layer super output areas (LSOAs).

Statistical Analysis

A difference-in-differences (DID) design was used to model the impact of DES18 and DIS on unintended consequences. DID is a widely used method for evaluating policy impacts. 40 It was also used in a previous study to assess the intended effects of these schemes. 9 This method is suitable when data is available before and after the policy implementation for both participating (treatment) and non-participating (control) groups. A key assumption of DID is the ‘common trends’ assumption, which posits that treatment and control groups would have followed similar trends in the absence of the intervention. 40

Given the overlapping periods of DES18 and DIS, and the varying participation durations in DES18 over its three-year run, the model incorporated eight DES18 participation groups and two DIS groups, consistent with previous research. 9 A mixed-effects linear DID model, accommodating multiple periods and schemes, was employed. 9,41–43

RESULTS

National participation rates were high, with 98.5% of practices participating in DES18 and 76% in DIS. The study sample included 7079 practices. Table 1 shows the distribution of practice-years across different participation groups.

Table 1.

Practice participation in DES18 and DIS from 2006/2007 to 2015/2016

| Scheme and years of participation | Practice-years | % |

|---|---|---|

| DES18 | ||

| Years of participation: three | 56 200 | 79.39 |

| YYY | 56 200 | 79.39 |

| Years of participation: two | 11 130 | 15.72 |

| YYN | 1260 | 1.78 |

| YNY | 1370 | 1.94 |

| NYY | 8500 | 12.01 |

| Years of participation: one | 2400 | 3.39 |

| YNN | 440 | 0.62 |

| NYN | 680 | 0.96 |

| NNY | 1280 | 1.81 |

| No participation | 1060 | 1.50 |

| NNN | 1060 | 1.50 |

| Total | 70 790 | 100 |

| DIS | ||

| No | 16 970 | 23.97 |

| Yes | 53 820 | 76.03 |

| Total | 70 790 | 100 |

Table shows the size of the DES18 and DIS groups for the balanced panel. In total, 7090 practices contributed data for each year of the 10-year study period. Researchers identified different types of participants for the 3-year DES18, distinguishing practices into categories according to the number and order of participation years. For example, a practice that only participated in the first 2 years of DES18 (but not the third year) was categorised as YYN. DIS was only a 6-month scheme. DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. N = no. Y = yes.

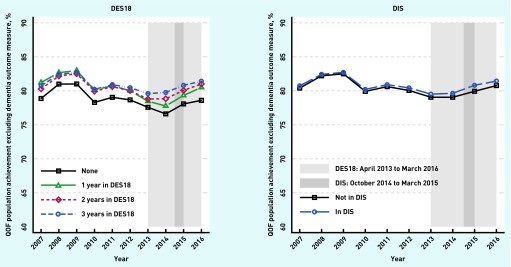

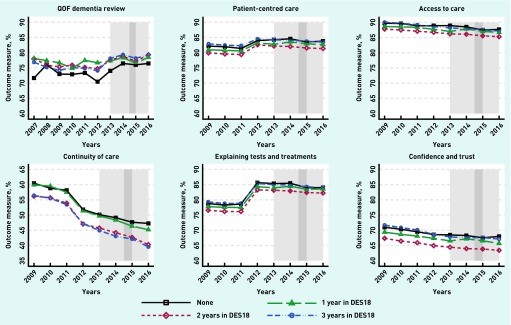

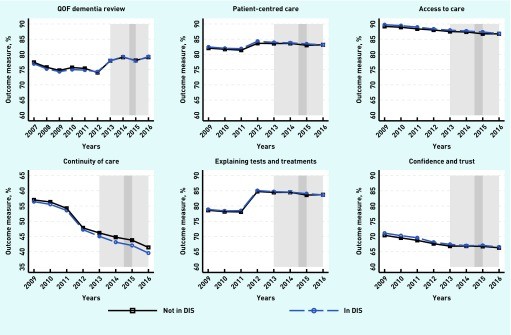

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the sample, and Table 3 summarizes the policy effects of DIS and DES18 on quality of care and patient experience. Analysis of the composite QOF measure (excluding dementia) is available upon request from the authors. Figures 1, 2, and 3 illustrate trends for the QOF clinical composite measure and patient experience measures. Formal pre-intervention trend tests confirmed parallel trends between control and treatment practices at a 0.1% significance level.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the estimation sample, N = 7079 practices

| Description | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population achievement of dementia review, weighted measure, % | 76.56 | 14.05 | 0 | 100.00 | 70 790 |

| Population achievement excluding dementia indicators, weighted measure, % | 80.76 | 4.56 | 0.05 | 99.79 | 70 790 |

| Patient-centred care from 2008/2009 to 2015/2016, % | 83.04 | 6.84 | 39.11 | 99.15 | 57 896 |

| Access to care from 2008/2009 to 2015/2016, % | 88.20 | 6.28 | 41.46 | 100.00 | 57 896 |

| Continuity of care from 2008/2009 to 2015/2016, % | 48.09 | 17.92 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 57 560 |

| Doctor–patient relationship 1 (explaining tests and treatments) from 2008/2009 to 2015/2016, % | 82.17 | 7.61 | 36.84 | 100.00 | 57 896 |

| Doctor–patient relationship 2 (confidence and trust in the GP) from 2008/2009 to 2015/2016, % | 68.26 | 10.73 | 19.05 | 98.29 | 57 896 |

| Practice patients ≥65 years, % | 16.13 | 5.68 | 0.17 | 47.99 | 70 790 |

| Practice list size, 1000s | 7.30 | 4.21 | 0.63 | 60.38 | 70 790 |

| Practice patients living in 20% most deprived areas, % | 23.01 | 26.14 | 0 | 99.65 | 70 790 |

| Practice patients living in urban areas, % | 82.57 | 32.54 | 0 | 100.00 | 70 790 |

| Full-time equivalent GPsa per 1000 patients, deciles | 0.57 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 8.98 | 70 790 |

| Hospital effortb from 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 | 86.10 | 17.02 | 0 | 100.00 | 21 237 |

| GMS contract | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 70 790 |

Excluding retainers/registrars. Hospital effort is assumed to be zero in the period 2006/2007 to 2012/2013. Unless otherwise stated, the variables cover 2006/07 to 2015/16. n = number of practice-years.

Table 3.

Results of the policy variables of DIS and DES18 on outcomes

| Domain measure | Quality of primary care | Doctor–patient relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Population achievement of all QOF indicators excluding dementia, coefficient (95% CI) | Population achievement of the QOF dementia annual review indicator, coefficient (95% CI) | Patient-centred care, coefficient (95% CI) |

| DES18 policy | 0.743a (0.490 to 0.996) | 1.302a (0.555 to 2.050) |

| DIS policy | 0.429a (0.209 to 0.648) | −0.01 (−0.749 to 0.729) |

| Within R2 | 0.116 | 0.025 |

| Between R2 | 0.141 | 0.142 |

| Overall R2 | 0.129 | 0.057 |

| Standard deviation of practice random effect | 2.976 | 5.706 |

| Intraclass correlation | 0.483 | 0.174 |

| Observations, practice-years | 70 790 | 70 790 |

| Practices, n | 7079 | 7079 |

0.1% significance level. 1% significance level. 5% significance level. DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Quality of Care Improvements

Practices participating in either DES18 or DIS demonstrated significantly higher overall quality of clinical care compared to non-participating practices. Specifically, DES18 participation was associated with a 0.743 percentage point increase in practice achievement, and DIS participation with a 0.429 percentage point increase in overall QOF performance (Table 3).

Furthermore, DES18 participation showed a statistically significant positive effect on the annual dementia review performance, increasing practice achievement by an average of 1.302 percentage points. DIS participation did not show a significant effect on this measure (Table 3).

Negative Impacts on Patient Experience

Despite improvements in quality of care metrics, the incentive schemes were linked to some negative aspects of patient experience. DES18 participation was associated with decreased scores in GPPS indicators for:

- Patient-centered care: Decreased by 0.525 percentage points (95% CI = -0.755 to -0.296).

- Access to care: Decreased by 0.364 percentage points (95% CI = -0.582 to -0.145).

- Explaining tests and treatments: Decreased by 0.371 percentage points (95% CI = -0.620 to -0.122).

- Confidence and trust in the GP: Decreased by 0.520 percentage points (95% CI = -0.837 to -0.202).

DES18 showed no significant impact on continuity of care. Conversely, DIS participation was associated with a negative impact on continuity of care, decreasing it by 0.663 percentage points (95% CI = -1.147 to -0.180). However, DIS was linked to improved patient experience in one aspect of the doctor-patient relationship: explaining tests and treatment, increasing it by 0.265 percentage points (95% CI = 0.006 to 0.525).

Figure 1.

Trends in the quality of primary care for long-term conditions in QOF (excluding dementia): variation by participation in the schemes. DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework. Light grey: DES18: April 2013 to March 2016. Dark grey: DIS: October 2014 to March 2015.

Figure 2.

Trends of outcomes for DES18 scheme. DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework. Light grey: DES18: April 2013 to March 2016. Dark grey: DIS: October 2014 to March 2015.

Figure 3.

Trends of outcomes for DIS scheme. DES18 = Directed Enhanced Service 18. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework. DIS = Dementia Identification Scheme. Light grey: DES18: April 2013 to March 2016. Dark grey: DIS: October 2014 to March 2015.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Findings

This study examining the unintended consequences of primary care incentive schemes for dementia diagnosis in the UK revealed a mix of effects. The schemes effectively improved QOF performance related to dementia reviews and also showed beneficial spillover effects on QOF performance in other clinical areas. This positive spillover might be attributed to practices using the additional funding from the schemes to enhance care across the board, or it could reflect the organizational capacity of practices that are adept at responding to incentive schemes. Regardless of the mechanism, the findings are encouraging as they show no detrimental impact on either dementia annual reviews or the quality of care for patients with other long-term conditions.

However, the study also highlighted negative consequences, particularly concerning patient experience. Analysis of GPPS indicators showed that DES18 was associated with negative effects on several aspects of patient experience. For DIS, the primary negative impact was on continuity of care. A plausible explanation for these negative effects is that practices, in focusing on dementia assessments to meet incentive targets, may have inadvertently reduced the time and resources available for other aspects of patient care, leading to the observed declines in patient experience metrics.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

A key strength of this study is that it addresses a significant gap in the evidence base by exploring the unintended consequences of incentive schemes aimed at improving dementia underdiagnosis. The study utilized comprehensive datasets covering nearly all general practices in England over a decade-long period, providing a robust foundation for analysis.

However, some limitations warrant consideration. GPPS data is derived from a sample of patients and may not fully represent the entire patient population’s experience. Furthermore, the study did not differentiate the impact on various patient subgroups, such as those with or without dementia, or their carers. It’s possible that certain patient groups experienced improvements in patient experience that were not captured in the aggregate data. Another limitation is the lack of control for other DES schemes, due to data unavailability.

Methodologically, observational studies like this are inherently limited. While randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for establishing causality, the DID approach is a strong alternative for evaluating non-experimental policy changes, especially in national-level schemes with varied participation over time and a long-term dataset. Although a range of covariates were included to control for practice and regional characteristics, and hospital effort, residual confounding cannot be entirely ruled out. Additionally, data limitations prevented the assessment of all potential unintended consequences identified in the literature review.

Comparison to Existing Research

Currently, no prior studies have specifically investigated the unintended consequences of DES18 or DIS. Research on the broader QOF and other local incentive schemes has shown mixed effects on the quality of care outside the incentivized areas. 10,12,14,31 While some studies found no significant impact on access to care or the doctor-patient relationship, 14 others have indicated a decline in continuity of care, 14,19 aligning with some findings of this study.

Implications for Policy and Future Research

This study suggests that while primary care incentive schemes for dementia diagnosis can improve diagnosis rates and overall quality metrics, they may also have small adverse effects on patient experience. Policymakers must consider this trade-off, balancing the value of improved dementia diagnosis against potential negative impacts on aspects of patient experience. Future evaluations of incentive schemes should routinely include assessments of both intended and unintended consequences. Utilizing patient feedback mechanisms like the GPPS can help practices proactively identify and mitigate any negative effects arising from these schemes.

Future research should explore potential gaming behaviors, such as inappropriate exception reporting, which was identified as a risk in the literature. Qualitative research could provide valuable insights into whether practices might have assessed patients inappropriately to maximize financial gains. The risk of misdiagnosis, particularly under pressure to increase diagnosis rates, also warrants further attention. Finally, variations in post-diagnosis support across different CCGs, potentially influenced by the varying impact of incentive schemes, highlight the need for policymakers to monitor future schemes and ensure adequate support for post-diagnosis care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to Kath Wright from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York for her assistance with the literature search. They also thank attendees at the Health Economics Study Group (winter 2018, City University), the project advisory group, and two anonymous referees for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (Policy Research Unit in the Economics of Health and Social Care Systems: reference 103/0001). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or other government bodies.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters